| JOURNAL 2017 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

The contribution made by Anglian settlers to place-names in the Dales can sometimes be under-estimated, especially when we dwell on words of Scandinavian origin which are associated with topographic features and with upland settlement in places such as Malham Moor. If we lower our gaze and concentrate on villages in the parishes of Burnsall and Linton, all situated in the valley, we soon notice how many of those names have characteristic Anglian elements: Appletreewick, Bordley, Grassington, Hartlington, Hebden, Kilnsey and Threshfield. It is true that we also have evidence of Scandinavian influence in Conistone, Cracoe, Thorpe and others but we can be in no doubt that the pattern of lowland settlement was in place long before Danes and Norwegians established themselves in the region. Those Anglian settlers may not have been the first settlers but they would certainly have had names for the distinctively-shaped hills which overlooked their communities.

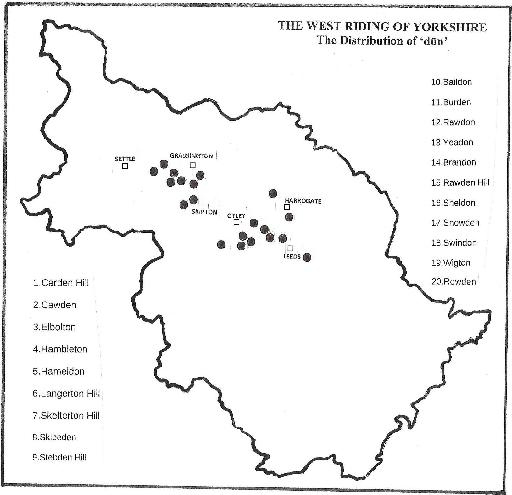

In this short essay our aim is to draw attention to a small number of place-names in that part of the Dales which seem likely to share the suffix dūn but which have previously been overlooked by scholars, partly because the available evidence is, for the most part, not of great antiquity but more particularly because the spellings are in general not conclusive: the nine names under consideration are Carden Hill, Cawden, Elbolton, Hambleton, Hameldon (Bordley), Langerton Hill, Skelterton Hill, Skibeden and Stebden Hill, all within the area that includes Skipton and Grassington, (see map), and all listed by Smith (1961): many of them have the prominent shape of rounded hills we associate with the term reef knoll. However, before we can examine those names in greater depth two preparatory points need to be made.

Reef knolls

The first point is to understand what reef knolls are and how they came to have such a characteristic shape: that takes us back to a period 350-360 million years ago when the area that was to become Britain lay close to the equator, far from the position it currently occupies. A warm and shallow sea slowly encroached on what would become the southern part of the Yorkshire Dales, in conditions similar to parts of the Caribbean now. Limy deposits lithified over time to become the Great Scar limestones and this land, known as the Askrigg Block, was buoyed up by a huge mass of low-density granite now known as the Wensleydale Granite.This block was slowly subsiding but the area to the south which had no granite beneath it was subsiding much more rapidly. Part of it became the Craven Basin and a greater thickness of deposits built up in the basin than on the block. The boundary between the Askrigg block and the region to the south was marked by a ‘series of tectonic faults – the Craven faults – best thought of as a fault zone or shatter belt with countless short faults’ [Johnson, 2008]. In particular, between the Askrigg Block and the Craven Basin, a major fault (the Mid-Craven fault) developed as a submarine feature. As sea levels fell the features we now call reef knolls began to form along its length.

It was a process that took place over a very long period. The slope was buffeted by waves from the deeper basins and these more-oxygenated waters were ideal for the growth of coral and algae which formed the basis of fringing reefs around 335 million years ago. The subsequent faulting and erosion which followed in the late Carboniferous or possibly early Permian period created the rounded hills which now form the Craven Reef Belt.

The place-name element dūn

The second point to establish is the history of dūn as a place-name element in Yorkshire. It is a word in use from the Old English period which has a wide distribution nationally, found most commonly as a suffix and meaning ‘hill’. A broader definition offered by Margaret Gelling is ‘hill, upland expanse’, although she made the point that the word could be used of very low hills: Hedon in east Yorkshire is only 20 to 30 feet above the Humber estuary [Gelling and Cole, 2000]. The distribution of dūn in the former West Riding is of real interest since there appear to be important districts where it is absent or its presence cannot be confirmed, including all the southern wapentakes of Agbrigg, Osgoldcross, Lower Strafforth, Staincross and Upper Strafforth; that is an area in which Barnsley, Doncaster, Huddersfield, Penistone, Sheffield and Wakefield offer a range of landscapes, from the Pennine moorlands in the west to the Hatfield Levels in the east.

Further north though there is one significant group of four names in Skyrack wapentake, all of them recorded in Domesday Book; that is Baildon, Burden (Harewood), Rawdon and Yeadon, ancient settlements in a tight-knit cluster north-west of Leeds. These were important localities at that time and they fall into a category which Gelling called ‘the application to ancient settlements of a new English name, the generic of which embraces both the habitation and the site’ [Gelling and Cole, 2000, 165]. Her point was that the Anglians who named such places were actually renaming them, since they were not the first people to occupy the sites. Close by but further to the north-east are seven additional names which were not listed in Domesday Book but are likely to share the same suffix: Brandon (1135-50), Rawden Hill (1138-50), Sheldon (1170-90), Snowden (c.1275), Swindon (12th C) and Wigton (1135-50). Finally, Rowden (1086) which is in the parish of Hampsthwaite completes the cluster. On the accompanying map these are the eleven locations in the area defined by Leeds, Harrogate and Otley.

Craven hills.

In contrast to that group of ancient settlements are the nine names listed in the introduction with possible dūn suffixes under consideration in the area north of Skipton quoted above. The evidence in these cases is generally very late although Skibeden was recorded in 1086 and Hameldon in Bordley (1283) and Cawden in Malham can be traced to the thirteenth century. In 1257 it was agreed between Fountains Abbey and Bolton Priory ‘that the walls raised by the Abbot and Convent in Caluedon ... remain in that state in which they were at Easter’. The Malham historian J.W. Morkill referred to Cawden as ‘a conspicuous feature of the landscape ... a conical hill’ in an area where lead had been mined in the nineteenth century [Morkill, 1933,6]. Arthur Raistrick described it ‘as a prominent detached hill ... a reef knoll’ [Raistrick, 1971, 68]. There is no hint of a settlement at Cawden for it was one of the township’s common pastures; a hill where calves could graze.This early spelling of Cawden persuaded Smith [1961] that it was another place-name with dūn as the suffix, unlike Elbolton Hill in Thorpe for which he had only the modern form and a date of 1849 from the tithe award. He made no suggestion as to what it might mean but a much earlier reference clearly points to another dūn suffix. In 1573 the hill was described in a dispute over grazing rights as ‘one great pasture close called Elbowdown’ [YASRS 39/45-6]. In those two respects it can therefore be compared with Cawden and, more interestingly, it was also a distinctively-shaped reef knoll where lead had been mined (Raistrick and Jennings, 1965, 57).

For the names Skelterton Hill and Stebden Hill, both of which are reef knolls, no early examples have yet been noted but the suffixes have spellings which allow us to compare them with Elbolton and Cawden. A similar name near by is Carden Hill in Cracoe which Smith interpreted as ‘marshy valley’, taking the suffix to be ‘den’, but it is likely to be another dūn since Raistrick had Cardons as his first reference in 1722 [YASRS 6/89] and it was recorded as Cardon in a Cracoe title deed of 1588 [YAS MD247]. Finally, in 1558, when William Blande was buried at Burnsall he was said to be of Langardon which probably refers to Langerton Hill in Hartlington rather than Langerton near Thorpe [YASRS 14/17]. A point worth noting is that several of these names were referred to as hills later in their history.

In general, of course, and as a matter of principle, only place-names for which there is very early consistent material can be offered as evidence for the use of a particular element, but these hills are very distinctive topographical features so it is surely worthwhile to raise the question of how they might have been named. The lack of early evidence is because they were not settlement sites and were not for the most part on significant boundaries. Nevertheless, additional spellings may eventually be noted in which case the topic can then be re-examined. Our suggestion at present is that they may once all have had dūn as the suffix, and in support of that it is worth noting that English Place-Name Elements [EPNE138] recognizes that dūn ‘as a final element ... is often confused in modern spellings with denu and tūn’. That seems certain to have happened in the cases of Carden, Cawden, Elbolton and Langerton and it would not be surprising if it happened also to Skelterton and Stebden. The Domesday spelling of Skibeden suggests that it posed a problem to scribes even then.

A note on Skibeden

Skibeden is treated in this article as a ‘dūn’ – ‘the common early form’ of the name in the words of Smith [1961, 6/73]. He was unsure about this origin and it should certainly be considered as doubtful, since the Domesday spellings are Scipeden and Schibeden, both of which point to ‘denu’, meaning valley, as the final element. However, typical twelfth-century spellings are Skybdune and Skybedon and these appear to have persuaded Smith that it was likely to be a hill-name. Since the two types of spelling persist through much of the place-name’s subsequent history the matter remains unresolved.The topographic evidence favours ‘dūn’, with the present sites of High and Low Skibeden on the shoulder of the hill to the east. However, a larger hill to the north-west is Haw Bank, a limestone hill. It is not impossible that Haw Bank was the original ‘sheep-hill’- and that it was renamed by Scandinavian settlers, just as they influenced the pronunciation of the first element in both Skipton and Skibeden. Other hills in the region derive from Scandinavian ‘haugr’ and the early foundation of a settlement at Skibeden may have contributed to Haw Bank losing its original name.

In conclusion, attention should perhaps be drawn to the fact that some philologists have suggested that dūn may actually have a Celtic origin, and the arguments for and against that are on record. Whether or not that is the case it is likely that the names of reef knolls and other prominent hills in that part of Craven date back to well before the ninth century.

Acknowledgement

Thanks to Dr. David Johnson for his refreshing look at the Carboniferous (Johnson, 2008).

References

- EPNE 1956. English Place-Name Elements, English Place-Name Society publications, xxv

- Gelling, M. and Cole, A., 2000. Reprinted 2014, The Landscape of Place-names, Shaun Tyas, 165

- Johnson, D., 2008. Ingleborough, Landscape and History, Carnegie Publishing.

- YAS MD247 Deeds relating to Kilnsey and neighbouring townships in the Dales, Collection held by the Yorkshire Archaeological Society, University of Leeds Brotherton Library, Leeds.

- Morkill, J.W., 1933. Reprinted 2005. The Parish of Kirkby Malhamdale, 6

- Raistrick, A. and Jennings, B., 1965. Revised 1983. A History of Lead Mining in the Pennines, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, 57

- Raistrick, A., 1971. Malham and Malham Moor, Dalesman Publishing Company, 68

- Smith, A.H., 1961. Place-names of the West Riding of Yorkshire, Cambridge University Press.

The ‘dūns’ shown on the map can be found in the relevant volume:-

| Group 1 | Group 2 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carden Hill | vol.6 p.89 | Baildon | vol.4 p.158 | |

| Cawden | vol.6 p.135 | Burden | vol.4 p.185 | |

| Elbolton | vol 6 p.96 | Rawdon | vol.4 p.152 | |

| Hambleton | vol.6 p.66 | Yeadon | vol.4 p.155 | |

| Hameldon | vol.6 p.83 | Brandon | vol.4 p.187 | |

| Langerton Hill | vol 6 p.91 | Rawden Hill | vol.4 p.186 | |

| Skelterton Hill | vol.6 p.89 | Sheldon | vol.4 p.51 | |

| Skibeden | vol 6 p.73 | Snowden | vol.5 p.61 | |

| Stebden Hill | vol. 6 p.96 | Swindon | vol.5 p.43 | |

| Wigton | vol.4 p.187 | |||

| Rowden | vol.5 p.134 | |||

YASRS Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series, (vol. no./page).

Bibliography Aitkenhead, et. al., 2002. British Regional Geology: the Pennines and adjacent areas (Fourth edition), British Geological Survey, Nottingham. Ensom, P., 2009. Yorkshire Geology, Dovecote Press Waltham, T., 2007. The Yorkshire Dales, Landscape and Geology, Crowood Press.

Waltham, T. and Lowe, D. (eds) 2013. Caves and Karst of the Yorkshire Dales, British Cave Research Association.