| JOURNAL 2017 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

Introduction

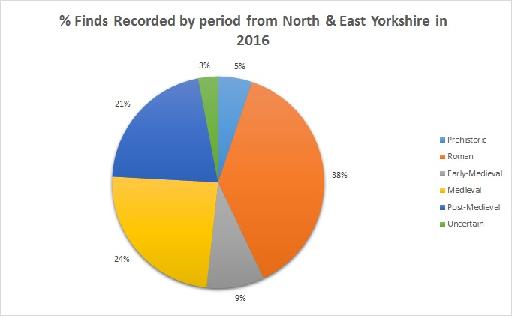

2016 was another productive year for the Portable Antiquities Scheme (PAS) in North and East Yorkshire. Over 4000 new records of archaeological objects were created, containing over 5000 individual objects when hoards and assemblages are taken in to account. The PAS is a national initiative with the aim of identifying and recording archaeological artefacts found by members of the public. The Scheme has a network of 37 Finds Liaison Officers (FLOs) who work to record these finds. The majority of these artefacts are discovered by metal detectorists, and FLOs work closely with metal detecting clubs to ensure as accurate a record as possible is created. An increasing number of finds also come from members of the public who make their discoveries through activities such as gardening or dog walking.Records created by the PAS are made publicly available via our online database (www.finds.org.uk/database) so that the data can be used by anyone who has an interest in the archaeology of England and Wales. With over 1 million objects recorded, the PAS database represents one of the largest and most comprehensive sets of archaeological information. All periods are well represented within the North and East Yorkshire data set (Fig. 1).

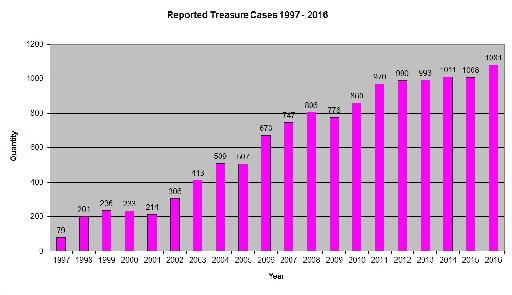

The PAS is also responsible for the administration of the Treasure Act 1996 with FLOs advising finders of their legal obligations, providing advice on the process and writing reports for Coroners on Treasure finds. The number of reported Treasure cases has increased significantly since the Scheme’s inception from just 79 cases in 1997 to 1081 in 2016 (Fig. 2). Prior to the Treasure Act, only around 25 finds per year were declared to be Treasure Trove. The increase has meant that far more significant material has been acquired by local museums, where it can be enjoyed by all.

A number of significant and exceptional finds were recorded from North and East Yorkshire in 2016. Others are more mundane, but illustrate important aspects of life in the past, such as trade or manufacture. Others I like simply because they were unusual or quirky.

Prehistoric Finds (c. 500,000 BC - AD 42)

The prehistoric period begins with the emergence of the human species around five million years ago, and ends with the arrival of the Romans and the advent of the written word. Only 5% of the material recorded with PAS is from this period but the wide range of flint tools produced are clearly represented. One of the most distinctive and elaborate of these are the barbed and tanged arrowheads of the Bronze Age. Figure 3 is such an example which was created by finely shaping struck flakes using a technique known as pressure-flaking which involves involved removing small flakes by pushing them off with a tool made of a softer material. Bone or antler were used in the Mesolithic and Neolithic periods, but copper was used in the Bronze Age. The central tang was used to secure the arrowhead to its shaft while the flanking barbs prevented the arrow being dislodged as an animal bolted. If the arrow was removed, the barbs caused a vicious wound, ensuring the hunters did not have far to track their prey.Skill in metalworking developed throughout the Bronze and Iron Ages with the technique of making iron objects being imported from the Continent. Despite this, copper-alloy objects are still the most common from the Iron Age. Figure 4 shows one of the more unusual finds from this period. Comprising an openwork petal-style design with a broken suspension lug projecting from the reverse this is known as a fob dangler. The function of these objects is poorly understood. They may have been hung from items of equipment or personal apparel, or served as harness decoration. They are traditionally assigned to the late Iron Age to early Roman transition based on the triskele motif decoration of most examples. However, the pointed oval ‘petal’ motif employed on this fob is one that continued in use well into the Roman period.

Brooches are common finds from most periods but the copper-alloy Iron Age example shown in Figure 5 is comparatively rare and, as such, was an exciting find. Similar brooches have been found in the Arras Culture burials of the East Riding of Yorkshire with the hollowed areas containing glass beads or coral. The Queen’s Barrow Brooch, now in the Yorkshire Museum, is one such example and another was recently found at Pocklington, East Yorkshire.

Roman Finds (AD 42 - 410)

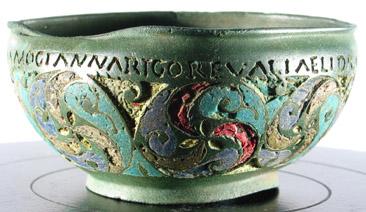

Roman finds are by far the most common recorded with the scheme, reflecting the density of settlement and importance of metal objects in the period. They typically make up more than 50% of all finds reported and are found in every part of the region. Nonetheless, interesting and unusual objects from the period continue to be unearthed such as this enamelled patera. This type of object is a form of vessel comprising a long handle and bowl. The example in Figure 7 is decorated on the outer surface with three parallel rows of evenly spaced recessed square cells, filled with repeating yellow, red, blue and green enamel. The handle is also highly decorated, with an engraved inscription which reads: VTERE FELIX (use in happiness). The letters retain enamel in alternating red and blue. “VTERE FELIX” is an inscription used for the invocation of good luck and featured on a variety of Roman object types. Two finger rings bearing the “VTERE FELIX” inscriptions have also been recorded with PAS: DOR-8F5E8E from Gussage St Michael, Dorset and BH-C3A8E7 from Hockliffe, Bedfordshire. LIN-C355C3 from North Kesteven, Lincolnshire is a brooch fragment with the same inscription.Patera could perform a number of functions. Some were shallow, circular vessels, used to contain liquids for ceremonial, sacrificial or domestic purposes. Very elaborate vessels such as the Staffordshire Pan (Figure 8), which lists four forts located at the western end of Hadrian’s Wall were non-functional and are likely to have been souvenirs or commemorative issues awarded to an individual. It is likely that this example from Yorkshire falls into the category of ceremonial or commemorative patera due to its highly decorative style. Simpler forms were carried by Roman soldiers as part of their standard kit and used as general cooking and eating utensils, but these examples tended to have pronounced concentric rings on the base which may have aided heating and the handles had perforations at the terminal end for suspension. An example of one of these on the PAS database is Figure 9.

Enamel decoration is a common theme on many of the objects recorded by the PAS as the technique became prevalent in the Roman period. Figure 10 shows a particularly fine example of an enamelled button and loop fastener. It has a circular head with a quartered circular enamelled motif set within a circular recess at its centre. Such objects are believed to be a product of the northern school of enamellers of the second century A.D with red and yellow being the predominant colours. White, green and blue enamels also feature on many objects with a flower-petal design being favoured.

The number of recorded examples of button and loop fasteners has increased significantly through the PAS, and previously unrecorded variants known as ‘double-headed’ types (such as Figure 11) have been identified. Few double-headed examples have been published, and only twenty-two have been recorded with the PAS. Almost all of these are from northern counties, and one was found in the Scottish Traprain Law Hoard, which is thought to be a haul looted from Yorkshire by Pictish raiders. The relatively restricted distribution of these objects may reflect an aspect of regional identity specific to the North.

Roman coins are the most commonly recorded object of all representing over 21% of the total number of finds recorded by PAS. Figure 12 shows a silver denarius of Septimius Severus dating to AD 202 and minted in Rome. It is particularly significant due to Severus’s ties with the city of York. Septimius Severus used York as a base from which to launch his military campaigns in Scotland. His expeditions were unsuccessful and, in AD 211, he fell ill and died in York.

Early-Medieval Finds (AD 410 - 1066)

Despite representing just 9% of the total number of finds recorded with PAS objects from this period are many and varied, displaying the different decorative styles of distinct cultures. One of the most common types of Early-Medieval artefact recorded with PAS are strap ends. These were used to prevent straps from fraying and also to weigh down garments so they hung more attractively. The example in Figure 13, though worn, represents a common zoomorphic (animal headed) theme which can be seen in numerous artefacts pf the period. These objects were made with numerous designs though the most common feature zoomorphic terminals in the form of a forward-facing animal head with rounded eyes and a stub-nosed snout at the closed end. This example is also decorated with two rectangular panels on the main plate, one of which contains inlaid silver wire forming a large S-shaped motif with scrolled terminals. Late Anglo-Saxon and Viking strap ends have been classified into several types dating broadly from the 9th century. Type 5 strap ends are the most narrowly distributed of the types with the majority found in Suffolk and Norfolk, suggesting an East Anglian origin. Outliers are thought to reflect trading networks along the eastern seaboard. A more unusual object is the gilt copper-alloy mount in Figure 14 in the form of a horned human head. Images of horn-helmeted figures usually appear on full figures, often in pairs and/or performing some kind of ceremonial dance with weapons. They are common in Germanic areas from the 7th century until the early Viking period. Such objects are thought to be connected to the cult of Woden, representing Woden himself, who was the principal Anglo-Saxon/Germanic god, corresponding to the Norse Odin.Gold coins are always exciting finds as so few are discovered. Figure 15 shows a particularly significant example of a new type. It is a shilling (also known as a thrymsa) minted in York which is distinctly different from the majority of other coins of the same period. Only nineteen examples of this York group of gold shillings are known. They were struck in the early seventh century, and represent the first coinage ever made in York. Until recently, their attribution to a mint in York was uncertain, but recent finds, which show a clear Yorkshire focus, have made this very likely. The obverse (front) image of a standing figure holding two crosses is likely to be a religious figure, possibly York’s bishop. The coin is also an indicator of high status, being used not for simple monetary exchange, but rather as a status symbol and for gift-giving among the elite.

Medieval Finds (AD 1066 - 1500)

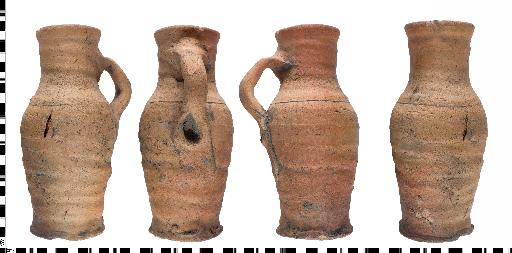

While the majority of objects recorded with PAS are made of metal, objects of other material, such as ceramic, are also recorded. Incomplete and fragmentary objects are also common so a complete ceramic vessel was a refreshing change. The object in Figure 16 was discovered beneath the foundation of a wall during reconstruction of a barn. The fabric and form are consistent with the Humber Ware industry, of which small drinking vessels are one of the best known products. These vessels could however have various common uses as drinking vessels, urinals, and even coin hoard containers! The irregular base of many examples meant they must have been unstable. This base of this vessel is not parallel with the top so it stands at a slight acute angle, but is stable. The findspot of this vessel suggests it may have acted as a foundation deposit, serving an apotropaic (evil- preventing) function.Religion was a key element of the medieval mindset and many objects with religious connotations are recorded with the PAS every year. Papal Bullae would have been attached to documents issued the Pope, acting as a seal and means of authentication. The example in Figure 17 was issued under Pope Benedict XI who was Pope from 22nd October AD 1303 to his death on 7th July, AD 1304. The obverse is stamped with the faces of the saints Peter and Paul within a border of raised pellets. Above the heads, the saints’ abbreviations are visible with ‘SPA’ for St. Paul to the left and ‘SPE’ for St. Peter to the right. The reverse bears the Pope’s name: BENE//DICTVS//.PP .XI. The ‘PP’ stands for ‘pastor pastorum’ which translates as ‘shepherd of the shepherds’.

During the 15th and 16th centuries the English economy experienced a serious shortage of English-struck halfpennies. In order to fill this gap people began using foreign coinage such as the soldino, meaning ‘little shilling’, which weighed slightly less than the English halfpenny, and entered into English currency through Venetian traders. Figure 18 is one such example of a silver Venetian soldino issued under Doge Michael Steno which dates to AD 1400 - 1413. The obverse (front) shows the Doge kneeling in prayer and the reverse depicts the winged lion of St Mark, the symbol of Venice, holding a book of gospels.

Post-Medieval Finds (AD 1500 - 1900)

The Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw increased mechanisation and mass-production. Consequently, the PAS is selective in recording finds from this period and generally focuses on those artefacts that are of particular historical or social interest. Finger rings bearing inscriptions are referred to as ‘posy’ rings, from the French ‘poésie’ or poetry and are common finds from the Post-Medieval period. They provide a detailed view into the lives of individuals with the inscription generally found on the interior of the ring, hidden to everyone except the wearer. The example in Figure 19 is inscribed with sentimental text reading, ‘I LYKE MI CHOVS TO WEL TO CHANG’ (’I Like My Choice Too Well to Change’). The practice of giving rings engraved with mottoes at betrothals or weddings was common in England from the sixteenth century onwards, and continued until the late eighteenth century. Posy rings could also be given on other occasions as a token of friendship or loyalty, and could contain religious or memorial inscriptions. Most of the sentimental mottoes were taken from popular literature of the time.Coin finds from this period are also extremely common but an interesting feature of Post-Medieval currency appears in the form of copper alloy trade tokens. Figure 20 shows a halfpenny token issued by Michael Pennocke, a wine merchant or vintner, from New Malton and is dated AD 1666. Trade tokens such as this were issued between 1648 and 1673 at a time when there was little low denomination coinage being issued by the crown. As a result traders and business proprietors began issuing tokens as an alternate coinage with equivalent denominations of a farthing, half penny or penny. Such trade tokens rarely travel far from their place of issue and provide a wonderful insight to the trade practices of the time. On 16 August AD 1672, a proclamation by the Crown ordered the minting of trade tokens to cease. This was largely ignored and two further proclamations were issued in subsequent years, the latter finally being effective.

Flint, the first material described above, enjoyed an important use once again in this period in the realms of weaponry. The flintlock musket was introduced in the middle of the 16th century and became the main regulation firearm for the British Army during the reign of William III. Knapped flint such as that in Figure 21 was used within the musket mechanism to produce a spark and could last between twenty and twenty-five shots before it had to be replaced. A similar example (Figure 22) has also been recorded with PAS. This record states that there is no documentary evidence for when or where sparks from flint were first used to fire gunpowder, but flintlock guns were being used in France from about 1600. There is a written record of an order received by London gunsmiths in 1661 to provide 15,000 ‘flintstones cutt’ for the garrisons in Tangier and Ireland. This gunflint may have been associated with the local activity during the Civil War, but they continued being used throughout the 19th century, especially during the Napoleonic Wars.

Concluding Thoughts

Artefacts recorded with the PAS are many and varied, and their distribution is of great importance to archaeologists and the public alike, allowing everyone to better understand the landscape, as well as how people lived and worked in the past. The PAS provides a means to create a cohesive, publically available data set which would otherwise be lost. This has numerous benefits, from the ability to identify new archaeological sites through analysis of assemblages to the capacity to show patterns in finds distribution across the country. Additionally, new types of artefact come to light. Therefore, through the careful recording and plotting of findspots to a minimum six figure grid reference, every object on the PAS database has the potential for use as a source to further our knowledge of the past.The author, Rebecca Griffiths, is Finds Liaison Officer for North and East Yorkshire If you would like to learn more about these or any other finds recorded with the Portable Antiquities Scheme please visit our website at www.finds.org.uk.

A new book entitled ‘50 Finds from Yorkshire: Objects from the Portable Antiquities Scheme’ can now be purchased from Amberley Publishing (https://www.amberley-books.com/50-finds-fromyorkshire.html).

Fig.1: Percentage of finds recorded by period from North & East Yorkshire

Fig.2: Number of reported Treasure cases 1997 - 2016

Fig.3: YORYM-942674 - A Bronze Age barbed and tanged arrowhead

Fig 4: YORYM-30130C - An Iron Age oddity

Fig.5: YORYM-ACFE1D - A copper-alloy Iron Age brooch

Fig.6: YORYM : 1948.907 - Image courtesy of York Museums Trust : http://yorkmuseumstrust.org.uk :: CC BY-SA 4.0

Fig 7: YORYM-20B68C - A highly decorated patera

Fig 8: WMID-3FE965 - The Staffordshire Pan

Fig 9: NCL-335745- A functional patera with concentric rings on its base

Fig 10: YORYM-EA7D62 - An enamelled button and loop fastener with circular head

Fig 11: YORYM-AC7061- A double headed button and loop fastener

Fig.12: YORYM-5808FB - A silver denarius of Septimius Severus

Fig.13: YORYM-DC87EC - Copper-alloy strap end

Fig.14: YORYM-FAE4AF - A gilt copper-alloy mount

Fig.15: YORYM-504283 - A gold York Group shilling

Fig.16: YORYM-BFDCBB - A complete medieval ceramic vessel

Fig.17: YORYM-A73B69 - Lead-alloy papal bulla

Fig.18: YORYM-D0A453 - A silver Venetian soldino of Doge Michael Steno

Fig.19: YORYM-C2732F - A gold posy finger ring

Fig.20: YORYM-0E5E56 - A copper-alloy trade token

Fig.21: YORYM-4BE22E - A gunflint with lead-alloy holder

Fig.22: WILT-0B6F58 - A gunflint with lead-alloy holder

Fig.23