| JOURNAL 2018 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

Victorian novels are not everyone’s choice of reading matter, but when you find one mentioned in Brayshaw and Robinson’s A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick [1932], interest is aroused. The book in question is Wooers and Winners, or, Under the Scars. A Yorkshire story by Mrs. George Linnĉus Banks. It was published as a three-volume novel in 1880, having the previous year been serialised as Under the Scars in three northern provincial weeklies.

The story spans the period 1830 - 1847, revolving around a young man named Allan Earnshaw (aged fifteen years old at the start), his sister Edith (then thirteen) and their step-father Archibald Thorpe and five year-old step-sister Dora who all live at the ancestral Earnshaw home, Ivy Fold, adjacent to St. Alkald’s (sic) Church in Giggleswick. Allan is an ex-Giggleswick Grammar School boy, now apprenticed in the counting-house of a Leeds merchant, while Edith is still at the local school run by Mrs. Esther Cragg, formerly of Hornby, her daughter Elizabeth and niece Miss Ann Vasey. This school at Well Bank, next to the Vicarage, also serves as a boarding house for the Grammar School. Allan, Edith and Dora have financial prospects through a rich great-aunt in Skipton. Allan and Edith’s step-father is kindly to them but other-worldly, engrossed in his local geological, botanical and archaeological interests. One strand of the tale is provided by a schoolboy jape where an unknown boy dresses up as a ghost. The frightening effect of this may have had the effect of hastening the death of Allan, Edith’s and Dora’s mother and leads to subsequent difficulties and financial implications. Another story-line involves two young men; one, Martin Pickersgill, an upright and handsome youth who was sent to the Grammar School from a West Indian slave-owning indigo plantation background and is in danger of being defrauded of his plantation and South Yorkshire colliery inheritance, and the other a fellow pupil, Jasper Ellis, always with an eye to self pecuniary advancement and not above duplicity and wrong-doing to achieve it. Both pay court to Edith for their different reasons. Mysteries surround wills affecting Pickersgill and the Earnshaws.

All these plot elements are set against the backdrop of Giggleswick and its inhabitants, the staff and pupils of the Grammar School, the houses where the boys lived, the Craven countryside, geology, and local landscape features such as the Ebbing-and-Flowing Well, together with the characters’ connections in Settle, Skipton, Leeds and the South Yorkshire coalfield near Barnsley. Background events include the Leeds election of 1832 and the cholera epidemic there in the same year, the Mechanics’ Institute movement, the rise and fall of railway investment fever, the emancipation of West Indian slaves in 1833-4, and the improvement of conditions in the coalfields following the Mines Act of 1842. In the end, of course, everybody, good or bad, gets his or her just deserts. There are a number of vividly drawn lesser dramatis personĉ - so many, in fact, that in progressing through the book any reader with any sort of acquaintanceship with the history of these areas and of the times will have become aware not only of the authenticity of the settings described, but also that many of the novel’s characters were in fact real people.

It is very clear that the author knew the area extremely well and that she had intimate knowledge of people who lived there, particularly in Giggleswick, at that time. But how could this be, when the novel’s events took place forty to fifty years before she published the story? Born Isabella Varley on 25 March 1821 in Manchester, she would, after all, have been only nine years old in 1830. Some investigation seemed called for.

The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography and also a biography Mrs. G. Linnĉus Banks by E.L. Burney [1969] give us the background to her life. Isabella Varley was the daughter of James Varley, a chemist, and Amelia (née Daniels). Her Daniels relations were in the drapery and related trades and Isabella’s novels show a close interest in the dress of her characters. Her Varley grandfather, another James, had discovered the use of chloride of lime for bleaching cotton. Well-educated, she first had published a poem at the age of sixteen. For the next ten years she kept a school at Cheetham, Manchester, and became actively interested in the Anti-Corn Law League and later women’s suffrage. She was also very interested in British traditional literature and published volumes of poetry, as well as being skilled in needlework and knitting, producing a monthly series of fancy-work patterns over a period of some forty-five years. In 1846 she married George Linnĉus Banks, a Birmingham journalist and poet, who became editor of a number of provincial papers over the years, including The Harrowgate Advertiser between 1848 and 1852. Isabella travelled with him to his various postings, absorbing background material - history, landscape, characters, dialect - which she could later draw on. They were both particularly keen on the Mechanics’ Institute movement. However, her husband had an increasingly expensive drink problem, so despite poor health herself and giving birth to eight children (five pre-deceased her), at the age of forty-three she started to write novels to help support the family. The settings were places she now knew - Yorkshire, Lancashire, Durham, Birmingham and of course Manchester which was the scene of The Manchester Man [1876], her most famous work, concerning the story and characters surrounding the Peterloo Massacre of 1819. She also provided numerous contributions to the Notes and Queries pages of the Manchester City News. She came to know many literary lights of the day such as Charles Dickens, Elizabeth Gaskell and Victor Hugo.

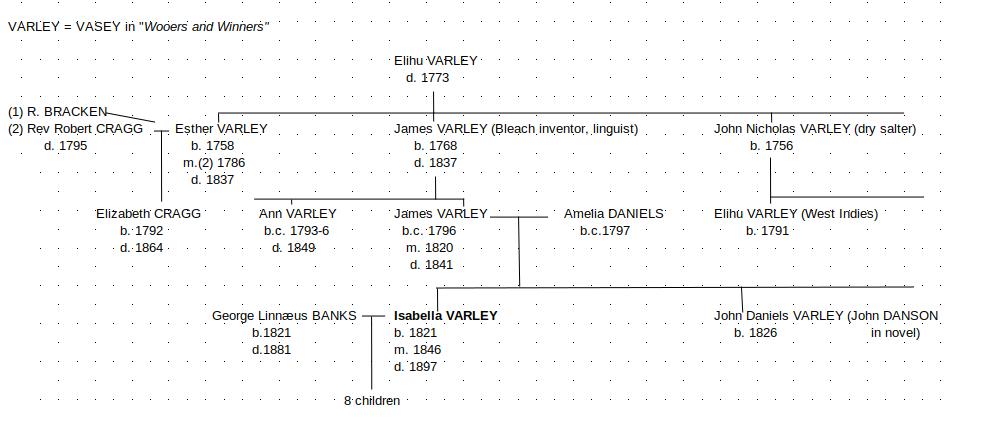

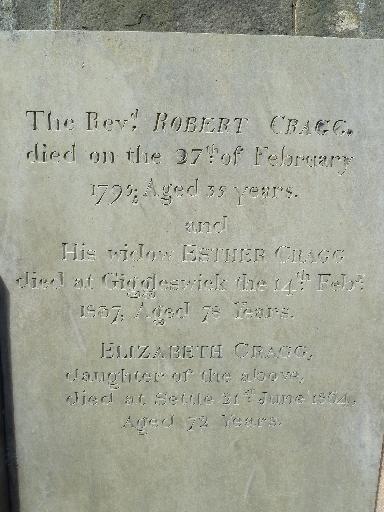

Besides gaining inspiration from the surroundings in which she had found herself during the various periods of her life, she also absorbed and used material from her own family history. The Varleys came from Hornby in Lancashire. Her great grandfather was Elihu Varley, and he had several children including Esther, born c. 1759, John Nicholas, born c. 1761 and James, his youngest son and Isabella’s grandfather mentioned above, born c. 1769 (Figure 1). This latter man was an interesting character. Besides inventing bleaching powder, he had travelled widely in Europe, had penetrated a Turkish harem in disguise, had been present at the storming of the Bastille and spoke fourteen languages. Some of these aspects of his life, and others, are hinted at in the character of James Vasey described in the book. Esther married twice, firstly a Mr. R. Bracken, and secondly the Rev. Robert Cragg by whom she had a daughter, Elizabeth. John Nicholas Varley’s children included another Elihu (the fictional Elihu Vasey) who became a West Indian planter, and James’ children included Isabella’s father James and presumably also a daughter Ann, assuming the book’s fictional relationship to be true. Isabella herself had several siblings, one of whom was a brother John Daniels Varley who was sent to Giggleswick School, boarding with his great-aunt Esther, in 1833. It is important to note these family names as many appear in Wooers and Winners either as they are, or under the thinnest of disguises. In the novel their real histories and relationships are described very accurately. Although the Varley name appears as Vasey in the book, Esther and Elizabeth Cragg appear under their own names. The real Esther Cragg died in Giggleswick in 1837, and Elizabeth in Settle in 1864, and both are buried in St. Margaret’s churchyard, Hornby, where also may be seen other stones commemorating Elihu Varley, Isabella’s great grandfather, d. 1773, and James Varley, Esther’s brother and Isabella’s grandfather who died in Giggleswick in 1837 shortly after his sister (Figure 2). Ann Varley died and was buried in Giggleswick in January 1849. Isabella’s brother John Daniels Varley appears in the novel as John Danson, a Hornby surname also to be seen on a tombstone in St. Margaret’s churchyard. The fictional hero’s surname, Earnshaw, was that of an early family friend. The sexton in the story is named Bracken, the surname of the real Esther’s first husband. A number of subsidiary characters, such as Dr. Thomas Dixon Burrow and John Tatham, the botanising Quaker shopkeeper of Settle, Parson Clapham and his eccentric son Thomas, and from Giggleswick School the Revs. Rowland Ingram (headmaster) and John Howson (usher), appear in the book under their own names. The reality of all these people, if proof is needed, can be confirmed by historical writings or reference to censuses online and family history websites, although their characters as portrayed in the novel may only have been very distantly remembered or learnt from family reminiscence.

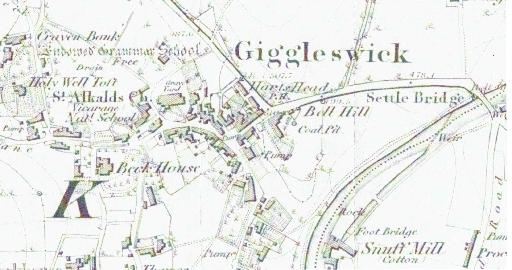

Archibald Thorpe is an interesting character who, according to Adelene Buckland in her book Novel Science [2013], epitomises the geologists and other similar scientists of the period who were obsessive to the point of being neglectful of other responsibilities. Isabella writes ‘Mr. Thorpe, who had more knowledge of plants and stones than of humanity...’. Others of her books have similar characters. In the novel she has Thorpe, together with Martin Pickersgill, discovering the cave which became known as Victoria Cave. In reality, of course, the cave was discovered in 1837 by Michael Horner and Joseph Jackson. Various reports followed, culminating in William Boyd Dawkins’ account in Cave Hunting [1874], which Isabella very probably had read. Because so much of Isabella’s time had been spent in the newspaper world, she would have been fully aware of the value of past newspaper files for information about wider events such as the Leeds election of December 1832, the period, the effects and personalities of railway mania, the abolition of slavery and the social conditions in coal-mining communities. Isabella’s own teenage urge to write is mirrored in her heroine Edith’s similar experience, both having early poetry published in a newspaper. The fictional Edith is encouraged in her writing endeavours by the real Thomas Lister, the Barnsley Quaker poet, naturalist and advocator of Mechanics’ Institutes, and Ebenezer Elliot, known as the Corn Law Rhymer. But the background for more local colour must have come from elsewhere. Always interested in local history and topography, she would have seen Whitaker’s History of Craven which had reached its third edition by 1878. She was known to use maps as writing aids, so she most probably had, for example, the 1847 6 inches to 1 mile Ordnance Survey map of Giggleswick in front of her as she wrote, as the descriptions of the village layout are so vivid (Figure 3). Her brother was a Giggleswick pupil in 1833 and would no doubt have told her of schoolboy goings-on. Mrs. Esther Cragg (née Varley) was Isabella’s great-aunt and was visited at least once in Giggleswick by her around 1845 (according to an article written for the Manchester City News in 1885) . Well Bank of the book would be Bankwell, and the 1851 census has Elizabeth Cragg living at Ivy Court (sic) in Giggleswick. Isabella describes the novel’s Ivy Fold in such minute detail that she must have known it intimately - Ann Varley was living there in 1849 at the time of her death. Isabella is following the good advice given to authors - write about what you know about - even though it was fifty years later.

What did the book reviewers of 1880 have to say about this very locally rooted book? The Literary Examiner of 7 August 1880 considered that ‘Though there is but very little strong interest in the novel, there is no want of quietly amusing incident and pleasing description. As the main feature of the plot turns on the question as to whether a young man did or did not dress himself up as a ghost, it can be guessed that there is no great sensational excitement to be expected’. However (damning with faint praise) the book was felt to be readable, and was commended to patrons of circulating libraries. Clearly much of the interest of the book would be lost on those who were unfamiliar with the area or with the history of the 1830’s.

The Graphic (14 August 1880) considered that Mrs. Banks ‘without any large measure of dramatic power, or of skill in putting a story together has the art of reproducing the manners and customs and the peculiarities of thought and feeling that belonged to provincial England fifty years ago, and of bringing them to life again. ... The scene is laid in Craven, when Leeds was first enfranchised, when railways were new wonders, when, in remote districts, people still lived in the fashion of a hundred years before, while the great towns of the North were becoming conscious of new life and power’. The review went on to describe how the private lives of her characters were mixed up with the public affairs and movements of the time, information obviously gleaned by the writer from those taking part in them. The Graphic thought the story badly arranged, and having other defects from a literary standpoint, but the minor characters were admirable portraits obviously drawn from life. But all in all, the novel was considered excellent, and recommended not only to those interested in Yorkshire, but to all readers ‘who care for manlier food than that wherewith novelists commonly supply them’.

Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper reviewed the novel on 18 July 1880. To quote: ‘No novel could be more thoroughly wholesome and satisfactory in tone The bad man who flourishes like a bay tree during the first and second volumes, and the greater part of the third, is covered with ignominy before the close of the book, and the deserving men and women are properly rewarded; and all this comes about without any strain upon one’s incredulity. Mrs. Banks has displayed ... a singular power of description of bygone themes’ dealing with the Yorkshire of the 1830s and mentioning George Hudson the railway king and Edward Baines and his work in the education field. Lloyd’s considered the story had a clever plot, there was ‘no puling sentimentality in her love-passages, no lingering on the confines of delicate questions in her pages, no hinting at the breaches of the one Commandment on which so many modern novels turn’. I think the Graphic and Lloyd’s reviewers have both hit the nail on the head.

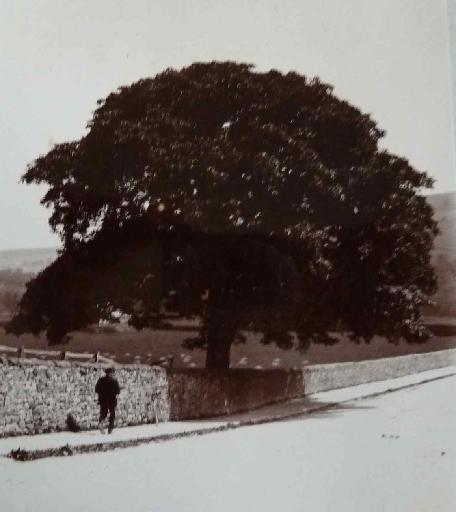

So ingeniously does the novel’s storyline incorporate actual places, personalities and happenings, both local and national, that one suspects many other incidental details described also to be true. We know there was a Parish Umbrella Tree between Settle bridge and Stackhouse Lane, mentioned twice in the text, because there is a photograph of it, labelled The Umbrella Tree, in Thomas Brayshaw’s scrapbook held in the Brayshaw Library, Giggleswick School (Figure 4). Dr. Burrow did live at the corner of the Market Place, but was it really nick-named Lazy Corner because idlers lounged there? Was Apple Tree Hall a reality? The real Osmanthorpe is near Southwell in Nottinghamshire - was Isabella thinking of another specific pit village near Barnsley? I am sure some readers will know the answers to these questions.

To finish, I can do no better than to quote again Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper: ‘There are many passages in the three substantial volumes that might be quoted with advantage and pleasure to the reader; we will, however leave those persons who are attracted by the account we have given of Wooers and Winners to secure the volumes and read the book through for themselves’. To access a copy, try through the library service, look on www.archive.org , Google the title or borrow mine!

Acknowledgement

The image of the Umbrella Tree is taken from Brayshaw’s scrapbook, vol.2, by kind permission of Barbara Gent of Giggleswick School.

References

- Banks, Mrs. G. Linnĉus, 1876. The Manchester man. Hurst and Blackett, London.

- Banks, Mrs. G. Linnĉus, 1880. Wooers and winners, or, under the scars. A Yorkshire story. Hurst and Blackett, London.

- Brayshaw, T. and Robinson, R.M., 1932. A history of the ancient parish of Giggleswick. Halton and Company Ltd., London.

- Buckland, A., 2013. Novel science. University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

- Burney, E.L. 1969. Mrs. G. Linnĉus Banks. E.J. Morten, Manchester.

- Dawkins, W.B., 1874. Cave hunting. Macmillan and Co., London.

Figure captions

Figure 1 Varley Family Tree

Figure 2 Gravestone in St Margaret’s Churchyard, Hornby

Figure 3 Giggleswick in 1847 from OS six-inch series. Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland. https://maps.nls.uk/index.html

Figure 4 The Parish Umbrella Tree. Photograph (n.d.) from Thomas Brayshaw’s scrapbook, volume 2, courtesy of Barbara Gent, Brayshaw Library, Giggleswick School.