| JOURNAL 2018 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

Introduction

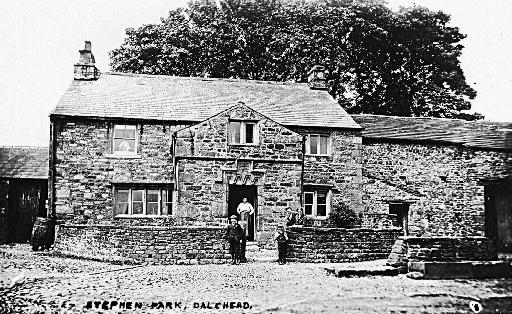

Stephen Park is a former farmed settlement situated 5 km north-east of Slaidburn, within the Forestry Commission’s plantations of Gisburn Forest. The Park was within the old district of Dalehead, acquired in stages by the Fylde Water Board in the 1910s and 1920s for water catchment to feed Stocks Reservoir. The former hamlet of Stocks-in-Bowland is below the water. Most of the Forest is conifer, but sloping down from the Park buildings to the principal watercourse of Bottoms Beck is Park Wood, an Ancient Semi-Natural Woodland. The farmhouse (Fig. 1) and associated buildings are currently the centre of a recreational hub of cycling and walking trails, and offices.The earliest date-stone in the buildings is 1662, but the settlement predates this. The earliest use of the place-name noted by Smith was in 1538 as Stevynparke [1] but in the Manor of Slaidburn Court Rolls is a 1533 entry for Stevenparke [2]. Prior to this date, the Park was associated with the Hamerton family, lords of the manor of Hamerton, modern Hammerton. ‘Hamereton’ was recorded in Domesday, the vill now designated a Deserted Medieval Village situated east of the River Hodder, and associated with the seventeenth century Hammerton Hall (Fig. 2) and lands to the east extending onto Hammerton Mere, approaching the Park in the modern forest (Fig. 3).

Stephen Park is generally described as a medieval deer-park held by the Hamerton family. From the place-name alone, it is understandable to assume that the Park was an authorised deer inclosure like its near neighbours Bashall, Leagram and Radholme parks. An archaeological survey by North West Water (NWW) of their Bowland estate describes the Park as ‘a fourteenth century deer park established by Stephen de Hammerton’ [3], a claim repeated in the Lancashire Historic Environment Record [4]. Dixon suggests that the Park farmhouse was ‘built in 1662 on the site of a hunting lodge’ [5]. An architectural survey of the site undertaken in 1999 (and other publications [6,7]) repeats this view [8]. None of these sources cite primary historical evidence to support the designations?but was Stephen Park unquestionably a deer-park?

To clarify the history of the Park, its purpose, and the role of the Hamerton family in its creation and management, documentary research and a field survey were undertaken:

a. the identification and review of original manuscripts and printed primary sources such as Chancery rolls, that could state or indicate that deer were imparked at Stephen Park;

b. an exploratory survey of the boundaries of the Park settlement, particularly the ditch and bank design, to provide insights into stock or deer movements, exclusion and enclosure?do the boundary remains show the characteristics of imparked deer retention, or wild deer exclusion?

The documentary study considered the period from the twelfth to the sixteenth centuries, terminating just after the execution of Sir Stephen Hamerton in 1537 for treason, and the disposal of his lands by the Crown.

A third aspect of the research?not discussed here?was a review of the long-published pedigrees of the Hamerton family. Primary sources were sought to substantiate and enhance aspects of the biographies of the principals, and provide new insights into grants, land improvements and other economic and social activities of the family, their rise and demise.

This paper provides an overview of the research strategy and outcomes; a more comprehensive report, that includes the work on the Hamertons, is available upon request to the authors.

The search of historical records

An introduction to the purpose and history of deer-parks will set the legal, social and economic context, and illustrate the documentary evidence sought to indicate an authorised deer-park in the medieval period.

Deer-parks

Hammerton was under the ambit of the Master Foresters of Bolland (Bowland) as a purlieu, even though not technically within the bounds known from fifteenth century and later surveys [9]. (A purlieu was disafforested land still subject to some aspects of forest law). The Forest of Bowland was created by William II and granted to Roger de Poitou in 1092, the first Lord of Bowland. It remained a private chase until the late fourteenth century when it came into royal ownership through the Duchy of Lancaster, but in 1661 it was granted to George Monck as Duke of Albemarle [10]. Thus, at different periods in its history, it was a royal forest or a chase. Many forests had deer-parks within or just outside the forest bounds. Private deer-parks were subject to scrutiny by forest officers to ensure that the parks did not harm the forest, particularly regarding entrapment of royal deer or escape of park deer and damage to the browse.Parks were owned by the Crown, nobility, bishops and the upper echelons of the gentry. Their purpose was to breed, succour, hunt and gift deer for the provision of the elite meat, venison. Deer-parks were expensive enterprises, providing a demarcated, private area of wood-pasture and open grazing. They were enclosed by a high fence of timber, stone or hedge, and associated ground-works such as a ditch and bank, collectively known as a ‘pale’. Deer-parks were prestigious and coveted areas and were subject to control by the Crown. In in the medieval period, a licence was required to make a deer-park although in practice, not all were licenced, such as when the Crown/Duchy owned the park (licences for Leagram and Radholme deer-parks are not known) [11]. The deer species enclosed in parks were principally fallow and red.

The licence, royal grants and continuing maintenance may leave documentary evidence. For a medieval deer-park:

- a licence for deer imparkment, the authorised enclosure of woodland containing deer coverts, or subsequently, rents from a grant of agistment upon disparkment (the leasing of former parkland for raising cattle and herbage);

- pleas to the Crown/Duchy for trespass by others and unauthorised taking of deer;

- accounts for maintenance of the pale, lodge, woodland, and supply of winter fodder;

- payments to the parker and staff;

- royal grants of live deer or venison and associated fees;

- inquisitions into the harm to the king’s forest arising from private imparkment;

- licences and accounts for salters (deer-leaps) to populate the park (salters were modifications to the park pale to enable wild or escaped deer to enter, but thwart their return [12]).

Licences for Bashall Park and an account of the ‘breaking’ of the park illustrate the type of records sought for Stephen Park. In 1465-6, a private deer-park was granted to Thomas Talbot ‘for ever’ [13]:

The licence of including a close, called Bashall Park, ... [and free warren] … provided that there is not a deer-leap, commonly called a Saltree [salter] [14].

The exclusion of a private salter?which would entrap royal deer?confirmed that this was a deer-park. In 1516, Edmund Talbot was licenced to impark lands in Bashall; he could:

enclose [a close] with palings, ditches and hedges … notwithstanding that some part of the said park may lie within the bounds of the king’s forests or chases … no one shall enter the said park to hunt there without licence from the said Edward [sic] on penalty of 40l. to the king [15].

Things did not go well?a Star Chamber pleading noted that 560 rods (3.6 km) of fence pales were thrown down by a mob of four hundred the following year; they also assaulted and threatened his park servants, their actions supposedly instigated by Edward Stanley, Lord Monteagle [16]. The gentry, nobility and church were not averse to breaking each other’s parks.

Enlargement of a park by Sir Stephen Hammerton

An important starting point is a return from the 1517 Inquisitions of Depopulation by the Chancery into the inappropriate enclosing and depopulation of land in England, largely driven by the economic advantage of sheep farming over arable [17]. Records from Yorkshire survive [18]:

Stephen Hammerton knight in the enlargement of his park &c. He enclosed in the same park 20 acres then plough land and that Stephen Hammerton is tenant in respect thereof [19].

Where was this park, and was it used to keep and hunt deer? Upon the marriage of Adam de Hamerton to Katherine de Knolle in the fourteenth century, the family acquired Wigglesworth, Hellifield and Knowlmere manors. They made Wigglesworth manor their principal home and ‘had a park about it’ according to Whitaker, and ‘the fact is certain, but I have never met with the Licentia Imparcandi [licence to impark] [20]. There was still a park there in 1538 when Richard Crumwell leased the site of Wigglesworth manor ‘and the herbage and pannage of Wiglesworth Park’ from the Crown, following the attainder of Sir Stephen Hamerton (below) [21].

The location of the enlarged park was not given in the inquisition returns, which was unusual. This infers that its location was already given in the name of the tenant?Hammerton [22]. The 1517 inquisition offered no specific date for the park enlargement, but the commissioners were instructed to consider inclosures from Michaelmas 1488 [23]. There were two knighted Stephens, the senior died in 1500 and his son John, fathered a Stephen around 1494, also knighted but executed in 1537 for his involvement in the ‘Pilgrimage of Grace’.

Which Sir Stephen enlarged the Park at Hammerton? Stephen senior was made knight-banneret in 1482 [24] but it is not known precisely when his grandson was dubbed. In 1528, plain ‘Stephen Hamerton’ (jnr.) was named amongst West Riding lords, knights and gentry as a commissioner of the peace [25] and also untitled in 1532 as a commissioner for the reformation of West Riding weirs and fish-garths [26]. His knighthood must have been conferred between 1532 and his death in 1537. Although Leadam favours Stephen junior as the park enlarger [27], he was not a knight within the Inquisitions of Depopulation accounting period and therefore the park enlargement by ‘Stephen Hammerton knight’ must refer to his grandfather. We know that although Sir Stephen senior was ‘of Wiglesworth’, he also retained a ‘mansion at Hamerton’ [28].

‘Stephen’ was a recurrent name in the Hamerton family, but which Stephen founded the Park? The 1501 Inquisitions Post Mortem (IPM) of Sir Stephen senior listed many holdings [29]; he was plainly a wealthy and influential man, but could he have afforded a deer-park, and did he attract royal patronage? There were also (at least) two Stephen Hamertons between the twelfth and fourteenth centuries: 1. The Kirkstall Coucher (c.1196) reveals a grant by ‘Stephanus de Hamertone [of] 20 cart-loads of hay with the appurtenances in the township of Hamerton … so that the monks will mow the hay and make with me a close near to a meadow in which now they take the said hay’ [30]. In a 1257-8 IPM after the death of Edmund de Lacy it was noted that Edmund held 30 acres of arable and eight of meadow in demesne within Slaidburn, but ‘Stephen of Hamerton holds all Hamerton by charter and pays 8 s. a year for everything’ [31]. 2. In the Knights’ Fees of 1302-3 in Hamerton, another Stephen de Hamerton held one carucate [32] and was also a benefactor of Kirkstall Abbey, giving 15 cart-loads of hay from Hamerton [33]. He founded a chantry in the chapel of St Mary, Hamerton in 1332 and for sustenance ‘gave 2 messuages, 36 acres in land, and 20 acres of meadow in Slayteburne and Newland in Bowland [held of the king (34)]’ [35]. This transfer to the church required a licence and a fine of six marks [36]. It is worth noting that imparkment in England grew from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries and reached its zenith around 1300 when there were about 3,200 parks, occupying up to 2% of the land area [37], and containing about one quarter of its woodland [38]. In this period, only about one in five senior gentry were deer-park owners [39]. It is perhaps a stretch to class the two foregoing Hamertons as ‘senior gentry’. Thus, there were (at least) three Stephens who could have founded the park prior to the enlargement noted in the 1517 account?but was it a deer-park?

The search for evidence of a deer-park

An exhaustive search of catalogued historical records in the national and local archives, and printed primary sources translated and edited by scholars in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, failed to find any indisputable or even indicative evidence of authorised (or illegal) deer inclosure in Stephen Park. The absence of evidence is not evidence of absence-it cannot be stated unequivocally that Stephen Park was not an authorised deer-park, but it is certainly most unlikely.It must not be assumed that the place-name ‘park’ is necessarily a deer-park. In Cumbria, ‘park’ was associated with enclosed woodland, not necessarily containing farmed deer [40] and in Scotland it could refer to fenced pasture for farm livestock [41]. In Yorkshire, ‘park’ was used from the twelfth century and applied to small enclosures and assarts (larger enclosures taken?often without permission?from the common or waste for farming stock, or for arable use) [42]. For example, in 1312, Drax Priory and Rievaux Abbey agreed on the ownership of tithes in Bingley, including ‘Ox-park’ and ‘Calve-park’, indicative that these ‘parks’ were cattle enclosures [43].

In the Crown’s accounts of the disposal of Sir Stephen’s lands is evidence that the Park was used for conventional farming activities. In 1538, Leonard Warcopp, an officer at arms, leased for 21 years ‘a chief messuage in Bolland’, part of the possessions of the recently executed Sir Stephen, late in the tenure of John Proctour (the property had reverted to the king upon the death of Elizabeth, Sir Stephen’s widow) [44]. The messuage was probably in Hammerton because Proctour had made a plea to the Duchy in 1537-8 that Sir Stephen had harmfully forced entry and taken possession in ‘Hammerton Manor’ [45]. In 1546, Ralph Greneacre of Sawley was granted the lordship and manor by the Crown when they had reverted from Warcoppe [46]. In a list of tenants was:

our house and garden called Steven Parke and 4a of arable land, 5a of meadow and 40a of our pasture and moss with the appurtenances and now or late in the tenure of the relict of George Parker or her assigns [47].

Plainly this was a farmed area in the 1540s and there is no doubt that an authorised and functioning deer-park would have been highlighted. The Parker sons continued farming there until the male line died out in the 1570s [48].

Just after the Crown’s grant to Greneacre in 1546, he was granted a licence to transfer lands in Bowland to Oliver Breres, whose descendants undoubtedly built the new Hammerton Hall [49]. A 1621 inventory of a later Oliver Breres mentions an ‘olde hall’ and a 1679 indenture discusses both a ‘New Hall at Hamerton’ and an ‘Old Hall’, implying that house may have been built in stages [50].

Field survey

Survey area and the boundaries

The purpose of the field survey was to identify landscape features that may indicate the former presence of a deer-park: curvilinear boundaries contrasting with angular linear boundaries of later enclosures; remains of the pale system, the ditch being within the park; place-names reflecting a former deer-park such as Pale Wood or Laund etc.

Curvilinear boundaries were also a feature of assarts in which the settlement boundary would be designed to keep deer out and away from crops and herbage (a ‘deer-dyke’). The relative positions of the ditch and bank of the boundary are important?a ditch on the outside of an assart or park boundary would indicate a desire to exclude deer, rather than retain them. The survey focussed principally on the ditch and bank arrangements of the outer bounds of the Stephen Park assart, but this required a judgement on the location of the original enclosed area.

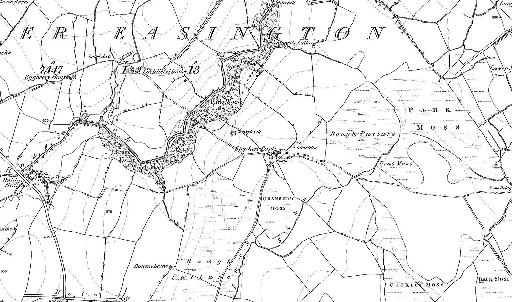

A comparison of the first edition OS 6-inches to 1-mile map (surveyed 1847) and the modern 1:25,000 of the Park area is shown in Fig. 4; the earliest large-scale map is the 1844 tithe commutation plan, Fig. 5 [51]. A curvilinear boundary is evident (less conspicuous in the south-west) encompassing Park Wood and bounded in the west by Bottoms Beck. The working assumption was that this boundary was a putative deer-park enclosure, and/or the original assart boundary. Some of the inner compartments could have been used to keep deer, and so the internal boundaries were also surveyed. The survey area was 69 hectares (170 acres), with a circumference of 3.5 km.

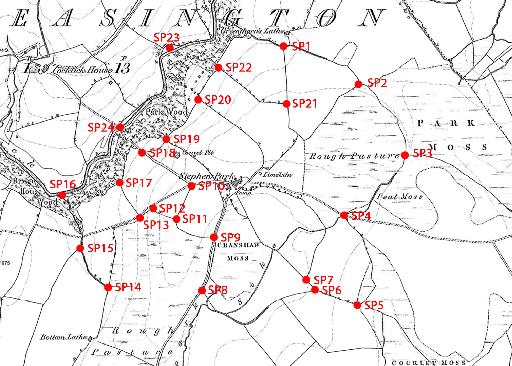

The practical approach in the dense forestry plantations and moss was to focus the inspections at or near numbered ‘nodes’, junctions between the compartments and the outer bounds, and between internal compartments (Fig. 6). One metre resolution Digital Terrain Model LIDAR was also employed but is not discussed here.

It was evident that many of the pre-forestry boundaries had been employed as plantation borders, or as access/firebreaks. In the mossy areas such as Park Moss, historical banks and ditches were frequently not evident due to dreadful ground conditions and self-seeded conifers. Most banks had associated ditches (Fig. 7), some of which were water-filled (Fig. 8), but there were isolated boundaries with no evidence of ditching (Fig. 9). Figure 10 shows a curvilinear bank and internal ditch above a small stream, which served as the boundary between Park Wood and Bridge House Wood. This bank separated a small section of Park Wood from former pasture, now woodland.

East of the Park farmhouse along the old track east towards Tosside, was a substantial ditch and bank (c. 1.5 m high), originally between arable and meadow enclosures (Fig. 11). This was the highest historical bank feature in the park, but being parallel to a track may have been modified recently. The eroded boundary between the long-established Park Wood and the former meadows and pastures of the Park (now under trees) is shown in Fig. 12.

Survey synopsis

The boundaries shown on the nineteenth century mapping were largely still evident on the ground, even within forestry plantations, but nearly all signs of the boundary bank/ditch in east and north east outer bounds were lost in the moss and disturbed ground. The survey provided no evidence of circumferential deer-park pale groundworks designed to retain deer within the Park, nor evidence of internal deer paddocks. The ditches, where present on the bounds, suggested that the bank and ditch system was designed to exclude animals from the park interior, undoubtedly wild deer and the stock of other landowners/tenants grazing on unenclosed land.

There was little stone walling but some banks had evidence of hidden foundations?occasional loose stones and sub-surface obstructions. Some of the banks were substantial suggesting that walling was not universal as a boundary fence in the park, and that live hedging was probably the norm. It was not possible to determine the age of the banks from such a superficial survey, and no evidence was forthcoming in the documentary research to reliably date the assarting.

Discussion

It is concluded that Stephen Park was not a pre-sixteenth century deer-park. The name element ‘park’ is not presumptive evidence that enclosures contained lawfully introduced deer or imparked wild deer. But hunting would undoubtedly have taken place in the area, indeed, in c. 1242 William de Percy granted the manor of Gisburn and the forest to Sawley abbey but retained the right to hunt [52], and in the early fourteenth century, Henry de Percy had a chase in Gisburn forest in which he reserved the hunting, and the abbot of Sawley had the wood and herbage [53]. The debate is not whether deer hunting occurred, but whether deer were imparked.

The earliest recorded use of the place-name was the early sixteenth century when the land was held by Sir Stephen Hamerton (jnr.) There was no evidence that his grandfather or indeed any of the Stephens before him, named the park. The elder Sir Stephen had extended the park. The 1488-1517 inquisition was the earliest use of the place-name element ‘park’ for the area. Around the time of the examination, trial and execution of Sir Stephen, there was evidence from the Slaidburn manor court and Crown audits of his confiscated lands, that Stephen Park was used for conventional mixed farming activities by tenants.

If Stephen Park as a place-name originated in the late fifteenth or early sixteenth centuries, it is not known if the area was separately identified within Hammerton in the medieval period. It is known that there were pastures and enclosures in the Hesbert Hall area (immediately north of Stephen Park) in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries [54,55]; for example, in 1269 there was an agreement between Sawley abbey and the prioress and nuns of Stainfield priory (Lincolnshire), that mentioned ‘clausis [enclosures] de Esbrichahe [Hesbert Hall] et Stodfalgile [Studford Gill] [56]. However, it would be unwise to include the later Park area in the grants because of the parish boundary between them, and uncertainty in the tenurial arrangements in the locale at that date. The grants showed that the general area had pastures for cattle and mares. It is not known exactly when the Park area was assarted, but from this indirect evidence, it is possible that it was used for cattle and horse pasture in the twelfth century and it may have been enclosed like Hesbert around the same time, but by whom is not known.

Frankly, we still know little of the history of the Park area before the sixteenth century. Its association with a notable knightly family in Yorkshire?that felt the wrath of Henry VIII for a (perhaps reluctant) involvement in the northern insurrection against his policies and attitude to the Catholic church?provides an historical background that should interest the many visitors to this popular area. That it appears not to be a medieval deer-park is disappointing. This contrary stance to the official view could fall on the emergence of a single undiscovered or overlooked historical record, and so the authors would be pleased to receive any primary evidence that the Hamertons imparked deer. We have certainly found accusations from queen Isabella in the 1330s that Hamertons were not averse to breaking her deer-park at Radholme in Bowland and carrying away deer! [57].

Acknowledgements

Chris Spencer translated sources and generously shared his knowledge of the area’s history.

Diana Kaneps discussed the Hamerton family.

Martin Colledge, Forestry Commission Bowland Beat Manager, provided a contribution to the expenses of the field survey and documentary research.

References

- A.H. Smith, The Place-Names of the West Riding of Yorkshire. Part VI: East & West Staincliffe and Ewcross Wapentakes (Cambridge/English Place-Name Society, 1961), p. 203.

- Pers. comm. Chris Spencer from the Manor of Slaidburn Court Rolls. According to Spencer, the Stout family were at Brigg/Bridge House during the 1500s to 1600s, Richard Hamerton was probably at Hammerton Hall and George Parker, and later his widow, farmed at Stephen Park from the 1530s onwards.

- North West Water's Forest of Bowland Estate, Lancaster: Archaeological Survey Report. Lancaster University Archaeological Unit, March 1997, p. 151.

- Lancashire County Council Historic Environment Record PRN13332 - MLA13329.

- J. Dixon, P. Dixon, Journeys Through Brigantia: Vol. 8, Circular Walks in the Forest of Bowland. (Barnoldswick/Aussteiger Publications, 1992), p. 121.

- Hodder Service Reservoir and Access Works, Slaidburn, Lancashire, October 2008, Oxford Archaeology North Report No. 2008-09/757 for United Utilities, p. 8.

- Notes by Diana Kaneps in A. Read, 'In praise of The Folly: Past, Present and Future'. North Craven Heritage Trust Journal, 2001, pp. 8-11.

- Stephen Park Slaidburn Lancashire: Archaeological Building Survey, January 2000, Lancaster University Archaeology Unit Report No. 1999-00/(040)/AUA 8944, p. 16. Available at Lancashire Archives DDX 1915/73/1.

- R.C. Shaw, The Royal Forest of Lancaster (Guardian/Preston, 1956), pp. 212-4.

- C.J. Spencer, S.W. Jolly, 'Bowland: The Rise and Decline, Abandonment and Revival of a Medieval Lordship', The Escutcheon, Vol. 15, 2010, pp. 3-5.

- S.A. Mileson, Parks in Medieval England (Oxford University Press, 2014), p. 139.

- G.J. Cooper, W.D. Shannon, 'The Control of Salters (Deer-leaps) in Private Deer-parks Associated with Forests: A Case Study Using a 1608 map of Leagram Park in the Forest of Bowland, Lancashire', Landscape History, Vol. 38 , Iss. 1, 2017, pp. 43-66.

- A Catalogue of the Harleian Manuscripts in the British Museum, Vol, I (London/The British Museum,1808), p. 444.

- T. D. Whitaker, An History of the Original Parish of Whalley and Honor of Clitheroe, Volume II (London/Routledge, 1876), p. 498. In Latin within Whitaker.

- Calendar of the Charter Rolls, Vol. VI, 5 Henry VI - 8 Henry VII, A.D. 1427 - 1516 (London/HMSO, 1927), p. 283.

- TNA Star Chamber Pleadings, STAC 2/26/345.

- E.F. Gay and I.S. Leadam, "The Inquisitions of Depopulation in 1517 and the 'Domesday of Inclosures'". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. 14, 1900, pp. 231-303.

- I.S. Leadam, 'The Inquisition of 1517 Inclosures and Evictions. Edited from the Lansdowne MS. I. 153. Part II'. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. VII, 1893, pp. 219-253.

- I.S. Leadam, 'The Inquisition of 1517 Inclosures and Evictions. Edited from the Lansdowne MS. I. 153. Part II'. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. VII, 1893, p. 244.

- T.D. Whitaker, The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven (London/Nichols, 1812), pp. 126-130.

- In 'Henry VIII: February 1538, 21-28', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 13 Part 1, January-July 1538, ed. James Gairdner (London, 1892), pp. 124-142. British History Online link [accessed 16 December 2017].

- I.S. Leadam, 'The Inquisition of 1517 Inclosures and Evictions. Edited from the Lansdowne MS. I. 153. Part II'. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. VII, 1893, p. 244.

- I.S. Leadam, 'The Inquisition of 1517. Inclosures and Evictions'. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. VI, 1892, p. 175.

- W.A. Shaw, The Knights of England Vol. II (London/Sherratt and Hughes, 1906), p. 17.

- 'Henry VIII: December 1528, 26-31', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 4, 1524-1530, ed. J S Brewer (London, 1875), pp. 2208-2254. British History Online link [accessed 22 October 2017].

- 'Henry VIII: January 1532, 11-20', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 5, 1531-1532, ed. James Gairdner (London, 1880), pp. 339-349. British History Online link [accessed 22 October 2017].

- I.S. Leadam, 'The Inquisition of 1517 Inclosures and Evictions. Edited from the Lansdowne MS. I. 153. Part II'. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, New Series, Vol. VII, 1893, p. 244.

- E. B. R. Tempest, Tempest Pedigrees MS, at 'Digitized version of the transcript of Eleanor Blanche Tempest's Tempest Pedigrees', Vol. 1, p. 107; Some Notes On Medieval English Genealogy, link [accessed 14 January 2015].

- Calendar of Inquisitions Post Mortem, Henry VII, Vol II, (London/HMSO, 1915), pp. 243-4.

- The Coucher Book of The Cistercian Abbey of Kirkstall in the West Riding of the County of York, Thoresby Society Vol. VIII (Leeds, 1904), pp.200-1.

- W. Brown, Yorkshire Inquisitions of the Reigns of Henry III and Edward I, Vol. 1 (Yorkshire Archaeological and Topographical Association, Record Series Vol. XII, 1891), pp. 47-8.

- R.H. Skaife, The Survey of the County of York Taken by John de Kirkby Commonly called Kirkby's Inquest. Also Inquisitions of Knights' Fees. Publications of the Surtees Society, Vol. XLIX. (Durham/Andrews, 1867), p. 197.

- T. Merrall, A History of Hellifield (Settle/Lambert, 1949), p. 96.

- National Archives C 143/214/1.

- Yorkshire Indexers, from the Torre Manuscripts, Slaidburn 136, Hamerton, available at link, accessed 18 May 2017.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 2, 1330-1334, 11 October 1331, p. 213.

- O. Rackham, The History of the Countryside (London/Phoenix, 1986), p. 123. An average park area of 200 acres was used for the estimate.

- O. Rackham, Trees and Woodland in the British Landscape (London/Phoenix Giant, 1996), pp. 152-153.

- S.A. Mileson, Parks in Medieval England (Oxford/Oxford University Press, 2009), p. 109.

- A.J.L. Winchester, 'Baronial and Manorial Parks in Medieval Cumbria' in R. Liddiard, The Medieval Park: New Perspectives (Macclesfield/Windgather, 2007), p. 166.

- J. Fletcher, Gardens of Earthly Delight: The History of Deer Parks (Oxford/Oxbow, 2011), p. 587.

- S. Moorhouse, 'The Medieval Parks of Yorkshire: Function, Contents and Chronology' in R. Liddiard (ed.), The Medieval Park: New Perspectives (Macclesfield/Windgather, 2007), pp.101-2.

- J.H. Turner, Ancient Bingley: Or Bingley its History and Scenery (Bingley/Harrison, 1897), p. 118.

- 'Henry VIII: May 1538, 26-31', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 13 Part 1, January-July 1538, ed. James Gairdner (London, 1892), pp. 393-416. British History Online link [accessed 16 December 2017].

- Ducatus Lancastriae, Calendar to the Pleadings Etc, Vol. III (House of Commons, 1834), p. 157.

- 'Henry VIII: April 1546, 26-30', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 21 Part 1, January-August 1546, ed. James Gairdner and R H Brodie (London, 1908), pp. 334-359. British History Online link, p. 354 [accessed 20 October 2016].

- TNA C 66/781 m. 16.

- Pers. comm. Chris Spencer.

- 'Henry VIII: November 1546, 21-30', in Letters and Papers, Foreign and Domestic, Henry VIII, Volume 21 Part 2, September 1546-January 1547, ed. James Gairdner and R H Brodie (London, 1910), pp. 203-248. British History Online link [accessed 13 October 2016].

- Pers. comm. Chris Spencer.

- Tithe Map of the Township of Easington in the West Riding of the County of York. Dated 1844. Fylde Water Board copy held in Slaidburn Archive.

- J. McNulty, The Chartulary of the Cistercian Abbey of St Mary of Salley in Craven, Vol. I (Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series LXXXVII, 1933), p. 20.

- Calendar of the Inquisitions Post Mortem and Other Analogous Documents, Vol. V, Edward II (London/HMSO, 1908), pp 312-3.

- W. Farrer, C. T. Clay, Early Yorkshire Charters: Vol. 11, The Percy Fee (Cambridge Library Collection - Medieval History, 2013), pp. 56-7.

- C.T. Clay, W. Farrer, Early Yorkshire Charters: Vol. IX, The Percy Fee (Yorkshire Archaeological Society Record Series, Extra Series Vol, IX, 1963), pp. 79-80.

- J. McNulty, The Chartulary of the Cistercian Abbey of St Mary of Salley in Craven, Vol. I (Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Record Series LXXXVII, 1933) p. 25.

- Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 3, 1334-1338, 24 June 1337, pp. 452-453, Calendar of Patent Rolls, Edward III, Vol. 3, 1334-1338, 12 July 1335, p. 201, et al.

Figure 1: Stephen Park farmhouse in the early twentieth century (Slaidburn Archive).

Figure 2: Hammerton Hall, built in the 17th century, probably by the Breres family, on the site of an earlier hall.

Figure 3: Hammerton Hall, Hammerton Mere, and in the distance Gisburn Forest plantations with Stephen Park within. Note that the modern Gisburn Forest FC estate extends west of the historical Gisburn legal forest, and the modern civil parish.

Figure 4: A comparison of the Stephen Park area in the 1840s and today. Upper: the first edition OS 6-inches to 1-mile, surveyed 1847, published 1850. Lower: modern 1:25,000 OS. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right (2018).

Figure 5: Extract of a tithe map of Upper Easington redrawn by the Fylde Water Board, and held by Slaidburn Archive. The curvilinear boundary to the north, east and south-east of the settlement is suggestive of an early assart. The map has been digitally enhanced.

Figure 6: Boundary nodes and other features subjected to an exploratory survey, shown on the 6-inches to 1-mile (1:10,560) OS map surveyed in 1847.

Figure 7: A bank and ditch near node SP10 heading downhill towards Park Wood (not visible), which on the 1847 6-inch and the tithe map bounded a meadow, now with trees.

Figure 8: West of SP6, a bank and a ditch with flowing water. The pole is 1 metre.

Figure 9: SP1 - An historical bank without a ditch.

Figure 10: SP16 - a bank and ditch on the south-western boundary of Park Wood. To the left of the ditch is the former Calf Meadow, now wooded.

Figure 11: A bank and ditch heading from the farmstead to SP4.

Figure 12: The former boundary of Park Wood (top right) with meadows, between SP18 and SP17. The pole is on top of the eroded bank.