| JOURNAL 2019 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

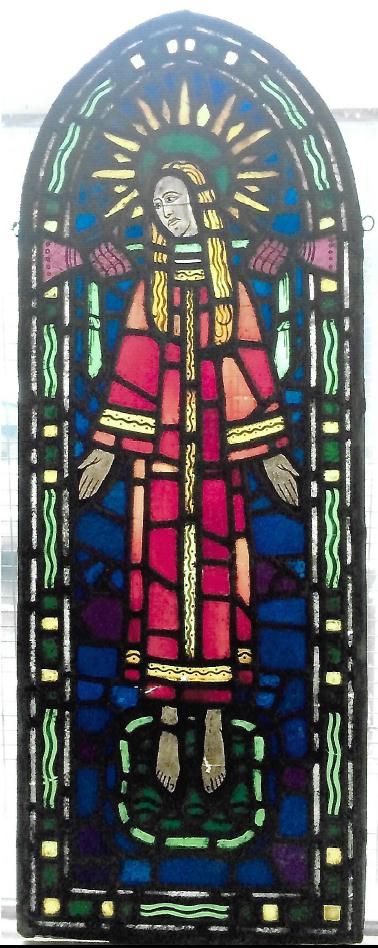

During 2014, two church members from St Alkelda’s Parish Church in Giggleswick were looking for items to sell at a church fair in the Parish Room which is situated just off Bankwell Road. This seventeenth-century private dwelling had been bought by the church in 1932 and was for some years until the early 1960s linked to the then vicarage by means of a door into the main meeting room. The two people were searching an adjacent room, once used as a kitchen scullery, which had been more recently a storage space for chairs and a dumping ground for odds and ends. Under a dusty pile of newspaper and wood on a stone slab shelf, they spotted an item of stained glass. It had been seen some years before, but ignored. In 2014, for various reasons, it was left for some time before it was brought to the notice of other members of the congregation. As the whole piece emerged they appreciated that even in its dusty state, it was an item of considerable beauty. They thought at first they were looking at a stained glass representation of an angel. The priest in charge, the Revd Hilary Young, to whom it was shown, pointed out that the lady in the stained glass panel was being strangled with a green cord pulled by two gauntleted fists and that her feet were in water, probably in the water of her holy well. The lady in the stained glass panel must be the artist’s representation of St Alkelda.

Several of us have been in touch with former vicars’ family members, who have memories which go back to 1955. No one can recall the stained glass panel being brought to the vicarage, nor does anyone recall ever having seen it. It could not have been there before 1932 when the house was in private hands. So many questions are still unanswered. Who was the stained glass artist? Why was it put in a storage room in the first place? Had it been brought to be considered for display in the church and then rejected? Was the piece considered too ‘catholic’ for a church of the low-church Anglican tradition? Had the powerful influence of Thomas Brayshaw something to do with its rejection? 1932 was the date of his posthumous publication, the celebrated A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick.

Though St Alkelda may have been an historical person who lived in Middleham considerable doubt is cast on the name attributed to her. ‘Alkelda’, as several authorities have pointed out, is an Old English-Norse composite name very likely from the word haeligkeld meaning holy well. My guess is that it was an affectionate nickname for a saintly lady famous in the localities of Middleham and Giggleswick for her use of holy wells as Christian baptism sites for converts. In Giggleswick and possibly in Middleham, the churches probably took their designation from the name of the saint associated with their holy wells as York Minster did from St Peter’s well over which it is built. In the medieval period, people travelled on the ancient trackway between Middleham and Giggleswick via Coverdale, Kettlewell, Kilnsey, Malham and Stockdale. This route is ‘as the crow flies’, and is about half the distance of the route taken by the modern road via Hawes and Ribblehead. (See the NCHT Journal 2015, St Alkelda Re-visited, Holy wells and South-side Crosses — by K. Kinder, for recent research from both Middleham and Giggleswick.)

Thomas Brayshaw in A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick writes somewhat disparagingly of St Alkelda’s credentials in two paragraphs, pages 228-9. Of course, there is, to quote Brayshaw, ‘no concrete evidence’ of St Alkelda coming to Giggleswick, but in the experience of many modern researchers where there is a long-term ancient tradition to consider, it is best to have an attitude of respectful agnosticism, leaving all possibilities open. Sometimes, the findings of modern archaeology give credence to ancient traditions. Indeed, during the renovations at the church of St Mary and St Alkelda in Middleham in 1878, there was dug up in the nave, at the point where the centuries-old tradition had said St Alkelda was buried, an ancient stone coffin containing the bones of a woman. Thomas Brayshaw took Dr Whitaker to task for his inadequate treatment of the ancient parish of Giggleswick. Brayshaw writes on p.143 of A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick,

‘Readers of Whitaker’s History cannot fail to note that the learned author’s chapters on the parishes of upper Ribblesdale do not show the first-hand information that is abundantly evident when he writes of Skipton or Bolton Abbey, or Gisburne or Bolton by Bowland’.

Thomas Brayshaw writing in the Craven Herald, July 1920, also criticises Dr J Cox’s The Parish Church of Giggleswick in Craven on similar grounds. Yet in chapter two where Dr Cox lists Giggleswick’s financial dealings with Finchale Priory (which had control of the parish for most of the Middle Ages), Brayshaw missed the intriguing entry for1376-7. ‘Expenses connected with the churches of Giggleswick and Middleham amounted to £5.4s.10d’ .Present-day members of the Giggleswick congregation are asking many questions relating to this entry, which surely strengthens the claim that these two churches, some 33 miles apart, as the crow flies, had a common link. If that link is not St Alkelda, who or what else?

Middleham Church does not appear to have had the close connection with Finchale Priory which Giggleswick had during the Middle Ages. It was Richard III, then Duke of Gloucester, and not the monks of Finchale Priory, who organised Middleham into the collegiate church of St Mary and St Alkild in 1480, just over a hundred years after the joint entry with Giggleswick in the Finchale Priory records. The Revd Jeff Payne, present rector of the Jervaulx group of churches, kindly looked up the medieval archives. Middleham Church has never been under the control of Finchale Priory, yet in one of his Papers, Thomas Brayshaw said it had. The historical fact makes the1376-7 entry in Finchale Priory records relating to Giggleswick and Middleham churches even more intriguing.

When it came to researching all the material relating to St Alkelda, Thomas Brayshaw was guilty of the same fault of which he accused Dr Whitaker and Dr Cox. In A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick, Thomas Brayshaw, an acknowledged authority on St Alkelda’s connection with Giggleswick, gives no indication that he had ever researched the traditions and medieval documents relating to St Alkelda and based on Middleham which Dr Heather Edwards has researched and published [Edwards, 2004].

When it comes to reaction to the discovery of the St Alkelda stained glass panel, most of today’s congregation of St Alkelda’s Church have certainly not been influenced by Thomas Brayshaw’s attitude at all. The discovery has roused a great deal of positive interest in the last two years amongst members and friends of the church, so much so that money has been raised for the stained glass panel’s cleaning and restoration. We owe a debt of gratitude to our church wardens for all the work and enthusiasm they have put into the project. Since there was a unanimous desire that the panel should eventually be on view in the church, a faculty had to be sought. That has now been granted and the panel, cleaned,and restored was installed in St Alkelda’s Church in February this year. Two key questions remain: does the panel contain any medieval glass and what is the provenance of this art object, which even in its unclean state, is rather beautiful?

When Daniel Burke, director of Lightworks Stained Glass Ltd, specialist glaziers in Clitheroe, and his team, began to handle the panel, they noticed how heavy it was for its size. The weight was caused by some of the blue and red pieces of glass, mostly blue, which seem to have been produced by an ancient style of glass-making. These blue and red pieces of stained glass are thicker than the rest and are pitted on the back. We know from A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick p.226 that stained glass containing a preponderance of blue pieces was recorded in the East window of the church in 1620. A photograph taken during the alterations and renovations of 1890-92 shows East windows of plain glass. During the Commonwealth period, the Cromwellian troops under Major General John Lambert wreaked havoc in the churches of Craven. They had a habit of beheading crosses, smashing windows, wrenching carved heads off the walls and roof and then throwing the items into the graveyard. During 1890-2, a Green Man (the only one in North Craven?) was found half buried in Giggleswick church yard and re-installed in the church, above the pulpit canopy. Whether that was its original place, we do not know.

In the Preface to A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick, Ralph Robinson records Thomas Brayshaw’s activity during the restoration work done on the church in 1890-92:

‘While the work was in progress, he visited it almost daily, sifting the soil beneath the floor in search of some fragment broken from a monument in iconoclastic days, and always making notes of any discovery that might throw a glimmer of light upon the history of the fabric.’

Did Thomas Brayshaw find any broken bits of medieval glass, and did any by chance, find their way into the hands of the stained glass artist who created the St Alkelda panel? Again, we do not know. Lightworks Stained Glass advised the church to seek a higher opinion on the panel’s provenance. In 2017, the panel was taken to York Minster for the expert opinion of the York glaziers. In their judgment, the panel was modern, early twentieth century, probably 1920s -30s. The figure certainly seems to show some art nouveau influence, much in vogue during the early twentieth century. When it came to the pieces of blue and red glass, the York glaziers were “of the opinion” that they had been fashioned to make them look as if they had been created in the Middle Ages. The interesting point here is that the York glaziers could not give a definitive answer as to whether or not there was any medieval glass in the piece. They considered the panel to be ‘a significant piece of work’ and should be restored as far as possible with love and care to its original condition, and certainly that has been done to the highest possible standards. The congregation of St Alkelda’s are most appreciative. However, for the staff of Lightworks Stained Glass who have worked with the panel at close quarters, the questions will not go away. (Work now completed:Ed.).

The window may have been installed but the mystery and questions surrounding this artefact still remain for us all. Perhaps they will prove an added attraction to the many visitors to our historic and beautiful church? We plan a festival of celebrations June 15-6, 2019 and we hope as many people as possible will come and view this striking stained glass panel depicting the martyrdom of St Alkelda. A special invitation too will be given to the priest and congregation of the church of St Mary and St Alkelda at Middleham. Without them, the story, traditions and legend of St Alkelda would not be complete. With them, and under the guidance of the British Pilgrimage Trust and the support of the Anglican diocese of Leeds, we have begun to plan a modern pilgrimage walk along the ‘St Alkelda Way’, the 33 miles between our two churches. The route, mostly on prehistoric and Roman trackway, and featuring on a website, goes from Settle, Stockdale, Pennine Bridleway, Malham, Street Gate, Mastiles Lane, Kilnsey, Kettlewell, Coverdale to Middleham. At a time when the British Pilgrimage Trust is aiding the revival of old pilgrimage routes and helping the creation of new ones to satisfy a growing public interest, the ‘St Alkelda Way’ will be the only pilgrimage way lying almost entirely within the boundaries of the Yorkshire Dales National Park. Both churches involved are in the Ripon area of the Anglican diocese of Leeds, and one starting point/destination is in an area of keen interest to the North Craven Heritage Trust.

Acknowledgements

Barbara Gent — Archivist, Giggleswick School

Bibliography and References

- Brayshaw, T,, 1920. A Criticism of Dr Cox’s History of Giggleswick Church, Craven Herald, July

- Brayshaw, T., and Robinson R., 1932. A History of the Ancient Parish of Giggleswick, London

- Callan, R., Fox, D., Kinder, K., 2004. Bits, Scraps and All sorts from Giggleswick and Beyond, edited Nigel Mussett,, Kirkdale publications.

- Cox, J.C., 1920. The Parish Church of Giggleswick in Craven, Leeds, Richard Jackson

- Edwards, H., 2004. Yorkshire Archaeological Journal, vol. 76, pp. 135-144

- Kinder, K., 2015. North Craven Heritage Trust Journal, p.3 ff

- Mussett, N. and Kinder, K., 2016. The Stained Glass Windows of St Alkelda’s Church Giggleswick, Kirkdale Publications.

- Whitaker, T. D, 1805. The History and Antiquities of the Deanery of Craven, London

Texts available online

- https://englishhistoryauthors.blogspot.com/2017/03/st-alkelda-saxon-lady-martyred-saint.html

- https://www.jervaulxchurches.co.uk/

- http://www.megalithic.co.uk/article.php?sid=26303

- http://www.northcravenheritage.org.uk/NCHT/CummulativeIndex.htm p.3 (2015)

- http://www.richardiii-nsw.org.au/2010/11/st-mary-and-st-alkelda-middleham-north-yorkshire/

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Church_of_St_Mary_and_St_Alkelda,_Middleham

- British Pilgrimage Trust http://britishpilgrimage.org/

Lightworks Stained Glass Ltd — the St Alkelda Panel

Kathleen Kinder — St Alkelda Church Hanging (Barbara Thornton designer)