| JOURNAL 2021 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

More years ago than I care to remember, as a child I borrowed a copy of a book called Underground Adventure [1] from my local public library. I hadn’t realised it at the time but in my hands lay one of the true classics of British caving literature. It was co-written by Jack Myers and Arthur Gemmell during the 1940s (but not published until 1952, as there was a severe paper shortage immediately after the war). I devoured it from cover to cover and this book was probably one of the main reasons for me taking up caving, shortly afterwards. It’s a decision which I’ve never regretted.

The years rolled by and, in 1990, I had an invitation to write the introduction for a reprint of the book by Mendip Publishing [2]. I’d never come across Jack in person and remember feeling privileged that such an opportunity to meet the great man had fallen into my lap. Frank Butterfield (or ‘Buzzer’ as he was almost universally known) lived around the corner from Jack in Austwick, so he took me around to ‘Suncroft’ where Jack lived. As we chatted the hours away I became fascinated by the story of his extraordinary life. We became friends and I often exchanged letters or visited him after this first meeting.

Jack Osborne Myers was born on 25th March 1925 to parents Clara and Luther and as he grew up he proved both to be athletic and highly intelligent; these are useful attributes for a man who would go on to become, for a time, one of Britain’s hardest cavers. In 1945 he had graduated in geology (with mathematics) but was actively caving well before then. Early in 1944 he had been a member of the party which made the main exploration of Disappointment Pot (part of the Gaping Gill cave system underneath Ingleborough). Other notable involvement in discoveries included Notts Pott (Leck Fell) in 1946, Ease Gill Caverns and Lancaster Hole (Casterton Fell) over several years from 1946 and Penyghent Pot, from 1949 onwards. The latter is a very fine pothole on the east side of Ribblesdale, in which Jack had the dubious pleasure of having a feature named after him. He had attempted to glue together a two piece wartime-surplus lifeboat suit, with only partial success. The resulting “waterproof” caving suit became increasingly cumbersome as it started to fill up with the icy liquid. It caused him to slip off a vertical drop into a pool (which broke his fall, at least to some extent). No serious harm was done and, in a demonstration of typical cavers’ sense of humour, this shaft has been known ever since as ‘Myers’ Leap’.

Other exploratory work included the ingenious use use of a metal detector to re-locate what became known as Magnetometer Pot (Fountains Fell) following up stories of a former unexplored entrance having been covered over using steel rails and lost. Jack was also active in the Malham area, notably at Pikedaw Caverns, about which he produced some invaluable research material in later life. In this (and on many other projects) he made extensive use of aerial photographs; it was long before the use of such modern luxuries as ‘Google Earth’ satellite imagery became regarded as routine.

Throughout much of his period of active caving Jack worked as a lecturer and research assistant at Leeds University, in the Department of Mining. It was there that he gained his PhD in geophysics in 1958. (The reams of mathematical calculations in his thesis, completely unintelligible to us normal mortals, bears witness to Jack’s finely honed skills with numbers.) An overlap of professional expertise and a passion for all things underground also led to his being recognised as an authority on the mines and mineralogy of the Northern Dales area.

Some of Jack’s early caving was done as a member of the British Speleological Association, where he was often in the company of friend Gerald Bottomley, until the latter emigrated to the southern hemisphere in 1946. However, during that post war year, the BSA was experiencing severe differences of opinion between leading light Eli Simpson and a number of other prominent members. ‘Cymmie’ as he was known, had maintained the BSA’s headquarters at ‘Cragdale’ since before the war, in the grand building which would later become Settle police station until budget cuts led to it being turned into a block of flats recently. (I often wonder if the present residents have any idea of the rich history of that building.) Cymmie was evidently a dominant and dominating character; I suspect those returning from the great conflict had taken just about enough of being told what they should or shouldn’t do and, postwar, it led to a wholesale exodus of members, many of whom formed their own clubs. These included the Red Rose Cave and Pothole Club (now based at Bull Pot Farm on Casterton Fell) and the Northern Pennine Club (based at Crow Nest near Austwick for a while, then at Greenclose, Clapham).

Jack joined the ‘Pennine’ (as the NPC is generally known) around 1948, so he wasn’t quite a founder member. He soon became one of its most prominent characters. As one of his contemporaries put it, Jack was a ‘serious and scientific’ caver and seldom joined in with the more social aspects of caving club membership. Perhaps this was no bad thing as, without involving himself in the drinking and merriment typical of Saturday nights in those day, he would be up bright and early next morning, to encourage his bleary-eyed friends to join him on the descent of some fearsome pothole. Without his drive, many a Sunday caving trip would not have taken place.

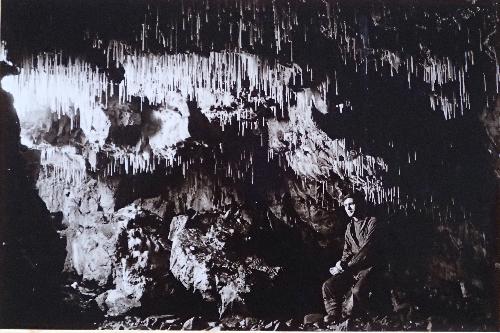

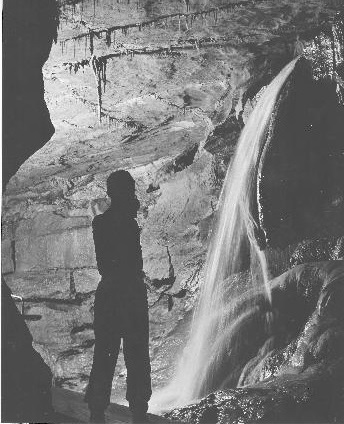

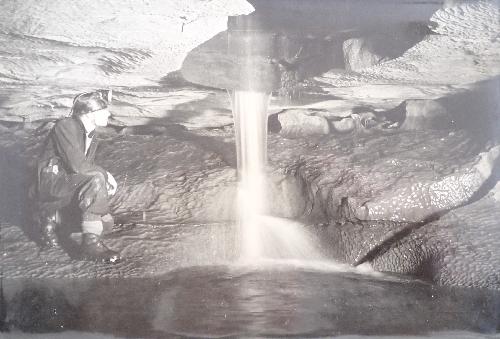

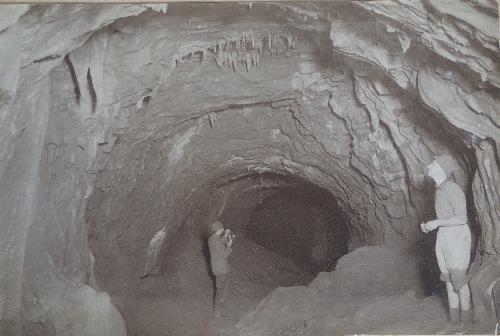

Early in his caving career Jack developed an interest in photography. He soon became an expert in this unforgiving discipline. In those early days the flash bulb had yet to come into common usage and the scene was usually lit with flash powder. A problem in enclosed caves was the amount of smoke this produced. There was normally only one chance at getting the shot before having to pack up and move on to another less fogged area of the cave. A popular brand at the time was described as ‘Smokeless Flash Powder’ but it was often unreliable, so it quickly became known to cavers as ‘flashless smoke powder’! Many of the classic monochrome prints Jack produced, from the late 1940s and early 1950s, in this way will be familiar to cavers, even today. Most of the images in the Underground Adventure book are his work. (The maps and cave surveys were drawn by fellow NPC member Arthur Gemmell, who was an architect by profession.)

However, not all of Jack’s early photographic endeavour ran smoothly. He once famously experimented by producing his own ‘improved’ flash powder, whilst still living at Heaton (Bradford). Whilst grinding magnesium and other ingredients in a pestle and mortar he caused a huge explosion. It brought the ceiling down, blew out a window and the flash was seen from as far away as the other side of Bradford. Later, in the casualty department and half concealed by burns dressings, Jack was chatting with the occupant of the adjacent bed and enquired why he had been admitted. His fellow patient explained he had been batting in a cricket match when he’d been distracted by a blinding flash, followed by a loud bang across the valley. He’d looked up and was then hit in the face by the cricket ball! I suspect that Jack never confessed his misdemeanour to that poor chap.

By his early thirties Jack had emerged as a leading figure in the caving world and was enjoying equal success academically. Everything seemed to be going well for him but then disaster struck. In 1959, shortly after attending a geophysics conference in Krackow (and one year after receiving his doctorate) Jack was struck down with polio. It left him physically weak, permanently confined to a wheelchair and seemingly with no real prospect of continuing with all the activities in which he had previously excelled. Senior NPC members still speak of shock and horror as the news spread through the club that Jack had become a victim of this terrible, incurable disease. But even those who knew Jack well were staggered by his resolve and determination to get on with life, after a lengthy convalescence and rehabilitation.

It was not long before he was out in the fresh air again, at the controls of a four wheel drive Haflinger on difficult terrain around the Dales. There were hair raising tales from fellow NPC members Cyril Crossley, Brian Heys and Rocky Holden, who would accompany him on these wild adventures. Next came a smaller three-wheeled Honda all terrain bike, which opened up further possibilities. Jack still drove on the road for many years and he designed and built a lightweight wooden ramp complete with electric winch to load and unload the Honda into the back of his shooting brake car. Many expeditions followed, at first around the nearer part of the Dales, then further afield to Swaledale and the Lake District.

He was often joined by another long term NPC member, Jim Leach (of Leach & Burgess, the well known former plumbing and electrical business). As Jim’s health failed in later years, he had also acquired a three wheeler, under Jack’s guidance. They would be accompanied by any number of NPC members, one of whom was Malcolm Riley of Giggleswick (a familiar figure on his mobility scooter around Settle until he passed away recently). The many trips which these folk embarked upon allowed Jack to develop his photographic interests in a different direction; he became admired for his landscape portraits and wildlife imaging. Many of Jack’s old friends, including me, still have examples hanging on their walls.

The NPC has had a number of members with disabilities over the years but this never seems to be a barrier to everyone getting out together and enjoying themselves. Inevitably, the possibility of Jack being helped to visit some of our more accessible caves was discussed and thus, once again, the Dales’ cavescapes came under the scrutiny of his lens. There is a tale of an evening trip into Kingsdale’s Yordas Cave via the bottom entrance, where Jack wanted to photograph the large chamber. A team was hurriedly assembled and off went the jolly party. Getting Jack back out of the cave afterwards, up the slippery mudbanks, was no easy task. As the mud-splattered team emerged from the entrance, tired and breathless, another caving party was met, with shiny new equipment betraying their inexperience, on their way to do an “abseil through” trip down the waterfall shafts from the top entrance. The first to emerge with Jack’s group, hauling on the end of the rope, was a teenage Michael Burgess (still in his school uniform from earlier in the day). Next was Pat O’Connell, still in bib and braces having come straight from work at Hopley’s builders. He was followed by Peter ‘Chester’ Shaw, who was best known for having only one leg. Jack then made his triumphant exit in the wheelchair, with an ageing Brian Heys pushing from behind. Whilst the “proper” cavers were trying to recover some sort of composure after witnessing this spectacle, the NPC party left the scene with the final words: “Aye, and we had a hell of a job getting him into the top entrance and down all the shafts!”.

Jack continued his association with the University of Leeds, long after retiring in 1982. He was still marking examination papers well into his seventies. He also diversified his academic interests by involvement in archaeological research, where his great love and skilful interpretation of aerial photographs proved invaluable. Even in old age Jack remained fiercely independent. He had problems with his teeth and often took a taxi to his preferred dentist in Otley. He would shuffle across the pavement and up a flight of stairs on his special home-made ‘bum protector’ (his words!) to gain the first floor.

It was only with great reluctance that he eventually faced up to the prospect of vacating his beloved Austwick to live in Steeton Court Nursing Home near Skipton, where he was very well cared for in the final stage of his life. I spent many an afternoon with him in his tiny room there. He would rock gently backwards and forwards in his wheelchair, in frustration at no longer being able to take part in the sharp end of cave exploration. But I always sensed his pleasure in being able to help guide us younger club members by generously passing on the great wealth of knowledge he had amassed during his incredible life. Having been an NPC member for six decades and serving the club as a trustee for many years, he was very proud to be elected as Vice President and he held this post until he died.

Jack passed away, peacefully, on 14th September 2008. The large number of cavers, academics and many Dales folk attending his funeral at Skipton Crematorium bore witness to the high regard in which he was held, despite having been forced out of mainstream caving by his cruel affliction almost half a century previously. He will best be remembered for his academic brilliance, his astounding determination in adversity, the unfailing help and support he gave to his many grateful students and for the legacy of many magnificent cave discoveries in the Yorkshire Dales for others to enjoy.

The tale of this unique man doesn’t end there, however. A few years after Jack’s passing, I was having an idle conversation with Dave Haigh, a caving friend. Dave is a long term member of the Bradford Pothole Club and we became engaged in an enthusiastic discussion about how the Underground Adventure book had inspired both of us, as youngsters, to become cavers. Then Dave mentioned that he’d been thinking of trying to write an updated version of Jack and Arthur’s 1952 book. He hadn’t realised how well I’d known Jack until that conversation and he asked if I’d be interested in writing a chapter for the book. So I did; Dave liked it and, to cut a very long story short, I increasingly became part of a project that I wouldn’t have missed for all the world.

The result is our own book “Adventures Underground” [3] which was published in April 2017. It follows a theme similar to the original 1952 book Underground Adventure but with the exploration of the many cave systems brought up to date. Jack was greatly respected within the caving community (as indeed was Arthur, his co-author) so we received generous help in many ways from a large number of caving friends. We therefore decided to give all the royalties to two charities, being divided equally between Macmillan Cancer Support and cave rescue. The book seems to have been well received by cavers and also by those outside the caving community; it has sold well and we have had the great pleasure of passing on substantial sums of money to our chosen charities as a result. The icing on the cake for us came in September 2018 when we won that year’s national award for caving literature. If I could have one wish granted, it would have been for Jack and Arthur to have seen our recent book before they passed away. Dave and I look on it as our best shot at a tribute to these two great men; I like to think they would have been pleased.

A lot of Jack’s large collection of caving material was passed to the Northern Pennine Club by his executors, for safe keeping. However, much of it is regarded as having national importance, far beyond just his own club. As I type there is a great deal of work being undertaken to scan Jack’s personal and other records. This is a joint project between people involved with the British Caving Library and a British Geological Survey archivist. It is likely that all these scans will be made available online, probably as an annexe to the BGS website, thus providing the best possible access for anyone interested. We are hoping that this resource will go live (and thus be flagged up by online search engines) by the time the above article is published in this journal.

Acknowledgements:

I’m indebted to Chris Howes, for help with some of the photographs for the above tribute. The text is a much amplified version of a shorter article, which was originally written in 2008 for the cavers’ magazine Descent [4]. Several friends or members of Jack’s family helped at the time by providing information or by checking on facts. I’m particularly grateful to Bert Bradshaw, Joan Butler, Cyril Crossley, Dave Gibbon, Joe Mather, Helen Pickersgill, Malcolm Riley and Peter ‘Chester’ Shaw. Sadly, some of these have passed away since I wrote the original text; their support and generous assistance is not forgotten.

References:

- Gemmell A & Myers J O, 1952, Underground Adventure. Dalesman Publishing Company (Clapham, N.Yorks.) with Blandford Press, Ltd. (No ISBN.)

- Gemmell A & Myers J O, 1990, Underground Adventure (reprint). Mendip Publishing, Castle Cary Press, Somerset. ISBN 0 905903 19 6.

- Haigh D & Cordingley J N, 2017, Adventures Underground. Wild Places Publishing, Abergavenny. ISBN 978-0-9526701-9-3 (softback edition).

- Cordingley, J N, 2008, A Speleologist and Man of Iron. Descent 205 Dec/Jan 2008/09, pages 30-31.

Jack Myers in Gunnerfleet Cave (early 1940s

Jack Myers (1948

Dr Bannister’s hand basin’, Upper Long Churn Cave (late 1940s

Sleets Gill, Littondale (1942)