| JOURNAL 2022 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

This project was carried out as a MA Heritage Placement at Lancaster University Department of History with a bursary funded by NCHT.

Introduction

In the North West the main ports involved in the trans-Atlantic slave trade were Liverpool and Lancaster, some seventy and thirty miles respectively from North Craven. During the late eighteenth-century North Craven was primarily a rural district, relatively sparsely populated and with most occupations associated with agriculture and the textile trade. So it would be natural to assume that there would be few links with the slave trade. However, my research soon showed that there were individuals whose business was concerned with the slave trade in Liverpool and Lancaster, and who had links to or owned property in North Craven.

Knight Stainforth Hall

This house (Fig 1) is an imposing three-story building with six bays and whitewashed exterior and dates from the late seventeenth-century. In 1689 it was owned by Samuel Watson, an active Quaker and member of the Giggleswick School Board. It was then purchased from Watson by Christopher Wetherherd before the former’s death in 1708 as detailed in Wetherherd’s will of 1732.‘First I give and devise to my son John and his heirs for ever all that my capital messuage and tenement at Knight Stainforth aforesaid with all lands closes pastures hereditaments and appurtenances there unto belonging and all that water corn mill thereto also belonging (all which I purchased of Mr Samuel Watson deceased) on condition that my said son pay to my dear and loving wife the yearly sum or annuity of £10 over’ [1]

The remainder of the will goes on to divide the estate between Wetherherd’s four sons, their descendants, his wife, and their employees. No further documentation exists for the John Wetherherd mentioned in this will, but it can be supposed that due to his receiving the bulk of his father’s estate he was likely to have been the eldest child, and that after his death ownership would be passed on to his nearest surviving relative. Certainly, the next evidence of ownership comes some 46 years later, not from John, but from another Christopher, and gives insight into not only the financial situation of the Wetherherd family, but also into their current business ventures outside of the county of Yorkshire, and indeed, outside of England altogether, and halfway across the world to the slave ports of Africa and plantations in the West Indies [2].

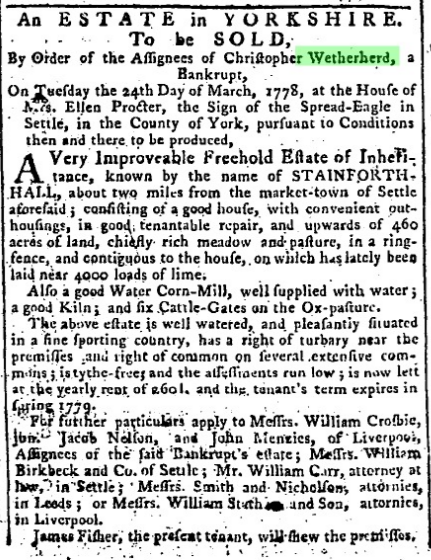

Figure 2 shows a newspaper article from 1778 detailing the notice of sale for Knight Stainforth Hall ‘By Order of the Assignees of Christopher Wetherherd, a Bankrupt.’, and reveals the sale of the house, alongside all accompanying outhouses, together with 460 acres of land and one cornmill. Furthermore, one un-referenced source of the history of Giggleswick states that in addition to his North Craven estate, Wetherherd also owned property in the West Indies, and quotes the source as listing for sale ‘tropical plantations in Dominica and Tobago’ alongside ‘all those negroe Slaves following: that is to say, Venture, Mail, Somersett, Industry, Cato, Derry, Lidia and her child, Exchange, Kenzie, Mary, Ann, Joan, Catherine, Aurelia, Phebe, Hannah, Marge, Tom, Diligence, Jolly, Jenny, Margaret, Belinda, Dine and the future increase of the Females of all such slaves.’ [3] Try as I might I was unable to pin down this source, which unfortunately remains unconfirmed. However, if correct it indicates that Wetherherd owned multiple plantations in the West Indies, alongside numerous slaves and their children.

A marriage certificate dating from the ninth of September 1774 for Christopher Wetherherd and Mary Audley is one of the first existing records available for Wetherherd, describing him as a 30-year-old merchant, and Audley as a 21-year-old spinster who were married in the parish of Liverpool. Wetherherd’s age of 30 in 1774 places his date of birth in 1744 but gives no indication of place of birth or any further heritage. An inspection of the Slave Voyages database lists several name variations for Wetherherd, including C Weatherhead, C Wetherhead and Chris Wetherhead, as vessel owner on eight slave voyages from 1766 -77, all sailing from Liverpool, and listing various places of purchase, from Cape Mount, Gabon and New Calabar, to slave landing ports in Jamaica, Dominica, Tortola, and St. Kitts. Each journey conducted by Wetherherd’s vessels carried an average of 200 slaves, around a fifth of whom were expected to perish on the journey.

Indeed, the journey of the ‘John’ sailing from Liverpool via New Calabar to Dominica in 1775, financed by Christopher Wetherherd, picked up 352 slaves, of whom only 287 made it to their destination. One of the reasons for the high mortality rate was the terrible living conditions endured by those on board, with overcrowding, together with dark, damp, inhumane conditions and poor diet making disease rife and deaths inevitable. One piece of data from this same voyage highlights not only the extreme conditions these individuals had to endure on these journeys, but also the greed of the ship captains and vessel owners, together with their disregard of the lives of the individuals on board. According to data, the number of slaves intended to be collected at the first port in New Calabar was 250, however, as already stated, the final number of slaves totalled 352 which was 152 more than planned. This type of extreme overcrowding was common on slave voyages, with ships routinely picking up more individuals than was safe, firstly to offset the inevitable number of deaths during the voyage, and secondly because a greater number of slaves meant a greater amount of money on arrival at the destination port.

1765 marks the first slave voyage listing Wetherherd as vessel owner, with the Commerce leaving Liverpool and making its way to Gabon, before sailing on to Tortola, an island in the West Indies known for its sugar-cane industry, with large plantations dependent on slave labour from Africa. Figure 3 details locations in Africa which constituted the main sources of slaves for traders from Liverpool, together with the routes taken across the Atlantic and the major slave landing ports and countries. Documents suggest that the Commerce departed Liverpool on August 2, 1765, and arrived in Tortola on November 24 the following year. Of the 150 slaves collected in Gabon only 82 disembarked. In contrast to his later voyages for which Wetherherd is listed as the sole vessel owner, the registration documents for the Commerce list three additional owners alongside Wetherherd, including Charles Lowndes, possibly a relation of Francis Lowndes, a former tobacco merchant from Liverpool, William Brock, probably Brocklebank, another frequent investor, and George Rishton. It was not unusual for investors, particularly when just starting out, to opt for part-ownership of vessels, often clubbing together with friends or fellow merchants to finance voyages together.

Upon Wetherherd’s bankruptcy in 1778, Knight Stainforth Hall was purchased by Thomas Backhouse, another slaving merchant from Liverpool and possibly a member of one branch of the large Backhouse trading family from Ulverston. Born in 1754, Thomas was the son of John Backhouse, also a slave merchant, hailing from Milnthorpe, a small trading village on the now unnavigable far eastern tip of Morecambe Bay. Thomas, it seems, was an even bigger slaving merchant than Christopher Wetherherd, investing in at least 17 slave voyages, including some joint ventures with his brother and father, both named John, and one joint voyage with Daniel Backhouse who was one of the biggest slave traders in Liverpool and possible relation of Thomas. A large portion of the voyages funded by Backhouse focused on ports in Benin and neighbouring Bonny (modern day Nigeria), with places of landing listed as Dominica, Tortola, St Lucia, Havana, and Kingston.

The first slave journey listing Thomas Backhouse as owner dates from 1779, where he is listed alongside John Backhouse, William and Charles Pole, Henry Gardner and William Rutson, as part-owner of Tartar’s Prize, which carried 692 slaves from an unspecified port in Africa to Jamaica. Unlike Wetherherd, Backhouse never ventured into sole ownership of any slave ships, always opting instead for joint-ownership, often with the same individuals. The next two slave journeys financed by Backhouse took place in the following two years and both ended in disaster; the Sarah in 1780 was listed as ‘shipwrecked or destroyed before slaves embarked’, meaning that it was wrecked on its journey between Liverpool and Africa, whilst the following year the Falstaff was captured by the French, again before reaching Africa. Losses like this would have cost ship-owners such as Backhouse dearly, and perhaps goes some way to explaining why he and many of his fellow merchants often chose to opt for part-ownership instead of full in order to lessen the damage to investments.

During the ownerships of both Wetherherd and Backhouse, Knight Stainforth Hall probably remained a country retreat, with neither gentleman using it as a full-time residence, and instead choosing to remain where much of their business took place and from where their ships sailed, Liverpool. One record from 1781 places Christopher Wetherherd as living at 31 Tythe Barn Street, Liverpool, just a stone’s throw from the docks. Figure 4 shows a map from 1819 pinpointing an approximate location for Wetherherd’s house. Thomas Backhouse and his brother John, meanwhile, owned property at 11 Duke’s Street, located in a similarly central location near the Liverpool docks.

Christopher Wetherherd died on September 8, 1800, with a will from the time stipulating that ‘Mary Wetherherd…lawful widow of (Christopher Wetherherd)…are holden and firmly bound unto the Right Reverend Father In God Henry William…in the sum of three thousand pounds …to be paid to the Right Reverend Father,’, indicating that at the time of his death Wetherherd was still in debt after his bankruptcy. Thomas Backhouse had died in 1795 at his home at Beck House in Giggleswick which he had purchased some ten years after Knight Stainforth Hall. The latter, upon Backhouse’s death, passed to his widow Jane, during which time it seems it was occupied by tenant farmers. Thomas’s brother John, however, carried on trading in slaves almost up to 1805, just two years before the law made the trade of slave illegal in Britain. Upon Jane’s death sometime between 1734-39, ownership passed to the Maudsley family, and Knight Stainforth Hall finally ceased all association with the slave trade.

Conclusions

The histories of individuals such as Wetherherd and Backhouse are rarely told, holding as they did comparatively minor roles in the wider trans-Atlantic slave trade, particularly in relation to other more prominent slave trading families. However, no role played by any individual in the enslavement of black Africans is too small to tell, and it is a sobering thought that the financial input from just one individual such as Wetherherd or Backhouse could immeasurably change the lives of potentially hundreds of other individuals.It would be interesting to find out more about Wetherherd’s plantations in Dominica and Tobago. Nothing is known of the fate of the 25 slaves mentioned in the fragment of Giggleswick history, and this would be an interesting line of enquiry for further research.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Nick Radburn of Lancaster University, Pamela Jordan, Mike Slater, and additional members of the North Craven Heritage Trust for their support and patience during the course of this project.

References and further reading

- Giggleswick Wills and Invents 1702-1750, available from: http://www.northcravenheritage.org.uk/NCHT/NCHTWebWills/WillsInvList3.htm

- No documentation exists detailing the relationship between the Christopher Wetherherd from 1732 with the later Christopher Wetherherd from 1778, however, the fact that Knight Stainforth Hall passed directly to Christopher via John suggests they were direct relations, very possibly grandfather and grandson.

- Legacies of British Slavery, “Profile of Christopher Weatherhead/ Wetherherd,” n.d., https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146644625.

A Plan of Liverpool with part of the environs, J.Gore, (Liverpool, 1819), Bibliothèque Nationale de France, available at: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b8441341f/f1.item.r=Liverpool.zoom

Atlantic Slave Trade Map, 2013, available at: https://billygambelaafroasiaticanthropology.files.wordpress.com/2013/11/trans-atlantic-slave-map.gif

“An Estate in North Yorkshire to be Sold” General Evening Post, March 12 - March 14, 1778. Seventeenth and Eighteenth-Century Collection Burney Newspapers. Available at: http://link.gale.com/apps/doc/Z2000455794/BBCN?u=unilanc&sid=bookmark-BBCN&xid=3888130f. Accessed 11 Oct. 2021.

Giggleswick Wills, accessed via North Craven Heritage Trust Archives, available at: http://www.northcravenheritage.org.uk/NCHT/NCHTWebWills/WillsInvList3.htm

John S Turner, Knight Stainforth Hall, Little Stainforth, photograph available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Knight_Stainforth_Hall,_Little_Stainforth_-geograph.org.uk_-_433550.jpg

Legacies of British Slavery. “Profile of Christopher Weatherhead/ Wetherherd” n.d. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/lbs/person/view/2146644625.

Richardson, David, Suzanne Schwarz, and Anthony Tibbles. Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. Book. 1st ed. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2007.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3