| JOURNAL 2022 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

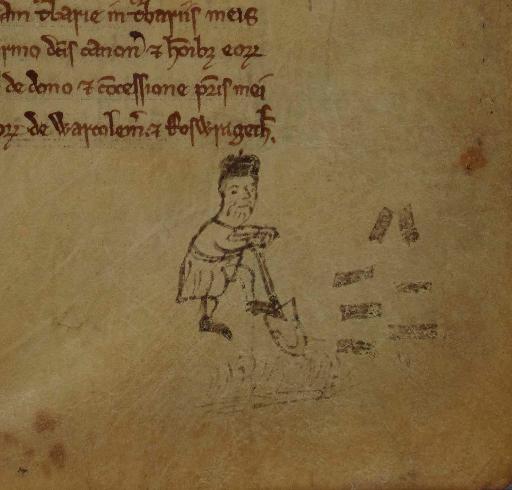

As the interlocking complexities of climate change unfold before our eyes, we seek that clarity of vision that comes from a close association with the land down the ages. Helen Wallbank admirably displays her own familiarity and close association with the land in the Hodder Valley throughout her publication and most importantly dispels the myths which surround the random artificial boundaries created by local authorities in today’s world. In her introductory chapter, she describes the strong links between the Hodder Valley and the Craven District just over the watershed. Peat- the more widely used term for turf – was a vital source of fuel from monastic times and very much earlier. The ability to create fire for warmth, cooking and other essential uses represented a major landmark along mankind’s road to civilisation. In the medieval period, much of the land in our area was granted to monasteries and priories, among them Sawley, Furness, Fountains and Kirkstall, with their agricultural activities managed by lay brothers. A delightful 14th century marginal illustration of digging and stacking peat from the Cartulary of Lanercost Priory near Carlisle, shows one of the brothers hard at work (Fig 1).

The terminology and implements relating to peat extraction is also of great interest and provides further clues to its origins and geographical range. There are clearly both Scandinavian and Anglo-Saxon influences. As Helen points out, peat/turf ‘dales’ originate from the Old English word for share ‘dael’, indicating that the strips were divided amongst households and succession rights passed down to individual properties rather than named individuals. These ‘daels’ were often marked out on the ground with numbered stones and the approach routes to the sites were named ‘turbary roads’. Modern maps provide a good indication of where peat beds were and still are to be found. If you see the place name ‘Moss’ you can be pretty sure this will provide the ideal environment for peat. Spades were of different patterns, deriving not only from their uses but also according to the blacksmiths who made them. The typical Ribblesdale peat spade, also used in the Hodder Valley, bears a striking resemblance to a spade from Denmark, indicating the influence of Viking-age settlers in our upland areas.

A deep understanding of the need for the proper care of peat and turf as valuable resources and their preservation for future generations emerges very strongly from the descriptions given about individual sites. Continuity is key and the requirement to limit digging to what was required for domestic rather than commercial purposes, together with the desire to ensure that peat banks remained properly hydrated in order to encourage new growth, was clearly appreciated from the earliest times. It is interesting to note therefore that regeneration schemes, which acknowledge the unique capacity of peat to store carbon, have been introduced and implemented in our area for at least the last ten years by organisations such as the Bowland AONB, the YDNP and the Yorkshire Peat Partnership - another example of the importance of creative local knowledge at work.

Helen Wallbank has packed an impressive amount of information into this beautifully illustrated booklet and provided future researchers with the means of pursuing a range of further approaches to the subject from many different angles. At the end of each section she has listed her sources with meticulous care – a feature often sadly lacking in other such publications. Helen shows the importance of bringing together evidence gleaned from legal documents, such as wills and inventories with diaries and oral histories, coupled with close personal observation.

This gem of a publication makes for compulsive reading and I wholeheartedly recommend everyone to acquire their own copy in order to gain a wider understanding of so many aspects of our remarkable area.

Fig 1 Courtest of Andre Berry, Natural England