| JOURNAL 1992 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

It is very difficult to know what local furniture styles were like in the 18th century and before. Very little furniture in houses other than those of the aristocracy has survived unmoved and documented since the eighteenth century. It was only in the case of clocks that the practice arose of a maker signing his work with his name and place of business. The eighteenth century clock makers only made the movement themselves and usually left their customers to commission the making of the wooden case which held the clock. Naturally, many customers arranged for local cabinet makers to produce a case for their clocks. After seeing a number of the cases in which local clock movements have been housed, it is possible to state with a degree of certainty that a certain case is the work of a local cabinet maker, or alternatively that a clock movement has been "married" with a "foreign" case.

The Settle cabinet makers (the Hallpike and Harger families) evolved their own style of case, just as the clock makers evolved their own locally distinctive style of dial.

One of the best documented of the 20 or so clock makers based in Settle was Thomas Hargraves who lived 1741 -1813. Thomas Hargraves was one of a family of Settle clock makers. The documentary evidence which survives, shows him to have been of particular interest both socially and to the student of horology.

As can be seen from the accompanying family tree, Thomas was the son of William Hargraves I, who was also a clock maker in Settle. William I produced some of the most sophisticated and interesting Settle-made clocks which have survived. As well as one handed and 30 hour clocks, typical of the early 18th century, William I is known to have produced two handed 30 hour clocks, 8 day clocks, and a clock which every fourth hour, immediately before striking the hour, plays 2 verses of a hymn tune on 6 bells.

William I was almost certainly a descendant of the Hargraves family which lived at Deepdale Head in Wigglesworth. Our difficulty in being certain is due to the fact that William I and his wife were Quakers, and documentary references to them are scarce.

However, we know that he married a girl called Elizabeth and that by the 1740's he was living and working as a clock maker in Settle. In 1742, he mortgaged the house where he lived in Settle Market Place to a Bradford based butcher named Henry Barrowclough. His house had 3 rooms on the ground floor with 2 attic rooms over, with 2 work rooms and a smithy with a room over them adjoining. In addition, there was a pig sty, half a stable and a pair of balkes over that (i.e. a hay loft), the whole of which was mortgaged to secure £60 plus interest. The witnesses to the document strengthen the likelihood that William Hargraves I was a close relative of the Deepdale Head Hargraves family.

Understandably, his son Thomas Hargraves was brought up as a Quaker. However, this was not to continue. In 1765, at the Settle Quakers monthly meeting, 13 Quakers signed a Paper of Denial which read as follows: -

"Whereas Thomas Hargraves, a young man who was brought from his childhood in the attendance of the religious meetings of the people called Quakers and since he came to years capable of religious consideration having frequented the same was thereby looked upon as one of our society; but for want of due regard to the light which enlighteneth every man that cometh into the world teaching to shun the appearance of evil he hath suffered himself to be led aside to commit that which is shame to himself and a reproach to the society he was reputed a member of and has married a wife of different persuasion by a priest which is also contrary to the known rules established amongst us; wherefore the clearing of truth we can do no less than testify against such practices and hereby publicly disown him to be a person in religious unity with us until by a circumspect life and conversation he show forth true repentance which that he may do so is our sincere desire".

The action which prompted such a document was the fact that on 24th November 1764, Thomas Hargraves had married Sarah Sergeantson, the daughter of a local wood comber, John Sergeantson of Settle, at Giggleswick Church. In those days, to marry outside the narrow band of the Quaker fraternity was punished by expulsion from "friendship".

For a time, Thomas Hargraves's religious principles must have caused some struggle with his conscience. It took him the best part of 7 years to decide that he could no longer be reconciled with the local Quakers. Then on the 3rd April 1772, at the age of 31, he was baptised at Giggleswick Church. His oldest son William, had been baptised on 15th March in the same year.

One does not like to be cynical, but it was in the same year that the Giggleswick churchwardens' accounts show that Thomas Hargraves was to have a commercial interest in the established church: -

"Agreed by the four and twenty [a body of notable parishioners] that Thomas Hargraves is to have five shilling per year for keeping the clock in proper repair. Also that John Higson is to have 10 shillings per year for keeping the dogs out of the church and keeping the doors shut".

Despite Hargraves's technical expertise, the local churchwardens clearly valued the practical experience of John Higson more! In the meantime, it is clear that Thomas Hargraves's in-laws were supporting him. For £5 of lawful English money his father-in-law John Sergeantson sold him a dwelling house, barn, cow house, turf house, orchard and rights of turbary in the Gallaber turf pits with all other incidental rights on 29th November 1766. Given the recent marriage, this looks like Sergeantson giving his new son-in-law a helping hand financially.

The records of the late 18th century in Settle are scant. There are a number of references to Thomas Hargraves buying and selling land in or about Settle. In the 1780's and 1790's, Thomas Hargraves was being assessed to land tax on land in Settle and at Stockdale, where interestingly enough, another Hargraves family retained a landed interest for almost a century after that time.

Many Thomas Hargraves I clocks survive from the late 18th century, which is an interesting time in the history of clock making. About the year 1775, brass dial clocks were rapidly superseded by white dial clocks. The dials were manufactured in Birmingham to the order of local clock maker. Later, clock makers ceased to manufacture the movements and instead relied upon mass produced movements which were also bought in from the Midlands. Thomas moved with the times and produced clocks with the modem white dials, but seems to have continued to make his own movements.

Thomas Hargraves continued to be a prominent local businessman. In the papers of the Birkbeck family of Anley (themselves a prominent Quaker family) there are references to buying brass hinges from Hargraves, which can only be a reference to Thomas Hargraves indulging in other brassworking activities.

In addition, the Birkbeck archive gives us an interesting insight into a petty feud in which Thomas Hargraves was involved in 1785. The problem concerned young Joe Eglin who was an apprentice to William Birkbeck, a draper and the post master of Settle at the time. Joe Eglin wrote to his father to say that last Sunday he had been going about his master's business (i.e. delivering letters) when he came across a local tradesman with whom there had long been a festering quarrel. The tradesman, none other than Thomas Hargraves, threatened to knock the apprentice's teeth down his throat and announced that "I'll have thee my lad" to which Joe Eglin nervously laughed. Eglin admitted to his father that he "once stooped with an intention to take up a stone to throw at him, but did not do it though when I rose up I spit at him to show (though not upon him) I considered him as not worth my while being in a passion at".

This incident caused Eglin to write home to his father to request that his father would lay a complaint against Hargraves before the Magistrates because he was in terror of Hargraves, whom he described as a fellow "as would stick at nothing to gain his end".

In fairness to Hargraves, Eglin's own father was not 100% on his son's side. Eglin senior had received a letter from Thomas Hargraves's older brother (William II) as well as one from his son, which had alerted him to where the rights and wrongs of the dispute might lie. His son may have been wronged, but he also had to bear a share of the blame:

"Although the man has acted very unbecomingly and altogether improperly yet I can not by no means excuse my son of disreputable conduct. Therefore I must desire (if they think there is no danger to be apprehended from him in future) to stop all further proceedings and what expense already occurred then will please pay on my account. If the misunderstanding between them has rose from the Gun and TH has thought himself a sufferer in not being sufficiently paid for the damage he did to it, I could wish him to be satisfied".

Thomas Hargraves made his will on Christmas Eve 1813. He described himself as being a watchmaker. It bears witness to both the wealth which he had generated through his activities and the technical expertise which he had built up.

After leaving £325 in cash to his children, sister and niece, he left his son William Hargraves II his gold watch with a seconds pointer and to his daughter Catherine Matthews his gold hunter's watch. He left his "time piece" to his son Thomas II. This was almost certainly a superior quality long case clock which kept very accurate time for the purpose of regulating the other clocks which he made. He left his clock maker's tools to his two sons Robert (who worked in Skipton) and Thomas II (who subsequently worked in Settle) and then made his son Thomas II the sole executor of his will.

Thomas Hargraves I was buried on 1st January 1814 at Giggleswick Church. His son Thomas II lived on until 1835 and was also buried at Giggleswick, in a grave with his son William III, also a clock maker.

Thomas Hargraves was a prolific clock maker; many of his clocks survive to the present day. They are good time pieces and many of them are in extremely attractive and locally made cases. They are typical of the product made locally, but, with our knowledge of the man who made them, have an extra fascination for the collector interested in purely local furniture and artefacts.

J1992p10_19_files/tmp9A5-4.jpg

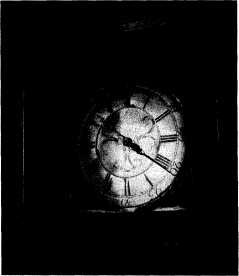

Clock face by Thomas Hargraves of Settle (photo by Mary Farnell).