| JOURNAL 1993 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

It would probably be wrong to suppose that the story of the Ingleton Coalfield is history. Coal still remains in the ground beneath Ingleton and over the decades, or perhaps centuries to come, technology or economic expediency will find a way to exploit it. Indeed, the next chapter in the Ingleton Coalfield story may be just around the corner, if coal bed methane really is the fuel of the future as some geologists now believe.

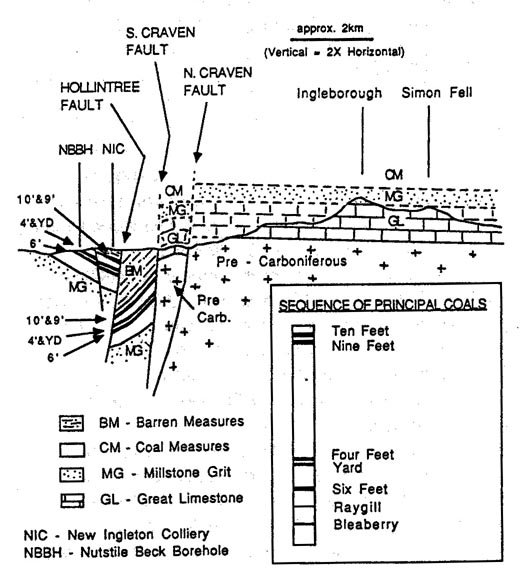

Ingleton is lucky to have had a coal-mining history at all. Mineable coal occurs in Britain in relatively thin seams (up to 14 feet thick) within what is known as the Coal Measures. Geologically, economically useful Coal Measures are sandwiched between the underlying Millstone Grit and the overlying Barren Measures, and they in fact consist mostly of sandstones and shales rather than coal. The thickest coal measures in the country occur in the Lancashire-North Staffordshire Coalfield, where they are up to 3 km thick. Both in this and the North Yorkshire Coalfield, the best coal is to be found in a seam which miners call the "Barnsley" or the "Top Hard" seam, more or less in the middle of the Coal Measures sequence, although in these fields coal is also extracted from numerous other seams. The Coal Measures of the Ingleton Coalfield attain a maximum thickness of less than 400m and represent only the lowest part of the British Coal Measures succession, the upper part having been eroded away prior to deposition of the overlying Barren Measures. Being so thin, the Ingleton Coal Measures do not include the Top Hard seam, so that Ingleton mining had to rely on the presence of other, nonetheless high quality, coal seams.

The earliest mines of the Ingleton Coalfield (dating back to the early 1600's) are to be found along the banks of the river Greta, where three seams outcrop at the surface. Of these three, by far the most important economically were the "Four feet" and "Six feet" seams (names which refer to the seams' thickness rather than to their depths of burial). Between these two seams occurs a third, inferior, seam known as the "Yard seam". The coals from the different seams were of different qualities, so that the Four feet coal was used for domestic purposes whilst the Six feet coal was found to be more suitable for industrial use. The thickest seams of all in the coalfield were in fact to remain undiscovered until the sinking of the New Ingleton Pit in 1913. Quite by accident, and to the undoubted glee of the mine owners, during excavation beneath the base of the Barren Measures cover sequence the mine shaft penetrated a Ten feet and a Nine feet seam. These seams, the youngest in the coalfield, do not outcrop at the surface, having been truncated by erosion prior to the deposition of the Barren Measures (see figure 2) but are now believed to underlie much of the area covered by the Barren Measures (see figure 1).

The earliest demand for Ingleton coal predates the industrial revolution by about a century, and was driven by the needs of local textiles and potteries industries, and from export of coal to the surrounding area for domestic fuel and lime burning. The raw material for lime burning was the limestone sequence overlying the barren measures, whilst some of the best potters' clay is extracted from the fossilised soils which sit directly beneath coal seams, the so called "seat earths" on which the coal swamps grew. Coal and iron were the raw ingredients for the industrial revolution, but Ingleton had no iron ore, and it is true to say that the Ingleton Coalfield prospered in spite of the industrial revolution, supplying an isolated region with relatively expensive coal. The situation changed with the opening of the railway in the 1840s, linking the Ingleton industrial infrastructure with the more economic coalfields to the south. At the acme of the coalfields in the 1830s up to 16,000 tons of coal were produced a year from one of the principal collieries, the Ingleton colliery. This was burned to provide about half of the power required by the local cotton mills at Bentham, Ingleton and Burton, the remainder of the power being supplied by waterwheels. Comparing the Ingleton colliery figure of maximum production with a figure for Britain as a whole at the same time of roughly 60,000,000 tons per year gives an idea of the relatively small scale of production at Ingleton. To put that in wider context, Britain was producing around 300,000,000 tons of coal per year by the first decade of this century.

By the turn of the 20th century the general lack of demand for Ingleton coal combined with the fact that most of the relatively accessible coal had been worked out around the rim of the coalfield, meant that coal mining had effectively come to an end for Ingleton. By sinking the New Ingleton Pit in 1913, the directors of the then recently formed New Ingleton Collieries Limited Company were playing a game of "Big Risk—Big Reward" in which the risk was the geological uncertainty of discovering coals beneath a thick succession of Barren Measures, and the reward appears to have been trade with the shipyards in Furness, in North Lancashire. The company was spectacularly lucky in not only encountering the Four feet and Six feet seams at 700 and 800 feet respectively, but also prior to this in discovering the Ten feet and Nine feet seams. Surely only cheap labour or geologically naive (or brave) financial backers could have justified this undertaking. Despite this undoubted good fortune, the coals in this colliery were exhausted by 1936, with the miners encountering the Hollin tree fault at depth, a relatively short distance from the main shaft itself (see figure 2).

Given the political climate of the 1990s, and a government dedicated to ousting the miners' unions, where necessary by removing the workforce itself, it could be argued that we might have to wait a very long time before the next instalment of the Ingleton Coalfield story. Research in the Unites States during the past decade however has shown that one of the coal miners' most feared enemies, "firedamp", may represent a hitherto unsuspectedly rich store of coal energy resource. Firedamp, or coal bed methane as it is more properly known, is chemically much the same as North Sea gas, but whilst North Sea gas occurs naturally mainly in porous sandstone reservoirs, firedamp is natural gas which resides within the coal seams themselves. One of the main advantages of coal bed methane over North Sea gas is that it is much cheaper and less risky to drill wells in an onshore coalfield, whose geology is already well known, than it is to drill from an offshore platform into often relatively uncharted geology. The US now has over 200 working coal bed methane wells, the optimum depth of burial of coal reserves for production of gas lying in the range of 450 to 1000 metres—exactly the depth range of coals in the deepest part of the Ingleton Coalfield, between the Hollintree and South Craven faults.

Perhaps the tide has already begun to turn again for Britain's beleaguered coalfields. An American company, Evergreen Resources, of Denver, has already completed a 1000m deep well close to Liverpool, whilst a British company, Kirkland Resources, of Harpenden, holds exploration licenses for coal bed methane over much of the South Wales Coalfield. If coal bed methane becomes established as a cheap alternative to offshore natural gas it may not be long before it becomes economically viable to prospect for gas in the hitherto untapped deep part of the Ingleton Coalfield. A. Christian Ellis.

Sources:

Weighell, T. (1992) Making Money Mining Gas. New Scientist. No. 1841

Harris, A. (1965) The Ingleton Coalfield. In Industrial Archaeology, the Journal of the History of Industry and Technology. No. 5, November 1968

Ford, TAD. (1954) The Upper Carboniferous Rocks of the Ingleton Coalfield. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. Volume CX, pp231-265

Edwards, W. and Trotter, F.M. (1954) The Pennines and Adjacent Areas, pp vi + 86. HMSO London

Dunham, K.C. (1971) One Inch Geological Map of the Hawes area, Solid edition. (Sheet 50)

Diagrams drawn by the author.

J1993p10_20_files/tmpBB9-13.jpg

Mess with diagram

J1993p10_20_files/tmpBB9-14.jpg

Figure 2 - Cross Section of the Ingleton Coalfield, also showing the sequence of the principal named coals (inset). Coal seams within the coalfield are shown by heavy lines. Pecked lines denote strata which have been removed by erosion. Section based on British Geological Survey; Sheet SO, and Ford (1954).