| JOURNAL 1998 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

The Yorkshire Dales National Park's Archaeological Conservation Officer, Robert White, writing in the Heritage Trust's Journal for 1994, intimated that the Park would appreciate help in surveying and recording field kilns across the Park. He also briefly described the Local Historical Features Scheme which can provide grant aid, of up to 100 per cent, to consolidate and secure kilns of particular local importance. To date, the Park has funded work on six kilns under this scheme, and a further six under other grant aid. Further finance is to be provided from Millennium sources.

A full survey was carried out in the parishes of Sedbergh, Dent and Garsdale by members of the Sedbergh History Society, with their results being published in 1995.

The present writer undertook a survey of the kilns in seven parishes around Settle in 1996 and 1997. A full report, with photographic support, has been submitted to the National Park and a copy is to be deposited locally. This article is a summary of the report. It is not the intention here to discuss the use to which the kilns were put; that was adequately and concisely treated in White's article and in his recent book.

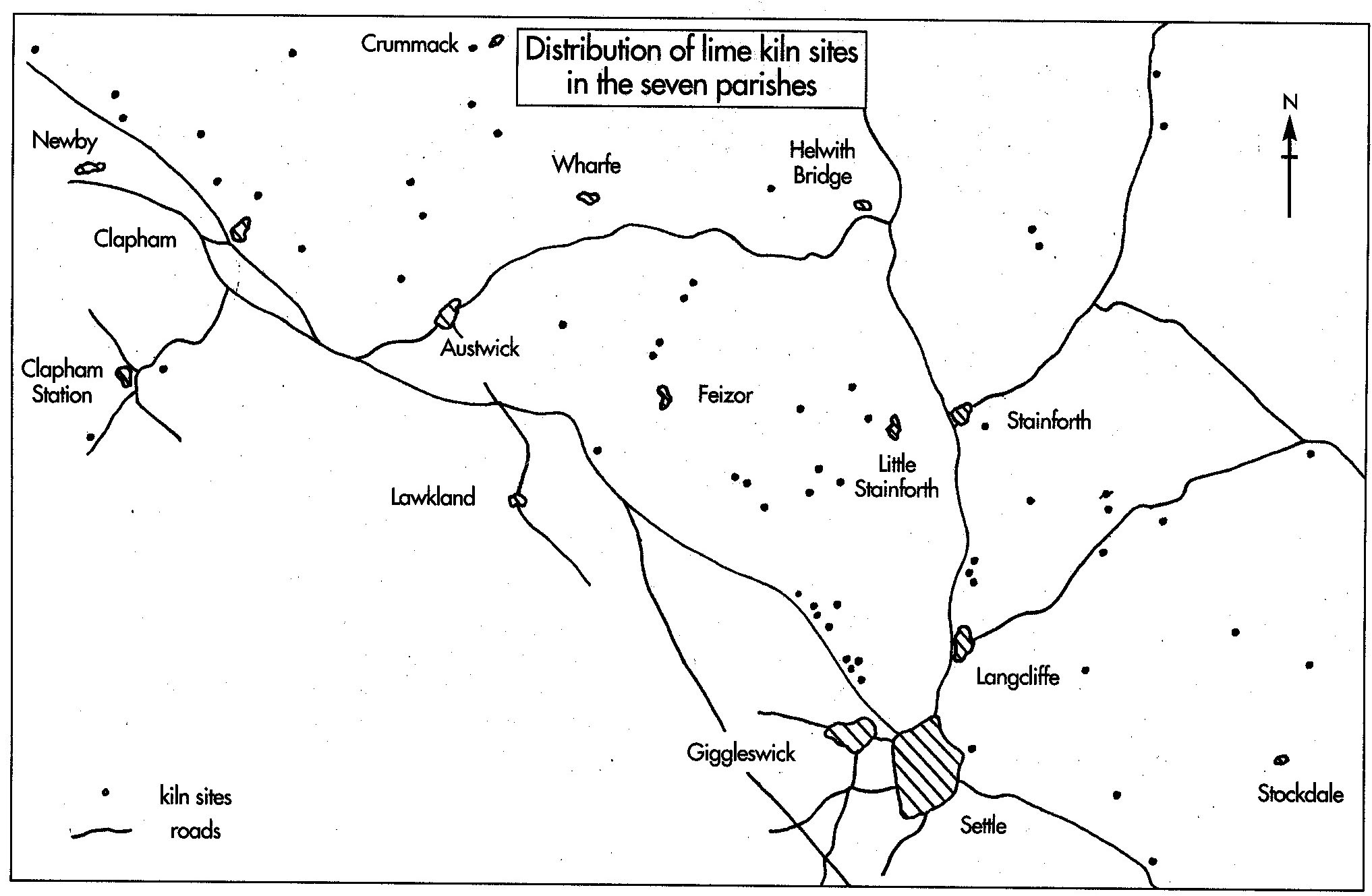

The survey area covered the parishes/former townships of Stainforth, Langcliffe, Settle, Giggleswick, Lawkland, Austwick and Clapham. A list of sites was obtained from documentary sources, and these sites were crosschecked with the various Tithe maps of the 1840s, and with the First Edition Ordnance Survey six inch maps, published in 1851. Each site was visited with the landowner's or tenant farmer's permission to carry out a full survey. This field exercise brought to light a number of kilns new to the record; in all 62 sites were identified and visited (Fig. 1). Thirty-four farmers or landowners were approached, the majority expressing interest in the study. Some were enthusiastic, and only one denied access to a kiln on his land.

Fig. 1

Distribution of lime kiln sites in the seven parishes

|

Parish |

No. of sites |

|

Stainforth |

11 |

|

Langcliffe |

9 |

|

Settle |

4 |

|

Giggleswick |

14 |

|

Lawkland |

6 |

|

Austwick |

8 |

|

Clapham |

10 |

Objectives

The survey was intended to make as full a record as possible. Basic site data were collated at each site, namely altitude, aspect and underlying geology, to identify possible correlation's with rock type and slope characteristics. The nature of the land use was also recorded, though in some cases the use to which land is put in our time has changed since the kilns were built. In addition, a comprehensive architectural record was compiled, and measurements taken, to try and establish patterns of style and size across the area. A record was made of the condition of the kilns with a view to recommending any worthy of preservation and grant aiding. Finally, a photographic record was made.

Findings

Geology: Of the 61 sites that were precisely located, 88 per cent occur on a limestone surface, the remainder being either on a Carboniferous sandstone or earlier Silurian base. There might seem a paradox here: it clearly makes sense to have a lime burning operation on limestone, but was the burnt lime being used to neutralise the acidity of the soils within the vicinity of the kilns, or elsewhere? If the latter, then burnt limestone -being less bulky than unburnt stone -could be transported more easily and thus more cheaply to where it was required. But, in many cases where the kilns are clearly too small to have operated on a selling basis, the burnt stone was indeed used to sweeten the soils of local limestone pastures. A conspiracy of low average temperatures and high precipitation levels ensures that even limestone soils are acidic in nature.

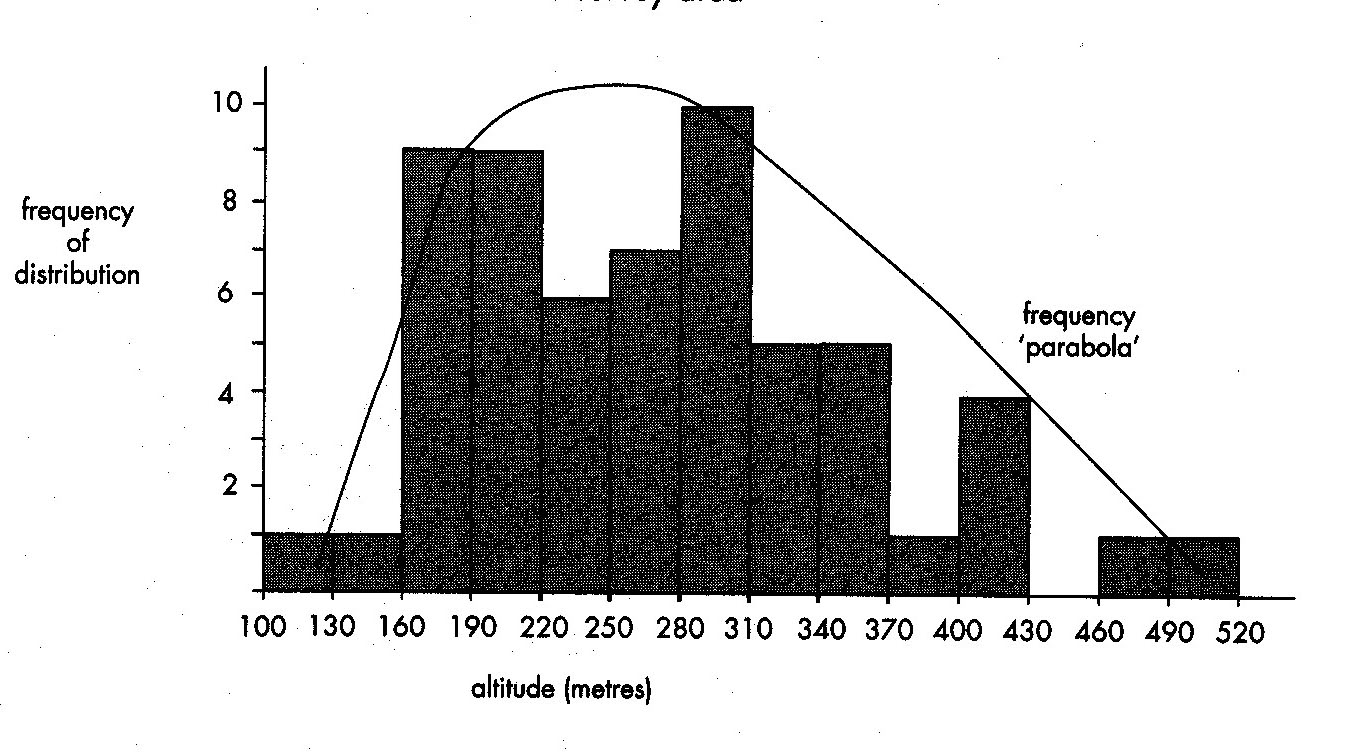

Altitude: Within the study area limestone forms the surface bedrock to an altitude of 450 metres or so. It could arguably be assumed that the most acidic soils - and thus the production of lime for agricultural purposes - would be found in the higher and less sheltered areas, the areas of greatest need. Conversely, one might expect fewer kilns in the lower areas. However, the higher and more exposed parts could be considered to be so marginal even for sheep that the land was not worth treating at all. Taking all this into account, one might thus expect a graph plotting altitude of kilns to form a natural distribution; few low down and high up, with a concentration at middle altitudes.

This indeed is the case; 74 per cent of the surveyed kilns lie between 150 and 300 metres, with 4 per cent lower down and 22 per cent higher up.

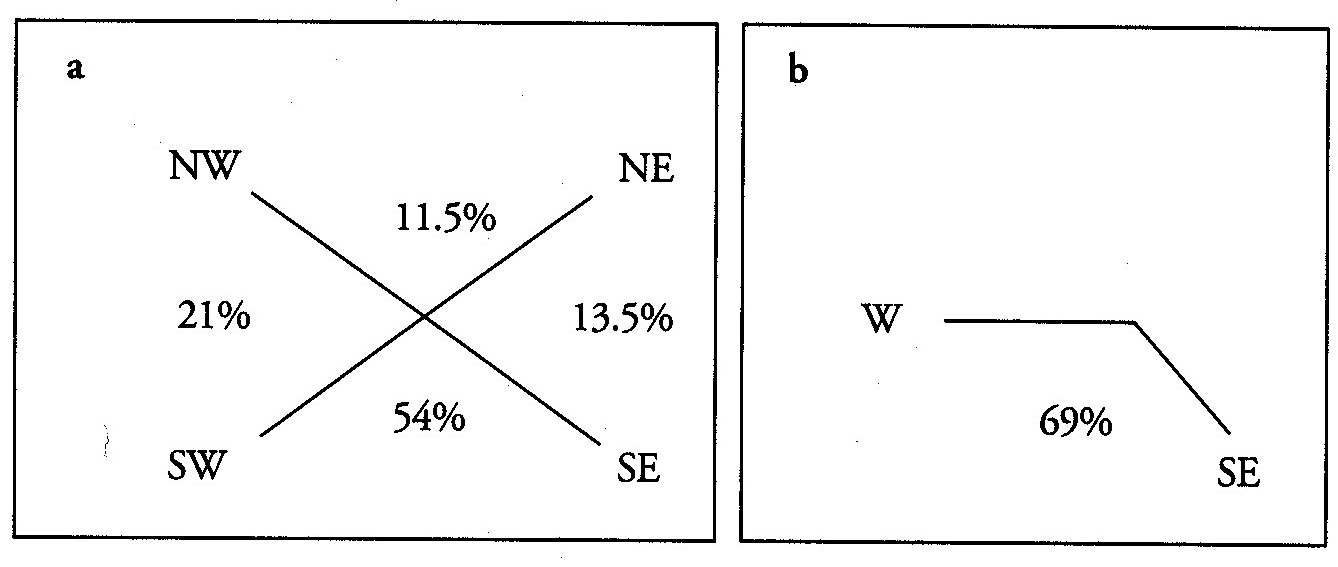

Aspect: The correlations with altitude and geology are relatively easy to explain away, but can the same be said for aspect? Fig. 3a shows that almost half of the kilns faced south.

Fig. 3b shows that 69 per cent faced between west and south-east. Those that faced the north quadrant were, with few exceptions, either at low altitudes or sited to exploit a local topographic advantage. So, what was the significance of aspect? Kilns of any type need an oxygen input to maintain a constant fuel burn. In more modern kilns oxygen induction can be arranged artificially, so to speak, but field kilns needed a natural inflow of air. I can only assume, therefore, that field kilns ideally faced between west and south-east to take full advantage of the prevailing south-west winds.

Land Use: It is well known that many kilns were erected as one part of the reclaiming and allocating of open pastures in the early nineteenth century - part of the Enclosure Movement - so it should come as no surprise that 68 per cent of the sites in the study area are on such enclosed land. Only one kiln in the survey is on open moorland. Of the remaining 13 sites that are found either within woodland plantations or in, or adjacent to, quarries all but three were kilns operated on a commercial basis. These three, all in Clapham township, are difficult to explain away. They are shown as being within plantations that pre-date the building of the kilns and there is no evidence on the ground of coppicing within these woods, so it would be too conjectural to suggest that their prime locational factor was the presence of fuelwood.

Size: According to Searle in his technical tome, field kilns were typically six metres deep, round, and 1.8 metres in diameter at the top. White, in his recent book, suggests that Dales kilns were typically 3.5 metres deep. It proved very difficult in the survey under review to confirm either of these because so many of the kilns have gone. Only 15 kilns in the entire survey still stand more or less undamaged, with a further eight being ruinous. The rest have been robbed out, defunct kilns having been a ready source of building stone. Eleven have disappeared without trace.

Any comment on size is, therefore, partial and must be based on the vertical measurement of the front face of the kilns. It is impossible to measure inside the bowls because of collapse or infill, but the outer measurement will not differ significantly from the inner. Of the 12 field kilns for which measurements were obtainable, only three stand at or almost at six metres, and only two at around 3.5 metres, the full range of depths ranging from 2.6 to 7.45 metres.

Capacity: It is also possible to compute the volume of a kiln using diameter and height measurements. This has been done for three field kilns and two commercially operated kilns. Capacities for the field kilns ranged from 18 to 22 cubic metres; for the two other kilns 34 and 40 cubic metres respectively. Given that one tonne of lime was applied per hectare on slightly acidic pasture and up to four tonnes on severely sour land (one tonne being two cubic metres as a rough approximation), this indicates that a single burn of a lime kiln was sufficient for treating about ten hectares of slightly acidic or 2.5 hectares of highly acidic pasture.

Dating: Precise dating of field kilns is an exercise fraught with difficulty. For this survey, as already mentioned, two sets of maps were consulted and compared. Theoretically it should be a relatively easy task to cross-check and date individual kilns. For example, one kiln in Stainforth township did not appear on the Tithe Plan but is shown on the Ordnance Survey map, so can we assume this kiln was built between 1841 and 1851? Were it that simple! Another kiln in the same township is shown on the 1841 plan but not on the 1851 map. Had it disappeared in the meantime, or is it due to a map omission?

Any attempt at ascribing dates must necessarily be tentative, and it has not even been attempted here, though it has been described in the full report.

Recommendations

Bearing in mind that so many field and commercial kilns have gone, it is perhaps all the more important to preserve, or conserve, those that remain intact. In the survey there are some well preserved kilns far from any right of way. These have survived the depredations of the past, and will probably remain into the future as landscape features because the farmers value them for what they are. Should public money be spent on consolidating such kilns to which the public has no right of access? Some may well argue along these lines, quite justifiably. Others might maintain that kilns in good condition should have money spent on them, regardless of where they are found. There are some kilns within the survey area which are adjacent to, or visible from, rights of way so a stronger case for conservation could perhaps be made for these.

Recommendations are being made to the National Park as a result of this survey to preserve 13 kilns (Fig.4). It is, of course, for the Park officials to make a decision.

Fig. 4 Kilns possibly worthy of preservation

|

Township |

No. of kilns |

No. on |

|

or near a |

||

|

right of way |

||

|

Stainforth |

3 |

2 |

|

Langcliffe |

2 |

1 |

|

Settle |

2 |

1 |

|

Giggleswick |

3 |

2 |

|

Lawkland |

1 |

1 |

|

Austwick |

2 |

0 |

|

Clapham |

0 |

- |

In conclusion, all I feel able to do is to reiterate the final remarks of Ingram Cleasby who expressed the view that "surviving kilns should surely be preserved as a memorial to a remarkable achievement". Indeed they should.

References

Cleasby, I. 1995. "Limekilns in Sedbergh, Garsdale and Dent". Current Archaeology, 145.

Searle, A.B. 1935. Limestone & its products. London: Ernest Benn.

White, R 1994. "Lime kilns". Journal of the North Craven Heritage Trust.

White, R 1997. The Yorkshire Dales. London: Batsford/English Heritage.

Fig. 2 The geographical distribution of the sites across the survey area

Histogram to show altitudinal distribution

of kilns in the survey area

Fig. 3 Aspects of 46 lime kiln sites