| JOURNAL 1999 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

Over the past three years or so Northern Archaeological Associates (NAA) have provided archaeological consultancy services to Yorkshire Water to assist them in protecting archaeological sites and monuments. Because developments such as new pipelines are often several kilometres long and run through both urban and rural landscapes, there is a strong possibility that they will run close to, or possibly bisect, known or unknown archaeological features. For instance, a document search and field reconnaissance within the study area of the recently constructed Settle to Ingleton pipeline identified 70 sites of potential archaeological significance in close proximity to the 55 km long pipeline route.

In the not-too-distant past, in the days of 'rescue archaeology', archaeological features, other than perhaps scheduled sites and monuments of national importance, would almost certainly have been destroyed by such schemes, with little or no funding available to record the sites prior to their destruction. Over the past ten years a remarkable sea change has occurred within British archaeology; procedures have matured to the extent that archaeological advice to planners and developers is sanctioned by official guidelines published by the Department of the Environment. In tandem with this has been the growth of developer funding whereby the cost of archaeological investigation is usually paid for by the developer of a site rather than from the public purse, as was previously the case.

Archaeological input into pipeline schemes can best be described as a staged process of investigation, starting at a documentary search through to survey and, if necessary, trial trenching and excavation. Early on in the route planning process a desk-based assessment can be undertaken, using readily available documents, maps, photographs, plans, and sites and monuments database entries to gauge the distribution and nature of known sites in the area of the route. From an archaeological point of view the optimum route option is the one which has no impact on any sites of archaeological significance. This is because, in planning terms, there is a presumption in favour of preserving in-situ a monument and its setting. An archaeological success story therefore is one where absolutely no archaeology is destroyed by the pipeline works. Whilst this may make for boring articles and lectures it does drive home the fact that archaeology is a finite resource and that the complete avoidance of a site is the best method of protection.

In reality there are a number of technical and practical reasons why pipeline routes sometimes cannot be amended to avoid an archaeological feature. Apart from engineering, land ownership or ecological considerations a route amendment may be considered unfeasible because of the nature of the archaeological site or feature itself. For instance, long linear dikes or boundary features which run at right angles to the direction of the pipeline corridor present an almost insurmountable obstacle. In such instances it may be agreed that the section of the monument that will be affected by the corridor represents but a small fraction of its actual length and recording and excavation of the feature would be regarded as an acceptable alternative to its total conservation. This situation is perhaps a second best option and leads to a situation of 'preservation by record' or less euphemistically, excavating part or all of the site followed by publication of the results.

In the circumstance described above, where it can be established, prior to the start of the construction of the pipeline, that there will be an impact on an archaeological feature, a strategy can be devised to minimise the impact of the pipeline works on the site. Such a strategy will ensure that physical destruction of the archaeology is restricted to the absolute minimum and an appropriate record is obtained of the part of the site affected by the pipeline.

This is all well and good when the location, extent and nature of a site is known prior to the start of the pipeline construction- Not so straightforward is the situation whereby a hitherto unknown site comes to light as a result of the pipeline works, usually at the preliminary stage of topsoil stripping within the fenced corridor of the pipeline route. One such site was discovered during the construction of a new pipeline in Wensleydale, close to the village of Thornton Steward. The pipeline route ran from Thornton Steward Water Treatment Plant (SE 184 887) to a covered reservoir at Sowden Beck (SE 145 848) above the village of East Witton. A preliminary assessment identified five sites of archaeological significance along the route of the 8 km long pipeline. Included among the report's recommendations was that a watching brief should apply where the corridor ran between the St Oswald's church at Thornton Steward and the site of a possible small medieval Chapel situated close to Danby Hall in a field called 'Chapel Garth'.

An archaeologist was monitoring topsoil stripping where the pipeline corridor ran c.200m to the west of the church when she observed fragments of poorly-preserved bone lying on the freshly stripped surface. The machining was suspended and further hand cleaning confirmed that that the bone fragments were human. After immediate consultations between archaeologists and representatives of the parish council, ecclesiastical authorities, the landowner and Yorkshire Water it was decided that excavations should proceed to gather further evidence on the nature of the site, and in particular determine the extent and date, if possible, of any surviving burials. A geophysical survey was also commissioned to establish if any features were present adjacent to the corridor. Meanwhile, all pipeline construction operations which could have an impact on the site were suspended for the duration of the excavations.

After three weeks of excavation the nature of the site could be ascertained: seventeen burials were present within the stripped corridor, many in shallow graves, orientated east to west. All but one of the bodies was orientated so that the head was at the western end of the grave, with the exception laid with his head to the east. Several burials had been disturbed by the insertion of later burials and in some instances the bones of the primary burial had been carefully arranged around the second interment. No grave goods were present and only a few corroded nails were located.

The cemetery was located midway between the church of St Oswald and the site of a possible early medieval chapel but was sufficiently distant from them both not to be associated with either monument. Nonetheless the evidence of body orientation and the absence of accompanying grave goods suggested that the cemetery was Christian rather than pagan. This was confirmed by radiocarbon dates from three burials which covered a date range of AD 660-1020. Curiously, a single cremation was recorded and this was dated to the Bronze Age, some 2500 years earlier than the inhumations. Immediately adjacent to the corridor the geophysical survey plotted sub-circular and rectilinear anomalies that are almost certainly of archaeological significance. Whether they are related to the prehistoric cremation or the Christian inhumation cemetery, unfortunately remains unknown.

The bones were examined by a palaeopathologist and then returned to the village. After a simple but moving service, conducted partly in Latin, the remains were interred in the graveyard of St Oswald's Church where a commemorative plaque has been erected to mark their location.

The Thornton Steward cemetery investigation is important for a number of reasons. On a general level it puts to rest the shibboleth that all development is a 'bad thing' as far as archaeology is concerned. A hitherto unknown site of no small significance has been placed on archaeological map for present-day and future scholars to study. A report on the results of the excavation has been compiled and lodged in a public repository at the Heritage Unit of North Yorkshire County Council.

More specifically, at Thornton Steward it was demonstrated that the burials were close to the surface and that an unknown number of burials had been destroyed, probably by ploughing and animal activity. In all probability the remaining burials would have suffered a similar fate in a relatively short period of time. In the event a completely unknown site was investigated in a professional manner, with due respect being paid to the wishes of the local community.

And finally...it has been stated by some sections of the archaeological community, with justification, that whilst the current planning guidelines allow for archaeological investigation of a threatened site, this can be to the detriment of an investigation into the wider context of the site. The Thornton Steward pipeline investigation demonstrates that this need not always be the case. The geophysical survey undertaken adjacent to the corridor, and therefore outside the area of development, goes beyond the remit of what would normally be required by developer funding. The survey could be a 'springboard' for future research into what is undoubtedly a site of great archaeological significances

Philip Abramson is a professional archaeologist working for NNA of Barnard Castle. The firm has undertaken many projects on behalf of Yorkshire Water.

J1999p1_9_files/tmpBF8-2.jpg

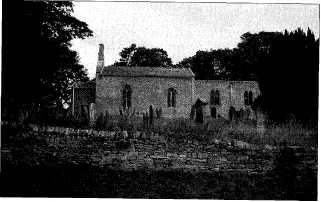

St Oswald's Church

J1999p1_9_files/tmpBF8-3.jpg

Excavating on the Thornton Steward pipeline - a double burial