| JOURNAL 2008 |

| North Craven Heritage Trust |

Introduction

Although the droving of Scottish animals became an important feature of Craven’s economy in the middle of the 18th century, the only surviving contemporary account appears to have been that of Malham school teacher, Thomas Hurtley. In 1786 Hurtley gave a report of Skipton drover John Birtwhistle purchasing cattle in the Hebrides in 1745, and organising fairs on Malham’s Great Close, where 20,000 cattle were sold each year. In recent years historians have become sceptical of Hurtley’s account, suggesting that it was more likely that John Birtwhistle bought his cattle in Crieff and Falkirk, where the Duke of Cumberland’s troops are known to have sold cattle confiscated from the clans to drovers at bargain prices.

This article describes the results of new researches in a number of English and Scottish archives into the surviving records of John Birtwhistle and three of his sons who were also drovers. Not only do the records suggest that Hurtley’s account was substantially correct, but that, for three quarters of a century the Birtwhistles appear to have run the largest cattle business in Britain. Initially they handled Highland cattle but, from the 1780s, started to concentrate on Irish cattle coming through Galloway, and involved themselves in textile manufacture. Financial success enabled the Birtwhistles to purchase extensive estates in Galloway, Craven and Lincolnshire, cattle being taken to market as far south as Suffolk. The largest single estate held by the Birtwhistles was of 872 acres, on the hilltops above Long Preston, an estate which handled cattle in transit between the Birtwhistles’coastal holdings in Galloway and Lincolnshire. Towards the end of the 18th century Cheviots were successfully introduced into the Highlands and records show John Birtwhistle’s sons leasing a substantial sheep raising estate in Ross-shire, to the north of Loch Maree.

Although there are frequent references in the archives to a property portfolio built up in Craven by John Birtwhistle and his sons, none of the records from their lifetimes are specific about the exact location and size of these holdings. This information comes to us from a celebrated inheritance dispute between John Birtwhistle’s daughter, Agnes, and one of his grandsons, also John Birtwhistle, which lasted from 1823 to 1830 and was finally settled in the House of Lords. The records of this case are important to our understanding of the different of roles of the various Birtwhistle holdings in Galloway, Craven and Lincolnshire. Judgement in Birtwhistle vs Vardill was internationally important, and has been built into the constitution of several countries, including that of the United States. A surprising finding of the research has been that Agnes Birtwhistle’s husband, Dr John Vardill, was an important spy for the British Government, spying on the French and Americans for George III. Dr Vardill’s residence with the Birtwhistles in Galloway would appear to have been related to the British Government’s concerns about French and American interference in Irish politics and it is even possible that there was a “political” dimension behind the settlement of the extended Birtwhistle/Vardill family in Scotland.

The Craven agricultural landscape at the beginning of the 18th century

Before the growth of the droving trade in Scottish animals in the middle of the 18th century, open townfields filled most of Craven’s valley bottoms, where oats were grown for human consumption, together with hay to over-winter cattle which lived on the hilltop pastures in summer. Such field systems were still in place when the West Riding Deeds Registry opened at Wakefield in 1704 (now WYAS/W), and early Wakefield deeds give us the names of many open townfields and closes. Most of the early 18th century field names survived to the Tithe surveys of the 19th century, enabling us to reconstruct maps of the main field systems of many Craven townships as they were before the coming of the droving trade. Such reconstructions of township field systems have previously been published for Settle, (Stephens 2001) and Giggleswick, (Stephens &Moorhouse 2005), and that for Long Preston, where the Birtwhistles would later centre their Craven cattle business, is shown in Figure2.

Some Craven fields which show signs of early ploughing had already been enclosed before the 18th century and these appear to have been held by freeholders and others who did not need to seek the lord of the manor’s permission to change their farming methods. It is likely that these fields were enclosed around the middle of the 17th century, when pastoral farming started to become more profitable than arable farming, and two examples of such enclosure for Long Preston are shown in Figure 2, viz

- the Riddings, identified as an ancient freehold property in a survey of 1499 (CH BAS/47/1)

- a block of land identified in a survey of 1579 (YAS DD121/2) as former Bolton Priory lands. The location of this former monastic land to the west of the village may be identified through field names which appear in early 18th century deeds at Wakefield.

John Birtwhistle (1714- 1787)

John Birtwhistle was born in Skipton into a modest yeoman farming family. His father, Thomas, died intestate in 1735 (Stavert 1895), but the probate records of his grandfather (William Birtwhistle’s probate, 1715, BI/Y) tell us that the family home had two ground floor rooms, a parlour doubling as a bedroom and two chambers above, one with a bed and the other containing household goods. For a family which would later dominate the northern cattle business for three quarters of a century, there was a minimum involvement in husbandry in 1715, only two cows and two stirks being listed. The Skipton Parish Registers describe Thomas Birtwhistle variously as a yeoman and a “badger”( a travelling salesman), the latter being an occupation which may have influenced John to choose a life which involved extensive travelling. John’s first appearance in the archives is as signatory to the sale of an inn in Long Preston in 1740 (WYAS/W MM712 1009), the deed describing him as a Skipton yeoman. The inn may be identified in later Wakefield deeds as the Maypole Inn, and would be in the ownership of his grandchildren a century later.Thomas Hurtley’s account describes John Birtwhistle ”travelling the Hebrides and Scottish Isle and Counties of the north of Scotland, and that at a hazardous time in 1745… every herd enticed from the soil and ushered into this fragrant pasture (i.e. Malham), by the Pipes of an Highland Orpheus” (Hurtley 1786) and tells us that Birthwistle held fairs on Malham’s Great Close with 5000 cattle being on the close at any one time and 20,000 over a summer. There is need to be sceptical about these claims, both because there is no contemporary corroboration and because the account was apparently written four decades after the events described. It has been suggested by others (Harland 1998) that Birtwhistle may have purchased his cattle in Crieff or Falkirk in 1745 rather than the Hebrides, for the Duke of Cumberland’s troops are known to have sold confiscated cattle to drovers at knock-down prices.

An important piece of evidence which puts a new complexion on Hurtley’s account comes from an article in the Dalesman, in which Professor Hodgson described how Thomas Hurtley’s book was produced in 1786 (Hodgson 1984). The copy of Thomas Hurtley’s book acquired by Professor Hodgson included a handwritten manuscript by a contemporary of Hurtley which explained that Thomas Lister had summoned Hurtley to Tarn House, his country mansion at Malham Tarn, and had taken over the editorial control, production and distribution of the book. Lister had “procured him more subscribers and superintended the publication…had the plates drawn and engraved at his own expense……he (Hurtley) never saw his book again”. The importance of this story is that it tells us that the editor of Hurtley’s book was John Birtwhistle’s landlord, someone who knew John Birtwhistle and his business activities extremely well. John Birtwhistle had hired the Great Close from the Listers in 1745, and a record of 1786 in the archives at the Yorkshire Archaeological Society in Leeds (YAS MD 335/1/4/5/3) shows him still hiring the Great Close in the year of the publication of the book, when there were considerable business dealings between the two men (Birtwhistle supplying cattle to Lister at Gisburn Park and Lister providing Birtwhistle with hay and oats). It is normal for a landlord to render an account to his tenant, but it was Birtwhistle who rendered the account to Lister which is now at the YAS. Birtwhistle had lent Lister a considerable sum of money, and the account was of the residual debt after deductions of the rent for the Great Close for the years 1780-85. There is a comment in the account that Lister had failed to fulfil a promise to provide “a meadow enclosed and walled in the Great Close which never was yet done”. No one will have known better than Lister how many animals Birtwhistle had on the Great Close, and Lister’s involvement in the publication of the book gives credibility to the estimate of 20,000 animals on the Great Close in a year, which would have given John Birtwhistle control of some 20% of the cattle coming into England from Scotland.

If there were 5000 animals on the Great Close at any one time, as Hurtley claimed, this would have required upwards of 50 drovers to bring them there and many no doubt would have frequented the drovers inn whose remains may still be seen on the Great Close at SD 905 666. According to local accounts, there were nightly festivities to primitive music at the inn and Margaret Hurtley, Thomas Hurtley’s grand-daughter, was a clever step-dancer who danced in public when she was approaching 80 ( private communication Richard Harland).

The 732 acre Great Close at Malham appears to have been an important factor in John Birtwhistle’s early success in the droving business, providing him with a considerable advantage over his competitors such as Scottish drover Alexander Gray from Rosshire, who wrote when arriving in Skipton in 1746 … “the county is full of their own cattle at such a price as was never known. I have seen local steers sold for 35s to £3… the chief reason is scarcity of hay… above a shilling a stone in spring… cattle that are full fat for present use begin to sell well… what helps their sale is a little demand from Holland… there is plenty of moors and cheap wintering in Craven for cattle such as mine tho not for their own breed. But the dealers are all served from Falkirk and Crieff”(Harland 1998). The shortage of hay for Gray and other drovers was the result of Craven’s agriculture being largely medieval in the middle of the 18th century, only sufficient hay being produced to over-winter the local Craven cattle.

John Birtwhistle married Janet Shearer in Falkirk in 1741, suggesting that John was already actively dealing in Scottish cattle before the Jacobite Rebellion. Falkirk was clearly an important centre for the Birtwhistles, and there is a record of John Birtwhistle buying property there in 1756 (NAS RS 59/22 no 41 1790). Thomas Pennant described Falkirk as “ a large ill-built town supported by two great fairs for black cattle from the Highlands, it being computed that 24,000 head are annually sold there” (Pennant 1769). The British Linen Bank advanced John Birtwhistle £2000 to buy cattle in Falkirk in 1767 (Bonsor 1970 p80) and the Birtwhistles maintained property in the town until 1800, when his son sold a house and yard on the south side of Falkirk High Street to Alexander Shearer, physician (RS 59 Vol 36 No 197), presumably a relative of Janet Shearer.

Although there is no record of where John Birtwhistle purchased his animals in 1745, we do known that he travelled to the Hebrides to buy cattle in 1763, for there was a court action brought against John Birtwhistle by George Gillenders, the factor of the Isle of Harris, in 1764. According to Gillenders, John Birtwhistle had purchased the island’s black cattle in the previous year, but the bond he had given in payment had failed….. “John Birtwhistle in the month of June last came to the north of Scotland to purchase black cattle and in the course of his dealing came to the Island of Harris and applied for credit to purchase the cattle of the island that is annually sold for paying the proprietors rents…. In consequence of this credit Mr Birtwhistle made a tour of the island and purchased cattle to the value of £500” (NAS GD427/242/1). John Birtwhistle was again in a dispute over the purchase of Hebridean cattle in 1767, when the factor for Mackensie or Seaforth (Lewis) stated in court “of late years it had been usual for dealers in black cattle in our neighbouring country to come or send to the remotest part of Scotland to purchase cattle” (Haldane 1997, p179).

No deed has yet been found to tell us when Dundeuch was purchased, but the Birtwhistles would appear to have come into the ownership of this 600 acre moorland estate near New Galloway during John’s lifetime (Birtwhistle 1989). A later newspaper advertisement for the sale of Dundeuch tells us that it was suitable for Highland black cattle and sheep (DS 11April 1810), and it is likely that the black cattle coming from the Highlands to John Birtwhistle’s fairs on the Malham Great Close came through Falkirk and Dundeuch.

By the 1760s many of Craven’s pastures had been enclosed to serve the droving trade, and the dairying industry which came with the droving trade, and Craven farmers would have been able travel to Scotland to buy cattle for their new enclosures without using John Birtwhistle as an intermediary. There is evidence of John Birtwhistle changing the nature of his business to keep ahead of the competition; no longer simply buying Scottish cattle to auction in Craven, but fattening them and selling them further south. He was now a wealthy man, described in records as a gentleman rather than a yeoman or a drover. His wealth enabled him to make substantial purchases of property, including

- in 1762, a substantial freehold property at the south end of Skipton High Street, which included a malt kiln (Rowley notebook 1 p167), on a site where Woolworths and Supadrug now stand

- in 1764, extensive lands in Craven (WYAS/W BA43 63). Much of this property was still in the hands of the Birtwhistle family 60 years later

- in 1769, a rectory and lands at Skirbeck on the Lincolnshire coast, his son Thomas being installed as rector (webref2). His son in law, Dr John Vardill, would later hold the adjacent rectory of Fishtoft, and then both rectories following the death of Thomas Birtwhistle.

An advertisement of 9th March 1782 in the Norfolk Chronicle shows John Birtwhistle’s sons, William and Alexander, taking cattle as far as Hoxne in Suffolk …“To all Gentlemen Graziers. This is to give Notice, that on the 14th and 15th of this Instant, March, will arrive at Hoxne, in Suffolk, a large drove of very strong fresh Galway Scots, belonging to Messrs William and Alexander Birtwhistle, and remain there till sold”(webref3). No record has yet come to light to prove that the Birtwhistles took any cattle all the way to London, but this may have been the case for John Birtwhistle’s account with Thomas Lister of 1786 at the YAS makes mention of a bank accounts in both Leeds and London.

The identification of William and Alexander as the owners of the cattle offered in the Norfolk Chronicle advertisement of 1782 suggests that John Birtwhistle had handed his droving business to his two sons, and this is confirmed by a Wakefield deed of 1782 (WYAS/W CK320 457), which records that the property was in Falkirk, Craven and Lincolnshire.

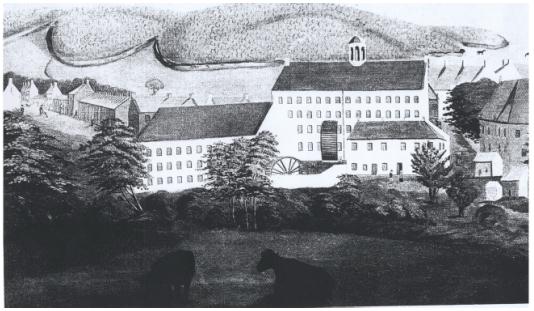

Much of the Industrial Revolution at the end of the 18th century was financed by profits from the earlier Agricultural Revolution, and it is not surprising to find John Birtwhistle’s attention turning to textile manufacture. He was initially unsuccessful when he approached the Earl of Selkirk for permission to build a cotton mill in Kirkcudbright, but James Murray, the landowner at Gatehouse of Fleet, was more amenable and, in1785, an agreement was reached for John Birtwhistle to build a cotton mill in Gatehouse (NAS GD10/1266). The Gatehouse mill was not driven by the adjacent river Fleet, but by water brought four miles from Loch Whinyeon, the agreement stipulating that Murray would bear the cost of building a water conduit from Loch Whinyeon, provided that Birtwhistle refunded this expenditure if the cotton mill was not set to work by Whitsun 1787. The engineering was ingenious, a tunnel bored through the mountain to take the water from Loch Whinyeon westwards, and the spoil from the tunnel being placed at the east end of the loch to raise its level. The main features of the water extraction at Loch Whinyeon and the tunnel through the mountain may still be seen, together with the decayed and overgrown water conduit which follows the contour across the hillside from Loch Whinyeon to Gatehouse. An attraction of Gatehouse as a site for a cotton mill may have been the amount of power which could be extracted from the water brought from Loch Whinyeon. Many early water driven textile mills in the Pennines were limited by their water sources to an output of 10 horsepower while the Gatehouse waterwheels were capable of producing 55 horsepower.

A substantial memorial, high in the aisle of the Parish Church in Skipton, was only erected half a century after John Birtwhistle’s death. As we shall see later, the memorial was less a celebration of John’s life than of the outcome of a protracted and celebrated inheritance dispute between one his grandsons and his daughter.

The second generation; William Birtwhistle (1744-1819), Alexander Birtwhistle (1750-1810) and Robert Birtwhistle (1758-1815)

Despite the Wakefield deed of 1782 which recorded the droving business being handed to William and Alexander, John Birtwhistle’s will (BI/Y) shows that he had decided by 1787 to leave the cattle business to three sons, William, Alexander and Robert, as tenants in common. The cotton mills in Gatehouse were left to William, Alexander, Charles and Richard, also as tenants in common, a form of holding which contributed to much of the business remaining in family hands long after the deaths of the sons, and generated later archival records which have greatly helped the identification of the family property.

The Norfolk Chronicle advertisement which described the cattle on offer in Hoxne in 1782 as Galway Scots was the first indication that the Birtwhistles were handling Irish cattle. Although formerly banned from Britain, an Act of Parliament of 1776 allowed Irish cattle into the mainland and, by 1780, around 10,000 animals a year were being brought from Ireland in flat bottomed boats to Port Patrick and Port Logan (Bonsor 1970 p75). It was probably to capitalise on this new source of animals that William Birtwhistle purchased Balmae (sometimes Balmay) in 1783, a 731 acre estate on the Solway coast, just to the south of Kirkcudbright (NAS CS107/353 &CS107/298). Balmae comprised several contiguous estates, including Balmae, Howell and Raeberry, and the most detailed account of the property is from a newspaper advertisement when William sold the estate in 1810 (DS 21 July 1810)…….“elegant and commodius finished in a style far superior to any other house in the South of Scotland…a garden of four acres of very rich land surrounded by a substantial wall and stored with a great variety of fruit trees…affords excellent accommodation for sea bathing in the purest waters…two commodius harbours…..proprietor has right of Admiralty”. Sadly, the estate is today an MOD firing range and the mansion no longer survives. Although the brothers would later buy other residences in Galloway, Balmae was for several years the main base for the extended Birtwhistle family in Scotland.

John Birtwhistle was an extremely wealthy man when he died in 1787 and his will shows that he made substantial provision for his children and their future offspring, the cattle business being bequeathed to his drover sons William, Alexander and Robert, who were to pay the other legacies. It therefore looks more than a little suspicious to find Thomas, John, Richard and Charles Birtwhistle all dying between 1789 and 1792, leaving an unencumbered business in the hands of the three drovers brothers. The survivors rationalised the businesses, with William and Robert taking over the management of the cattle business, which was run from Galloway and Craven, while Alexander, who was to be resident in Scotland for the rest of his life, ran the textiles business. Alexander was also a merchant in Kirkcudbright (webref4), and the town’s Provost, and was immortalised by Robbie Burns in two ballads when the poet visited Gatehouse in 1795.

| Election Ballad

”roaring Birtwhistle Wha’ luckily roars in the right”

| Laddies by the Banks o’Nith

”To end the wark here’s Whistlebirck Lang may his whistle blaw, Jamie” |

Alexander bought Barharrow, a 464 acre farm near Gatehouse, and then built a substantial property in the High Street, Gatehouse (now the Bank of Fleet Hotel), while Robert appears to have owned no property in his own right, living in properties owned by his brothers. William was the leading proponent of the Parliamentary Enclosure of Long Preston in 1799, and detailed knowledge of the full extent of the Birtwhistle property in Long Preston comes from the family litigation which we shall discuss later.

The selling of the Birtwhistle property in Falkirk in 1800 (NAS RS 59 Vol 36 no 197) probably indicates that the brothers were no longer handling Highland black cattle at the end of the 18th century, but concentrating their cattle business on Irish animals coming through Galloway. It is possible that the cattle seen by government agricultural commissioners in Settle in 1793 were Birtwhistle cattle, for they reported, with some bafflement, seeing cattle which were “long horned and seem in shape, skin and other circumstances to be nearly the same as the Irish cattle” (Brown 1799).

The Highland Clearances would appear to have offered the Birtwhistles new opportunities in sheep farming and Alexander’s probate inventory of 1810 tells us that they had a sheep farm in the Highlands (private communication Richard Harland). It is possible to identify the location of this store farm at Bruachaig in Ross-shire (to the north of Loch Maree) from later records, because the executors continued to run the farm after the death of the three brothers. The executors paid a manager £100pa to manage the estate from Bruachaig and a court action suggests that the manager had diverted Birtwhistle animals to his own use. The court records show that the extensive estate managed from Bruachaig included holdings at Letterewe, Beinn-a-chaisgan, Strathnashla, Sleog and Botag (NAS CS271/54364 &CS271/5045).

When Alexander died in 1810 the children of the three brothers were all minors. Barharrow and Dundeuch were offered to tenants (DS 11April 1810), but Balmae was sold to the Earl of Selkirk for £20,000 (NA prob 11/1618). The offer particulars for Barharrow and Balmae tell us that considerable attention had been paid to improving the soil structure on these two estates during the tenure of the Birtwhistles, by the application of lime, marl, shells, dung and soap-waste but the same attention does not appear to have been paid to Dundeuch, where the residence was said to be in need of replacement. An advertisement of 1825 offering mature birch for sale on the estate suggests that Dundeuch may have been left unfarmed after 1810. Speed’s map of 1799 shows a property at Dundeuch in the ownership of Birtwhistle Esq but all that now remains is a pile of rubble.

William, the last of the brothers to die, ran the cattle business from Skipton and, on his death in 1819 (NA prob 11/1618), the Leeds Mercury advised its readers that the Birtwhistles had been the biggest cattle dealers in the country…. “William Birtwhistle Esq of Skipton, brother of the late Robert and Alexander Birtwhistle. By their deaths the ancient Birtwhistles, the greatest dealers and graziers in the Kingdom are all extinct”. It was rare for a cattle droving business to be successfully handed down the generations, and there is no reason to doubt the accuracy of the Leeds Mercury’s assessment that the Birtwhistles’ cattle business as being the biggest such business in the country. Despite being resident in Skipton after 1810, William would appear to have controlled much of the cattle trade in Galloway until his death for, when taken to court for non-payment of rent shortly after William’s death, the tenant of Barharrow claimed that he, and many other farmers in Galloway, had been bankrupt by the failure of the Birtwhistle cattle business “all the farms in Galloway were in a state of bankruptcy owing to the failure of the principal cattle dealers in the county with whom they were all connected” (NAS CS271/6493).

A fine miniature of William Birtwhistle survives in the ownership of a descendant of Robert Birtwhistle and although the miniature merely describes the subject as “Major Birtwhistle”, it is possible to associate the major with William by virtue of another miniature of 1802 which shows “Major Birtwhistle” of the Craven Legion attending the consecration of the legion’s colours in 1802. The Craven Legion later became the Local Militia, the officers maintaining their former ranks, and a listing of 1809 of the appointments to the Local Militia identifies “Major Birtwhistles as William Birtwhistle Esq (Speight 1892 page 26). Although the figures are too small to be identified, the miniature of 1802 tells us that those who attended the consecration ceremony included Robert Birtwhistle and Hon Thomas Lister ( landlord of Malham’s Great Close). The principal guest at the consecration was W.Pitt, presumably William Pitt the Younger, who had resigned as Prime Minister in 1801 and, like Lord Ribblesdale, was actively recruiting volunteer forces to face a possible invasion by Napoleon.

The third generation

Although William, Alexander and Robert had at least 10 “natural” children by several partners, only Alexander married the mother of two of his children, and that after their birth. William did not specify in his will who should inherit his 1/3rd share of the property in England, and this caused inheritance problems for his potential heirs. Under Scottish law children automatically inherited, regardless of the marital state of the parents, but English law prohibited inheritance to those born out of wedlock unless named in a will.

Agnes Vardill, John Birtwhistle’s only surviving child, took the view that she was the only legal inheritor, applied for and was granted administration of the English estates, and rebuffed Alexander’s son, John, when he came of age and applied to his aunt for a share of the estate in England. John took the matter to the Court of Chancery in 1823 and 1826, claiming that his parents had been secretly married before his birth. Agnes refuted this claim in great detail saying that, at his birth, his mother had been merely his father’s mistress, living first with her parents in Gatehouse, at Balmae and at his farmhouse in secret before living in Alexander’s house in Gatehouse. The court accepted Agnes’s arguments on each occasion until the case was re-opened in the House of Lords (webref5). Their lordships took the view that the consideration was not John Birtwhistle legitimacy, but whether Scottish or English law should prevail and, in a landmark judgement, it decided that the law of the country of birth should prevail. Birtwhistle vs Vardill had legal ramifications far beyond the confines of the Birtwhistle family, its judgement being built into the constitution of a number of countries, including that of the United States.

The relevance of Birtwhistle vs Vardill to our understanding of the Birtwhistle droving business is that the records of the 1823 Court of Chancery case, now in the National Archive at Kew (NA C13/791/18), provide the only complete listing of the Birtwhistle holdings in Craven. Of the 1431 acres in Craven, the largest single holding was an 872 acre estate on the hilltops above Long Preston and Airton (most of Bookilber and Langber pastures in Long Preston and the adjacent Crake Moor and Ormsgill in Airton). Tellingly, 89% of the Craven holdings were pasture, and only 11% meadow, which would only have over-wintered a few hundred animals. An important conclusion which may be drawn from these figures is that the Birtwhistles must have fattened their cattle in Galloway and Lincolnshire and used their Craven estates to handle animals in transit. Until recently the Birtwhistle Bookilber farm on the Long Preston hilltops had an open air kennels and RCAHMS web site also lists a kennel at William Birtwhistle’s former Balmae estate. Since these were two of the main centres of the Birtwhistles’ droving business it is likely that these kennels were built for droving dogs rather than hunting dogs.

John Birtwhistle celebrated his success over the Vardills in the House of Lords by erecting a large memorial in Skipton Parish Church to his grandfather, listing all his grandfather’s descendents down to himself, but omitting any mention of Agnes Vardill or her family. A valuation for a pew in Skipton Parish Church is included in the records of the Chancery case of 1823, and it is likely that this will have been the pew tied to the family freehold property in Skipton High Street and will have been directly below the memorial to John Birtwhistle. The position of the pew, at the front row of the church, tells us that the Birtwhistles were in the highest rank in Skipton society, and the brass memorials in the church to John Birtwhistle’s sons, who served in the armed forces in India and in the Chinese Wars, suggests that John Birtwhistle took his position in Skipton society on acquiring the High Street property.

There is no record of John running any of the businesses, and he may simply have lived the life of a gentleman on unearned income, dividing his time between Skipton, Kirkcudbright (where he was deputy Lieutenant), and France. He returned from France to Gatehouse in haste in 1843, when a bad debt of his wife threatened seizure of his assets and the ensuing court action (NAS CS13/905) is important because it lists John’s assets in Galloway. These comprised Barharrow, 1/3rd of Dundeuch, ½ of the two cotton mills at Gatehouse and a residence in Gatehouse. This confirms that Barharrow had been owned solely by Alexander Birtwhistle and that Dundeuch was held jointly by his father and his uncles- the only confirmation of the contention that Dundeuch was originally in the ownership of John Birtwhistle (senior).

Robert Birtwhistle’s descendents seem to have benefited from the House of Lords action initiated by his cousin. They may have been the “poor relations” referred to in Agnes Vardills will of 1826, for the 1823 Court of Chancery action recorded Robert Birtwhistle’s common law wife, Ann Burton, now a widow, living in Skipton as a tenant of Agnes Vardill and paying her a rent of £7 7s for a cottage. Her son, John Burton Birtwhistle, was the curate at Burnsall in Wharfedale in 1826, a lowly position compared with the rectories held by his uncles, Thomas Birtwhistle and John Vardill. However, a Wakefield deed of 1839 (WYAS/W NF411 388) shows that John Burton Birtwhistle and his two brothers had become the owners of lands in Long Preston, and the Tithe Survey of the same year identifies these lands as the Langber and Bookilber pastures which were formerly held by William, Alexander and Robert Birtwhistle. John Burton Birtwhistle’s ecclesiastical career flourished with his new found wealth, and he progressed from curate of Burnsall to Perpetual Incumbent of Beverley Minster and Canon of York Minster!

Desnes 1923 tells us that several of the Birtwhistle family, including Alexander Birtwhistle, had associations with three properties on the corner of St Mary Street and St Cuthbert St in Kirkcudbright, which included the Commericial Bank of Scotland and the Commercial Hotel, the middle building being originally in the name of Jane Kissock, nee Birtwhistle. Although Jane’s position has been maintained in the family tree of Figure 2 as in Birtwhistle 1989, where she is shown as the daughter of William Birtwhistle, William described her in his will (NA prob 11/1618) as the reputed daughter of his brother, Alexander. According to Desnes, another of these three properties was associated with Colonel Birtwhistle, presumably Alexander’s son, suggesting that the three properties may have been built by Alexander for himself and his children.

William’s will acknowledged John Dixon of the 32nd regiment as his “reputed son” and John Dixon must have been the Ensign Birtwhistle of the 32nd who is recorded in an oil painting of the Battle of Waterloo thrusting a sword into a French officer who was trying to steal the King’s colours ( webref8 ). A letter to Skipton from a Thomas Birtwhistle of Reading in 1977 recorded that he had in his possession a Waterloo medal with “Ensign John Birtwhistle 32 Regiment of Foot” engraved round the edge (Rowley Notebook 2 page 84).

The Vardills

The Vardills are not only of interest to our story because of the court case which revealed the location of the Birtwhistle holdings in Craven, but because of the possibility that Dr John Vardill’s occupation may have had some bearing on the Birtwhistles and Vardills becoming resident on the Solway. Some of our information about Dr Vardill comes from the pen of his daughter, Anna Vardill, a child prodigy who became a prolific writer, poet and contributor to the European Magazine between 1809 and 1822 under the pseudonym V, and moved in the highest literary and social circles in London (Axon 1908), (webref6).

Some of Anna’s writing contains barely concealed biographical details about the Birtwhistles, including references to Balmae and Gatehouse, and stories of an unexpected legacy and the reading of a will. In 1822 she married James Niven of Kirkcudbright, who had represented the Birtwhistles on a number of occasions, including the sale of Balmae in 1810 (DS 21July 1810). Literary critics ascribe Anna’s failure to publish after 1822 to her marriage, but it is equally possible that the Birtwhistle vs Vardill lawsuit may have absorbed her energies, particularly after the death of her mother, Agnes Vardill, when Anna became the defendant.

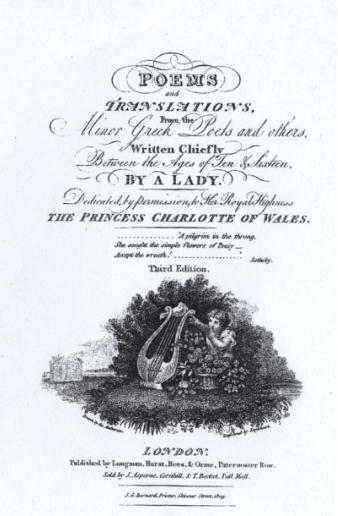

It is only from Anna’s writing that we are aware that the Vardills lived on the Solway, probably William’s residence at Balmae first, and then at Alexander’s residence in High Street Gatehouse. Anna’s publication of 1809 “Poems and translations, from minor Greek poets and others, chiefly written between the ages of 10 and 16, by a lady” (Lady 1809), now in the British Library, was dedicated to the Princess of Wales, and evinced a letter from St James Palace informing her that the Prince of Wales, the future George IV, had enjoyed the work (Axon 1908).

Anna’s poem of 1807 includes the two lines

”Nine summer suns have shone since by thy side

O’er the rich bank of Gentle Fleet I hung”

suggesting that she was living in Gatehouse until 1798 and that the poems were written there. The engraving at the front of her book shows a young girl in undergrowth on what appears to be a riverbank, possibly an allegorical representation of Anna’s early life, with the author on the riverbank and Cally House or Balmae behind.

In her writing Anna merely describes her father as a retired rector, but does not explain how she came to have connections with the royal family - the result of her father being one of the most senior agents in the British Secret Service. Dr John Vardill had an office in Downing Street, reflecting the importance of his work for the state, and provided intelligence which was read by George III. Much is known about John Vardill’s early spying career from American sources (Einstein 1933), (webref7), because he was an American who spied for the British during the War of Independence. Vardill was well connected, being a Professor at Kings College New York by the age of 23, and a correspondent of George Washington (webref10), but his sympathies lay with the Crown. When he visited London in 1774, to make a case for Kings College being awarded the status of a university, he was recruited into the Secret Service by William Eden, Under Secretary of State and Head of the British Secret Service. George III rewarded Vardill with the appointment of Regius Professorship of Divinity at Kings College New York, a post he was never to take up because American Independence precluded him from returning to America.

Vardill decoded secret messages for the British government, providing code names and addresses of American sympathisers in England and, in 1777, organised the stealing of correspondence between Benjamin Franklin’s American Commission in Paris and the French court, the correspondence being diverted to London for George III to read. Some of his enterprises, such as the putting of agents into London brothels, were somewhat unusual for a Regius Professor of Divinity!

It was the custom of the times for spies to have pseudonyms, George Washington being simply “code 711” and, in view of the fact that one of Vardill’s jobs was the identifying of the American code names, it is astonishing that he should choose a pseudonym for himself which we find so easy to decode. No doubt it was vanity about his close connections to royalty which made him choose Coriolanus, the name of a Roman hero who was exiled and took refuge with a foreign king. John Vardill had agents working for him in London and we must assume that this was still the case when he lived on the Solway. Anna tells us that a Monsieur Cramozin of Rouen, tutored her in French in Gatehouse, and this must surely be a code name. In a poem by the medieval French poet Villon, there is mention of a cramozin (crimson) cloak(webref9), which would have been an appropriate, if rather obvious, disguise for an agent working for a Regius Professor of Divinity. It was perhaps Vardill’s laxness in choosing cover names which made it so easy for American historians to research his spying actions against them.

We know less about Dr Vardill’s later spying operations in Ireland, perhaps because they were of little interest to American academics, although Einstein tells us that Vardill was entirely devoted to the service of the British Government in the years 1775-1781, and continued to be paid by the British Treasury until 1807. Vardill’s superior, William Eden, had been deeply involved in Anglo-American politics, including an unsuccessful mission to America in 1778, whose objective was to persuade Americans not to sue for independence and after American Independence he moved from Anglo-American to Anglo- Irish politics, becoming Secretary of State for Ireland in 1780, MP for Dungannon in 1781 and Vice Treasurer of Ireland in 1782. It is therefore almost certain that Vardill’s move to Galloway was also related to Anglo- Irish matters, particularly as there is a record of him being in Ireland in 1785 (Desnes 1923).

There were well founded fears in London that the French and Americans were conspiring to foment insurrection in Ireland, and these fears were heightened when Benjamin Franklin authorised Capt. John Paul Jones to set sail in USS Ranger from Brest in 1778 to harass the British navy. Jones raided the Solway coast, coming ashore at Kirkcudbright, in an attempt to capture the Earl of Selkirk, then captured HMS Drake in Belfast Lough, an action which forced the Admiralty to deploy HMS Thetis to Portpatrick to protect the Irish mail. The Skipton Parish Registers (Stavert 1896 p69) show that John Vardill was a resident of Skipton when he married Agnes Birtwhistle in 1778, and the Birtwhistle droving network must have provided an ideal means of keeping abreast of events in Ireland, London and the continent, both when he was living in Skipton and on the Solway.

Einstein tells us that the Rectory of Fishtoft was given to John Vardill as compensation for being unable to take up the King’s appointment in New York, and it is almost certain that Vardill was working on Anglo- Irish matters under William Eden when he lived in Galloway. The British Secret Service, had a budget of £200,000 in 1780 and William Eden may have helped the Birtwhistles to move to Galloway in 1783, as a cover for John Vardill’s involvement in Anglo-Irish politics. Although there is only mention in Anna Vardill’s writing of living at Gatehouse, it is likely that the Vardills also lived at Balmae, where the extended Birtwhistle family first lived in Scotland. John Vardill’s wife, Agnes, left a legacy to the gardener at Balmae (NAS prob11/1709- Agnes Vardill probate, 1826) and there are frequent mentions in Anna Vardill’s poetry of Balmae, Raeberry and the surrounding countryside.

After Capt. John Paul Jones raided Kirkcubright in 1778, raising fears about Anglo-French interference in Irish politics, it would seems more than a coincidence to find the Birtwhistles buying a property close to Capt Jones’s landing point, only a year after John Vardill’s spymaster, William Eden had become Vice Treasurer of Ireland. Tantalisingly, the anonymous correspondent of the Dumfries Standard (Desnes 1923) knew that John Vardill was in Ireland in 1785, but does not give any information about the visit or the source of his information. It is to be hoped that future researchers in the field of Anglo-Irish politics may provide further information about John Vardill’s “political” activities when he was living in Galloway and whether William Eden had any hand in the Birtwhistles and Vardills settling in Galloway.

A postscript from modern times

Despite corroboration of Thomas Hurtley’s account of John Birtwhistle travelling to the Hebrides to buy animals for auction on Malham’s Great Close, it has always been something of a mystery that John Birtwhistle should travel hundreds of miles through Scotland to purchase cattle in the Hebrides. The mystery would appear to have been resolved by an interview given by Craven farmer Eric Foster to Bill Mitchell in 1987 (Mitchell 1990). Eric had himself travelled to the Hebrides to buy cattle until the 1960’s, and told Bill that Hebridean cattle were much favoured by Craven farmers because of their hardiness. Animals which had withstood harsh Hebridean winters thrived much better in Craven’s difficult climate than animals raised in less arduous conditions on the mainland… “the visitors from the Yorkshire Dales worked on the principle that if they took cattle from hard localities, such as the Hebrides, they were almost certain to have beasts that would “do” back at home. If you were to buy cattle in Oban, you had to watch your job”.

With hindsight, this is a convincing explanation, for much of Craven’s grassland is at an elevation of over a 1000feet, providing an environment which might be too harsh for animals brought up in more favourable climates. Highland cattle have been successfully reintroduced to Malham’ Great Close in recent years because of their ability to crop coarse grass more efficiently than sheep.

Concluding remarks

For two hundred years the story related by Thomas Hurtley of John Birtwhistle, “the Highland Orpheus”, bringing cattle into Craven from the Hebrides in 1745 has seemed little more than romance. However, the story of the Birtwhistles which emerges from the archives is of much greater importance, providing new understandings of the economic and social history of north west England and Scotland of the period.

The massive increase in the number of Scottish animals coming into England in the middle of the 18th century was responsible for an Agricultural Revolution whose physical effects are perhaps best seen in the Craven district of northern west England. For the best part of a millennium, rural north west England had practised mainly subsistence farming based on the growing of oats in open townfields but, by the end of the century, nearly all of these open townfield had been enclosed to serve the Scottish droving trade. Craven’s characteristic drystone walls perhaps provide the best known physical evidence of this change in farming practices. Later in the century north west England was in the vanguard of the Industrial Revolution, partly because the small corn mills which had been made redundant by the Agricultural Revolution could be easily converted to textile manufacturing. The Birtwhistles chose to involve themselves in textile manufacture in Galloway rather than Craven, perhaps because the Galloway water supplies were capable of providing more power than the small Craven streams and rivers.

A problem for historians of this period is that contemporary biographers were little interested in industry and have left us few records. While many of their contemporaries were also involved in droving and textiles, the Birtwhistles appear to have been unique in involving themselves in both activities over a long period of time. These business activities have left a trail in the archives which enable us, to some extent, to compensate for the lack of contemporary biography. Initially we see John Birtwhistle bringing large numbers of Highland black cattle into Craven, where his leasing of Malham’s Great Close gave him a significant commercial advantage over his competitors and allowed him to accumulated capital. This capital enabled him to buy property in Scotland, Craven and Lincolnshire and extend his droving business to that of drover and grazier. With three sons in the business, the Birtwhistles were ideally placed by the 1780s to take advantage of a new source of cattle coming into South West Scotland from Ireland, and their collaboration with James Murray in Gatehouse must have been mutually beneficial to both families. It remains to be seen whether politics played any part in the Birtwhistles and Vardills moving to Galloway at a time when there was concern in London about French and American involvement in Irish politics.

Economists often argue about the degree to which the Agricultural Revolution of the middle of the 18th century financed the later Industrial Revolution, and whether the finance was supplied by the “old” or “new” gentry. John Birtwhistle attained gentry status by the 1760s and records show that he was lending money to his “old” gentry Craven landlord by the 1780s and that the building of the Gatehouse mill was a collaborative venture with his Scottish landowner. James Murray paid for the water supply, while John Birtwhistle incurred the bigger expense of building the mill. In view of the importance of the Birtwhistles to an understanding of the economies of North West England and South West Scotland in the second half of the 18th century and the first half of the 19th century, their records would perhaps justify more systematic research than has been possible during the research for this article.

Acknowledgements

The original stimulus for this research was an article on John Birtwhistle written by Dr Arthur Raistrick in the late 1950s in the Dalesman, but only followed up by the author in recent years. By coincidence, Mr Richard Harland of Grassington, who has also made an extensive study of John Birtwhistle, was similarly stimulated by Dr Raistrick in the 1960s, publishing a paper on John Birtwhistle in 1998 ( listed in the bibliography). When the author and Mr Harland met for the first time in March 2008, they were astonished to find that they had researched many of the same sources, and the author is very grateful for being allowed to use additional sources indicated in the text by “private communication Richard Harland”. The author is also greatly indebted to Mr Bill Mitchell of Giggleswick, formerly editor of the Dalesman, for bringing to his attention to the article by Professor Hodgson in the Dalesman, which is important to any understanding to an understanding of Thomas Hurtley’s book, and to his interview with Eric Foster. The author is also greatly indebted to Dr David Devereux of the Stewartry Museum in Kirkcudbright, to Mr John Pickin of the Stranraer Museum and to Mrs Anna Campbell of the Carsphairn Heritage Centre for their help in identifying sources in South West Scotland, and to Geoff Sharwood-Smith of Edinburgh for information about John Birtwhistle’s marriage to Janet Shearer in 1741 for permission to use the image of William Birtwhistle.

Abbreviations

- BI/Y- Borthwick Institute, York University

- CH- Chatsworth House, Derbyshire

- DS- Dumfries Standard- microfilms held by Castle Douglas Library

- NA- National Archives, Kew

- NAS- National Archives of Scotland, Edinburgh

- WYAS/W- West Yorkshire Archive Service, Wakefield

- YAS- Yorkshire Archaeological Society, Leeds

Bibliography

- Axon, W.E.,1908. Trans of the Royal Society of Literature. Anna Jane Vardill Niven

- Birtwhistle, W.A., 1989. The Birtwhistle family 1200-1850AD. Private publication

- Bonsor, R.G., 1970. The Drovers. MacMillan

- Brown, R. 1799. General View of the Agriculture of the West Riding 1793

- Desnes (pseudonym), 1923. Article in the Dumfries Standard 24/2/1923 (Copy held by the Stewartry Museum, Kirkcudbright

- Einstein,L. 1933. Divided Loyalties. Americans in England during the War of Independence

- Haldane, A.R.B. 1997. The Drovers of Scotland Birlinn Ltd

- Harland, R., 1998. Notes on a talk given to the Malhamdale Local History Group, see webref1 below

- Hodgson,F.1984. Thomas Hurtley and his Guide Book to Malham, The Dalesman Oct 1984

- Hurtley, T., 1786. Natural Curiosities in the Environs of Malham

- Lady ( anon Vardill,A.,), 1809. Poems and translations, from minor Greek poets and others, chiefly written between the ages of 10 and 16; by a lady (Rare Books Reading Room, British Library)

- MacHaffie, F., 2001 Portpatrick to Donaghadee- the original short sea crossing route

- Rowley, R.G., Property owners and tenants of Skipton (Dr Rowley’s manuscript notebooks are in the Skipton Public Library)

- Mitchell. W.R.1990. Dalesfolk Talking. Dalesman

- Pennant, T. 1769 A Tour in Scotland

- Smail, J., 2001. The memorandum book of John Briarley, Cloth Frizzer of Wakefield. YAS. Record Series 155

- Speight, H., 1892. The Craven and North West Yorkshire Highlands

- Stavert,W.J., 1895. The Parish Registers of Skipton in Craven. 1680-1771

- Stavert,W.J., 1896. The Parish Registers of Skipton in Craven. 1745-1812

- Stephens, T. 2001. Settle farmers and traders;New perspectives from the archives on the evolution of Settle, North Yorkshire. Yorkshire History Quarterly Vol7 no 1 pps 31-46

- Stephens, T. & Moorhouse, S. 2005. The Giggleswick Lodges of 1499. YAS Medieval Yorkshire. No 34 pps 2-14

Web references

- webref1: http://www.kirkbymalham.info/KMI/malhammoor/greatclose2.html

- webref2: http://eagle.cch.kcl.ac.uk:8080/cce/persons/DisplayPerson.jsp?PersonID=42875

- webref3: http://www.foxearth.org.uk/1782NorfolkChronicle.html

- webref4: http://www.old-kirkcudbright.net/genealogy/stent/1790stent.asp

- webref5: http://www.british-history.ac.uk/search.aspx?query1=Vardill&rf=source:44

- webref6: http://etext.virginia.edu/bsuva/euromag/1EM.html

- webref7: http://www.fas.org/irp/ops/ci/docs/ci1/ch1c.htm

- webref8: http://www.war-art.com/british_infantry.htm

- webreb9: http://www.pos1.info/v/villonbal.htm

- webref10: http://gwpapers.virginia.edu/index/colonial/vlist.html

Fig1. Main locations associated with the Birtwhistle droving business 1745-1819

Figure2 Reconstruction of the field systems of Long Preston in the early 18th century

Figure 3 The Birtwhistles’ cotton mill at Gatehouse of Fleet c1800

Figure 4. The Birtwhistles of Skipton and Galloway

Figure 5. “Major Birtwhistle”; William Birtwhistle of Balmae and Skipton

Figure 6. The frontispiece to Anna Vardill’s book, possibly showing the young poet on the banks of the river Fleet at Gatehouse (from Axon, 1908)